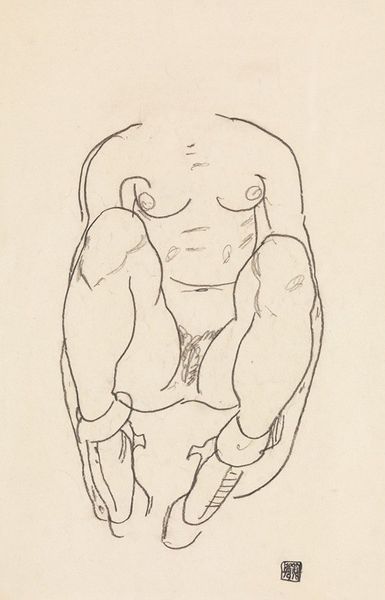

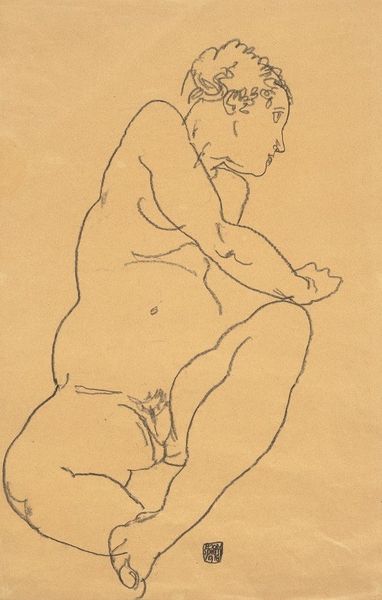

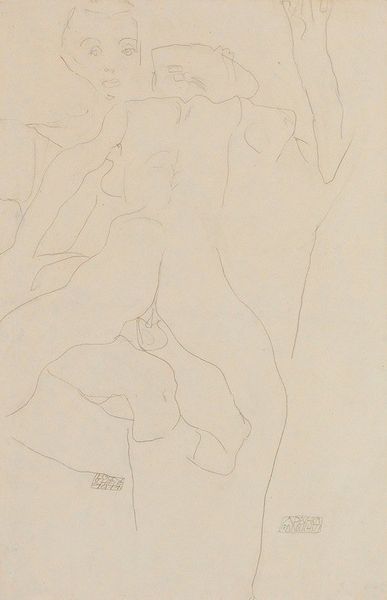

drawing, dry-media, pencil

#

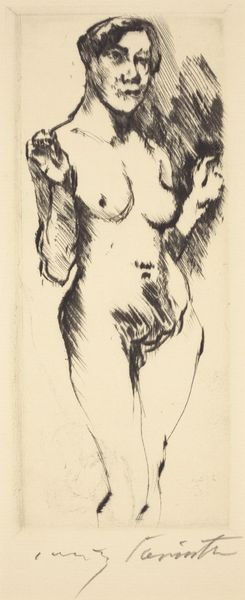

portrait

#

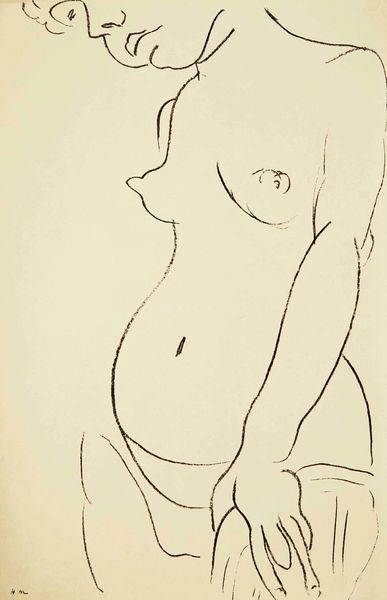

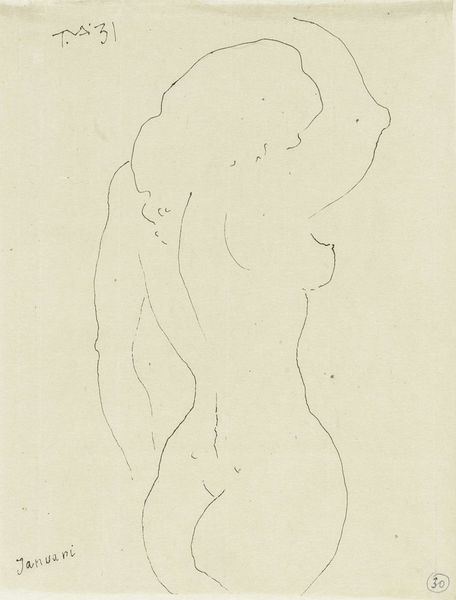

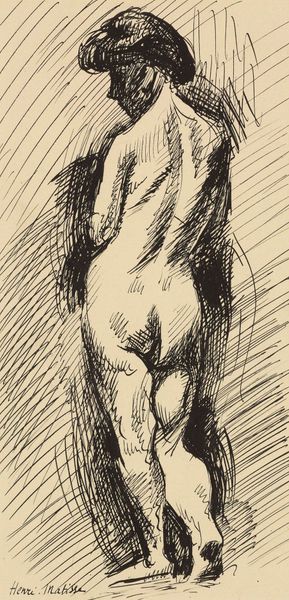

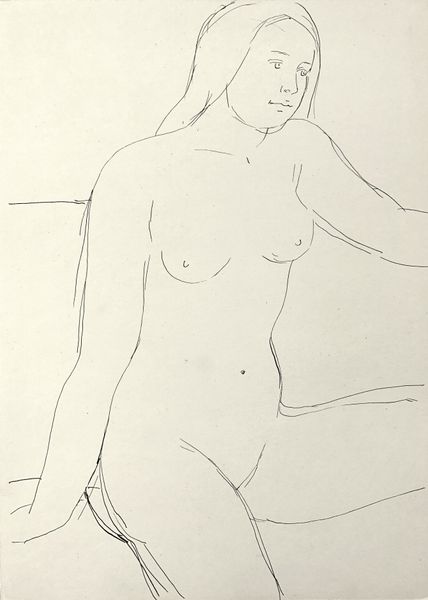

drawing

#

landscape

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

dry-media

#

female-nude

#

pencil

#

expressionism

#

nude

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

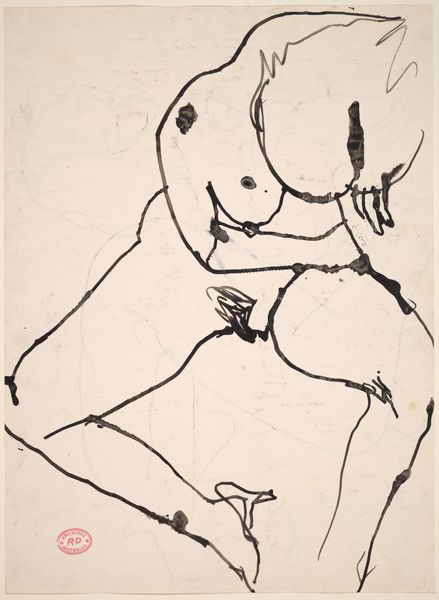

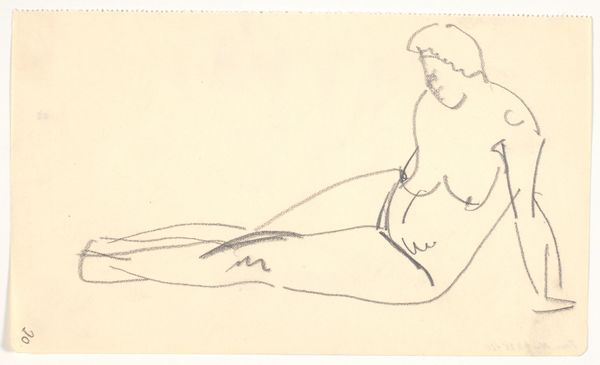

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have Paula Modersohn-Becker’s drawing "Female nude on the grass." It’s executed in pencil on paper, a study in the tradition of the nude figure set against, as the title suggests, a landscape. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the vulnerability of the figure, and the density of the hatching surrounding it. There’s almost a feeling of being trapped. Curator: Modersohn-Becker’s process was rooted in a direct engagement with the materials. The visible strokes of the pencil suggest a rapid, almost urgent attempt to capture the essence of the body, a raw exploration of form and volume, which links to the emergence of expressionism in Germany. Think about the price of paper at that time. How the act of simply obtaining art supplies represented significant planning and resources for a woman artist in the early 20th century. Editor: Absolutely, the drawing exists within a context of institutional constraints, particularly considering societal views on female artists and the nude at the turn of the century. Did that affect how these types of drawings were viewed? How often were they exhibited in a public context, and how did that exposure impact the artist’s reputation? Curator: Precisely. Her contemporaries, and art critics of the time, were highly critical of such expressions in figuration. They looked at such works with much less openness. One can read it now as being a commentary on objectification, particularly how the female body was framed, both within and outside the institution. But how do you see it being publicly presented, or considered outside of art production and markets? Editor: The history of representing female nudes has a really long lineage of predominantly male gaze, think of paintings or photographic practices and you’d think that the artwork can provide a counter-narrative that contests that traditional representation and that is precisely what has brought forward new feminist discourses around female artists who reclaim agency over the visual depiction of women's bodies. But even if the art tries to address power, one might also ask ourselves "does it work if most people can't see it in the first place?" Curator: And this question of public accessibility speaks volumes about the enduring struggles surrounding gender representation and labor rights, I believe. What materials were made easily available, and what bodies were shown in institutional context are not separate from another. Editor: I agree. Thank you for guiding us to think a bit beyond what’s readily shown, towards who decides these standards to begin with. Curator: Thank you, that was insightful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.