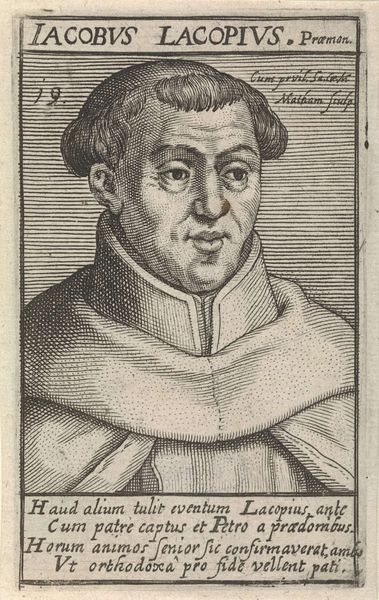

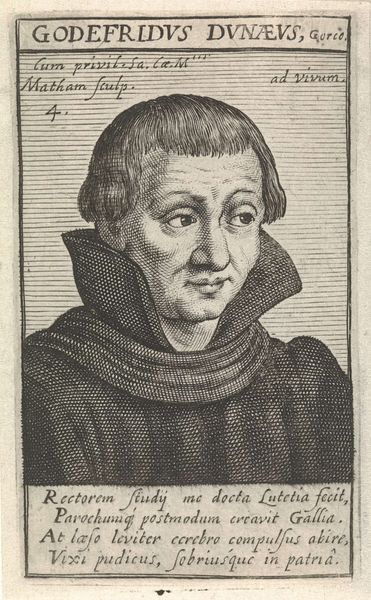

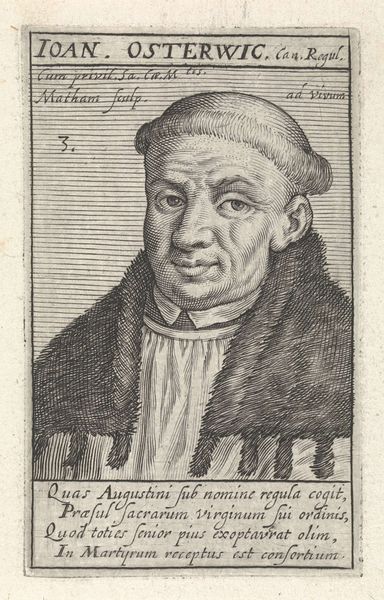

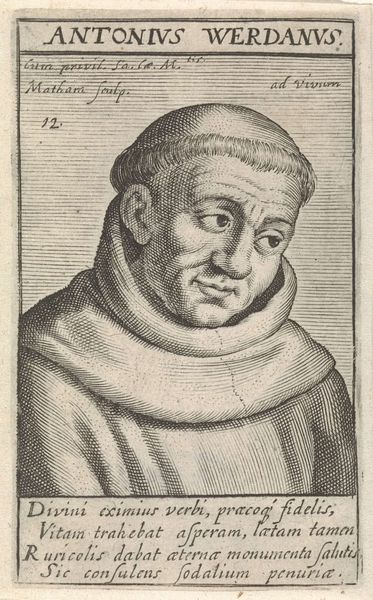

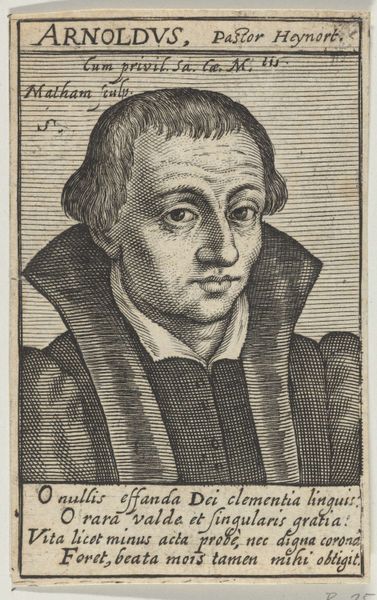

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a print, "Portret van H. Nicolaas Poppel," made by Jacob Matham around 1617 or 1618. It's quite detailed, even though it's a small engraving. I find it interesting that his profession, Pastor, is placed right at the top in Latin, above even his name. What stands out to you about this portrait in its historical context? Curator: The inclusion of "Pastor" directly above his name emphasizes Poppel's role in society. In the Dutch Golden Age, the church and its ministers held significant social and political sway, particularly given religious tensions between Catholics and Protestants. Note how Matham carefully inscribes "cum privil. Sa. Ca. Mt," signifying imperial privilege. It means this print had permission, protection even, to circulate freely under the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor. Without this privilege, distribution of such imagery was heavily monitored and subject to censorship. What might that indicate to us about religious freedoms during the period? Editor: It makes me think about how images themselves were political, and getting permission to distribute them was a whole thing. Also, I'm wondering about who the audience was meant to be for portraits like this. Was it just for family, or for wider circulation? Curator: Excellent questions. These prints functioned on multiple levels. They solidified social status, broadcast political affiliations, and contributed to a public persona. The verses at the bottom reinforce Poppel’s virtues. Prints were indeed distributed more widely than painted portraits, extending one's influence, like an early form of publicity. So this image tells us about Poppel’s status, but it also speaks volumes about the complex social and political networks operating during the Dutch Golden Age. Did you learn anything new looking at this image today? Editor: Definitely! I'm now much more aware of the power and social weight behind seemingly simple portraits from this time. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.