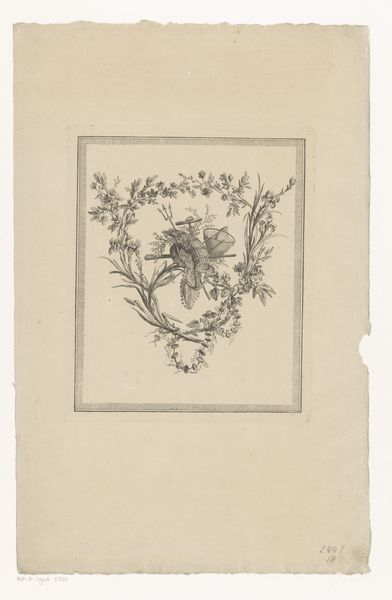

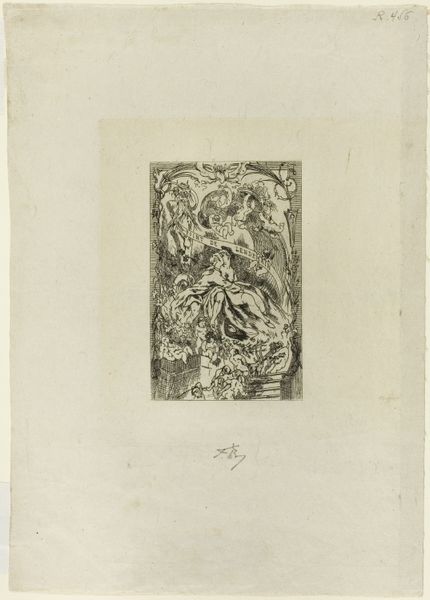

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 77 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Bloemstilleven", a still life of flowers created around 1870 by Vicomte Arthur-Jean Le Bailly d'Inghuem, using etching, ink, and paper. It feels almost…delicate, despite the darkness of the ink. What do you see in it? Curator: I see the visual embodiment of 19th-century bourgeois values subtly negotiating with a yearning for the natural world. The romantic floral arrangement, carefully composed and contained, speaks volumes about how nature was consumed and controlled in domestic spaces. Consider the print medium. Do you think the mass production enables greater access to art? Editor: Definitely! Making art affordable and widespread. Was there something subversive about choosing to represent nature instead of people at the time? Curator: Perhaps not subversive, but indicative. These domestic displays became symbolic performances of cultivated taste and status. Remember, this era saw intense industrial growth and urban expansion, which created this cultural yearning for the countryside and simpler times. Think of it as nature reinterpreted and packaged for the elite parlor. Notice the tight frame. Does that have an impact on your reading? Editor: It does box it in. Is it a critique of those values or just reflecting them? Curator: It is complicated. It simultaneously reflects and subtly questions them. Artworks like this help us consider the cultural work performed by images – how they mediate our relationship to the world. The political dimension in art comes not only through manifest statements, but through these subtler visual languages. Editor: That’s really fascinating! I'll never look at flower prints the same way. Curator: Me neither! Every object is encoded by the systems of values around its making and consumption.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.