Dimensions: height 440 mm, width 348 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

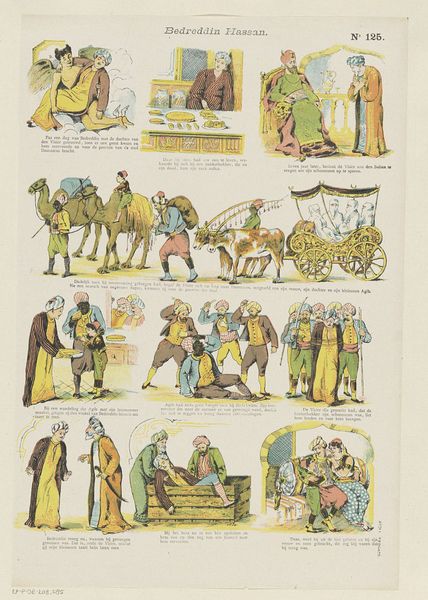

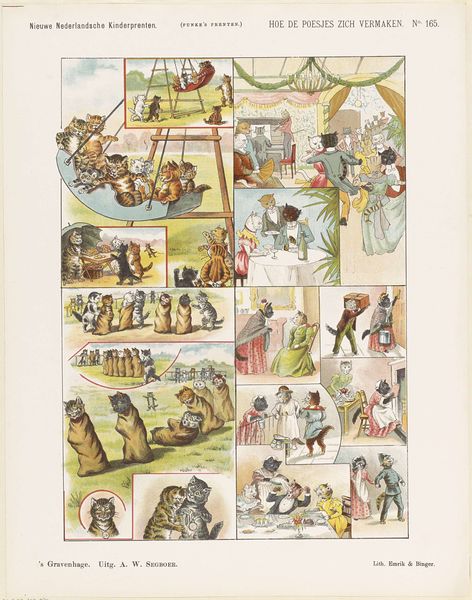

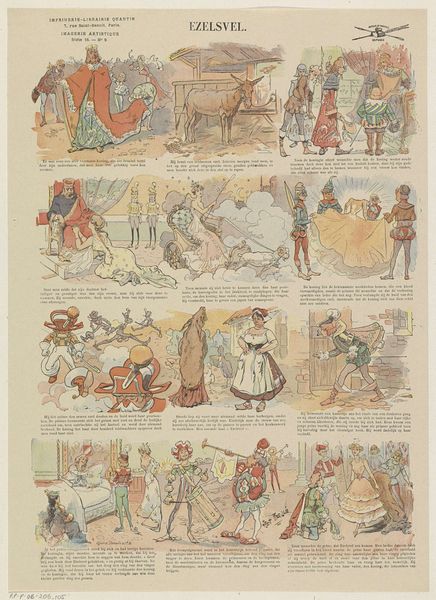

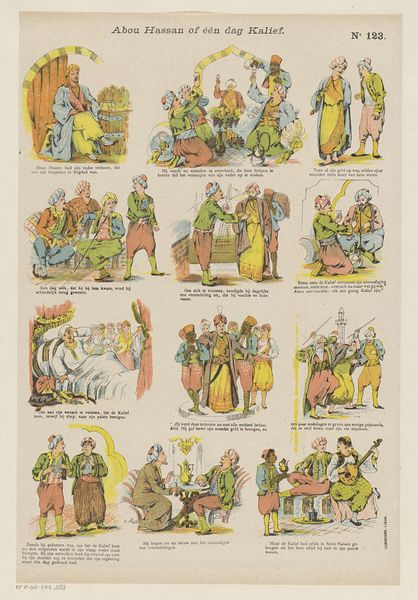

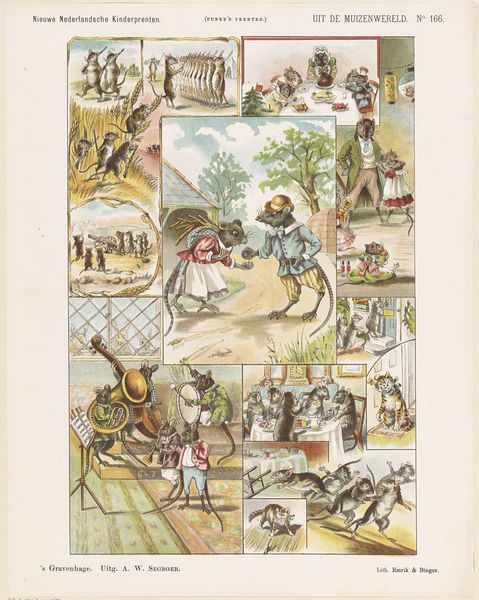

Curator: Well, here we have "Vreemde Volken (II)", a lithograph print by Arie Willem Segboer, created sometime between 1903 and 1919. What strikes you about it? Editor: My first thought? A rather idyllic and sanitized view of the world, doesn’t it feel a little like a stage set? Each panel feels meticulously placed and disconnected, as if curated for… consumption? Curator: Absolutely! It’s clearly steeped in orientalism, that late 19th and early 20th-century fascination and romanticization of the "East". This piece reflects that worldview – a collection of stereotypes presented as objective reality. Editor: The "genre-painting" tag also rings true. It’s a picture of “everyday” life...but whose everyday? And for what purpose? It feels… educational in a very problematic way. The lithography, with its vivid color palette, makes these "exotic" scenes inviting, but…is that deceptive? Curator: Segboer's reliance on ukiyo-e influences is quite noticeable. Look at the figures, the flatness of the images, and how space is represented. These choices romanticize, rather than represent faithfully. It begs the question of intention, doesn't it? What purpose did it serve at the time? Editor: And even now, it still perpetuates these narratives. We, as viewers, need to actively question what we’re seeing, what biases are being reinforced. It’s not just a historical piece; it’s a conversation starter. The artist is attempting to illustrate cultures other than his own, what would those individuals feel about how they are depicted in these prints? Curator: That’s the power of art, isn’t it? To provoke thought, even when that thought leads to discomfort. This lithograph, in all its problematic beauty, can teach us volumes about the dangers of misrepresentation and the importance of cultural sensitivity. Editor: Indeed. It highlights how crucial it is to critically examine historical narratives and challenge preconceived notions of the "Other," especially when these narratives continue to echo in contemporary society. It encourages us to consider who creates the images and who benefits from their circulation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.