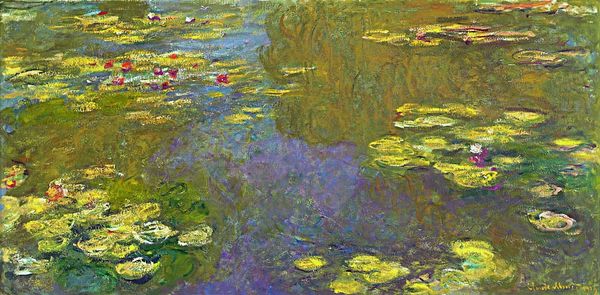

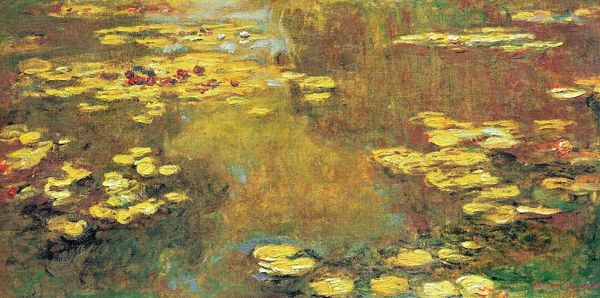

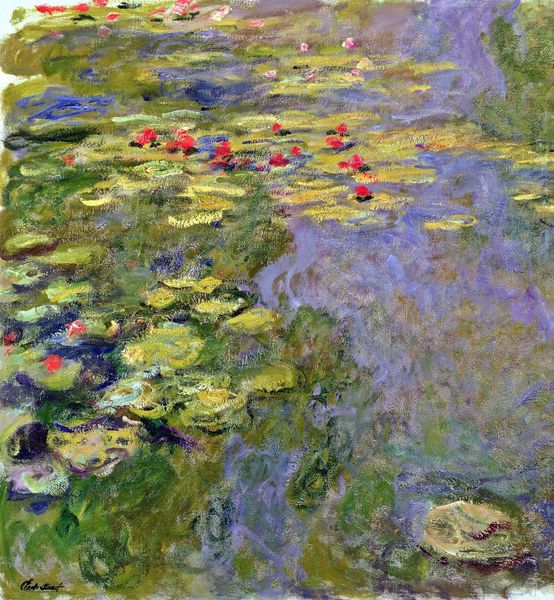

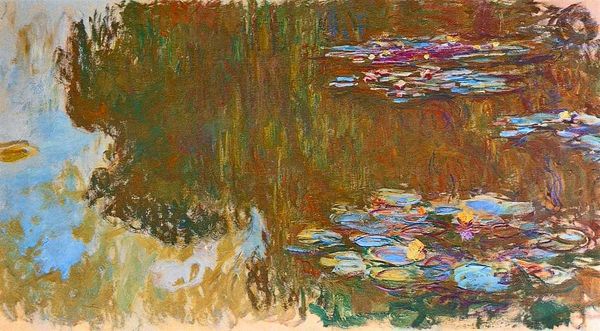

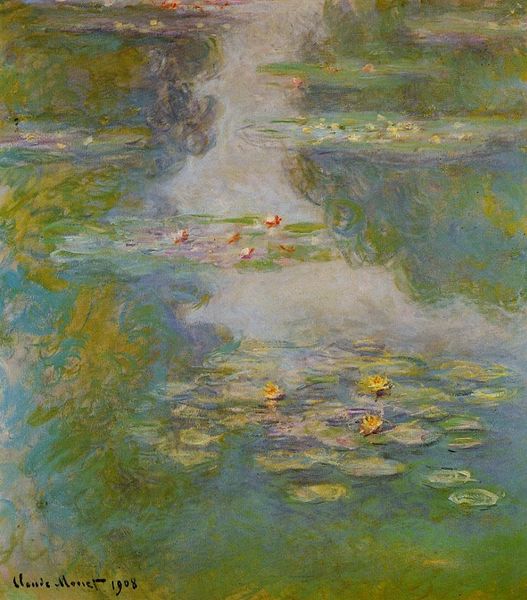

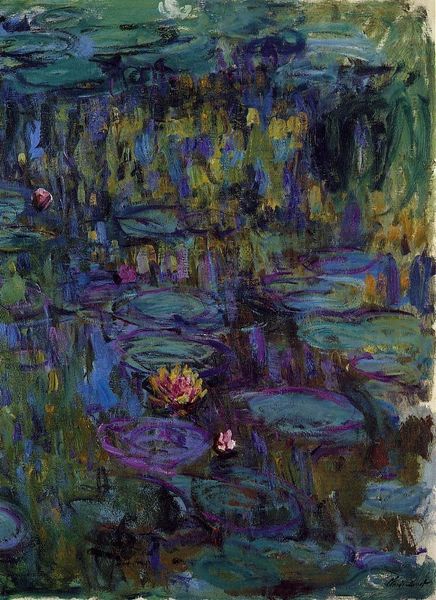

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: I'm immediately struck by the heavy impasto. You can almost feel the weight of the oil paint itself. Editor: Indeed. This is Monet's "Water Lilies," painted around 1917, a powerful piece capturing the essence of his garden at Giverny through a mature, almost abstract impressionistic lens. It begs consideration of his place within the changing world of post WWI Europe. Curator: I agree about abstraction—the lily pads become flattened planes of colour, nearly divorced from their natural form. It pushes the limits of representation and the craft. The viewer confronts paint, materiality itself. Editor: But those lilies weren't mere aesthetic fodder; remember Monet's failing eyesight at this time, exacerbated by wartime hardships. He painted these lilies in defiance of that adversity. Curator: Absolutely. These paintings—painted en plein air—are, in essence, records of a sustained, physical engagement with his environment. His laborious working process and consumption of materials speaks of something. Editor: It also prompts us to confront historical questions: consider the social, cultural conditions shaping not only artistic practice but also reception. Did the public perceive defiance in the face of conflict within these tranquil depictions? Curator: Or perhaps this series offered some much-needed, idyllic refuge amid turmoil, achieved via the intensive work of rendering fleeting atmospheric impressions, yet so substantial as pigment. Editor: Regardless of intention, it's undeniable that Monet's "Water Lilies" functions on several levels. I leave feeling as though art making at scale offers solace during uncertain times. Curator: Agreed, by drawing us in so immersively, we may not only find an echo of what it was to be Claude Monet laboring in Giverny, but how human endeavour survives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.