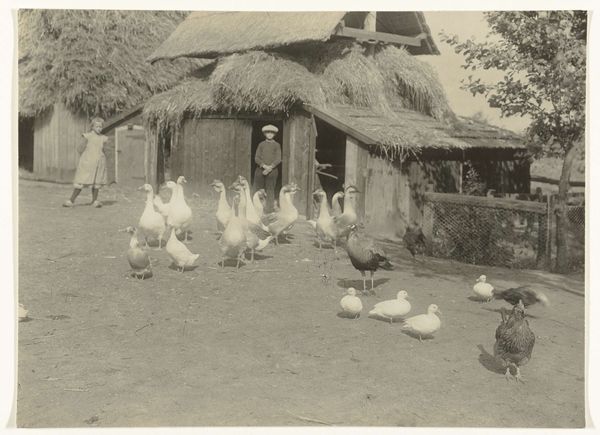

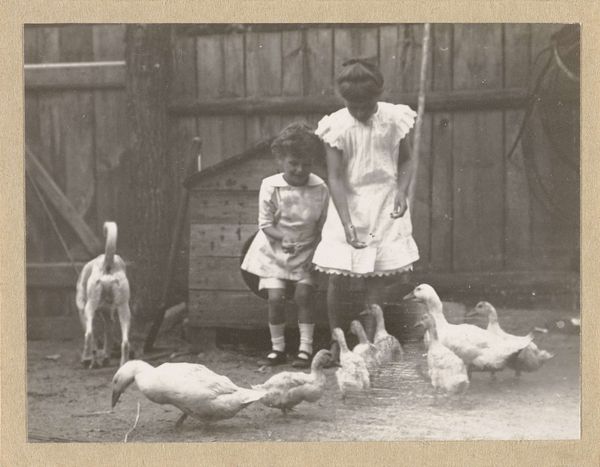

Erf van een boerderij, met ganzen, eenden en kinderen (dieren) c. 1900 - 1930

0:00

0:00

richardtepe

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this gelatin-silver print, "Erf van een boerderij, met ganzen, eenden en kinderen (dieren)" by Richard Tepe, was taken sometime between 1900 and 1930. There's a certain stillness to the scene, a quiet observation of rural life. What strikes you most about this photograph? Curator: I see a staged scene attempting to portray a natural order that’s invariably imbued with human agency. It provokes thoughts about land ownership and labor. Who are these children and who owns this land? Tepe’s lens subtly reveals how idyllic scenes can mask social stratifications, reflecting power dynamics inherent in land ownership and agricultural labor. Have you considered this interplay of staged versus natural in light of class differences? Editor: I hadn’t really thought about it like that. The image felt almost timeless to me, a snapshot of a simpler existence. But what you're saying is that it's not really capturing reality, but maybe shaping a narrative around it. Curator: Exactly. Consider the children posed at the door, in contrast to the ducks freely moving. This positioning can speak to social expectations and limited possibilities imposed based on class and perhaps even gender in that era. Can we consider this staging as a form of control? What possibilities could lie in interpreting Tepe’s images from a feminist or postcolonial perspective, given the Netherlands' colonial past and the likely societal constraints placed on women and marginalized communities? Editor: It’s a lot to think about. I initially saw it as a charming, almost naive depiction of farm life. Curator: That initial charm is precisely what makes it effective. It draws us in, and then we can begin to question the underlying assumptions about rural life, work, and the way these are often idealized. This highlights how art can engage in social critique, even through seemingly gentle representations. Editor: I’ll definitely look at images of this era differently from now on. Thanks for sharing your perspective. Curator: My pleasure! Questioning is what art history should inspire us to do!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.