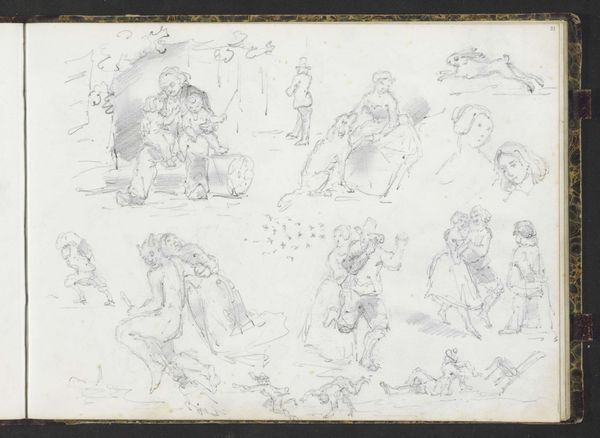

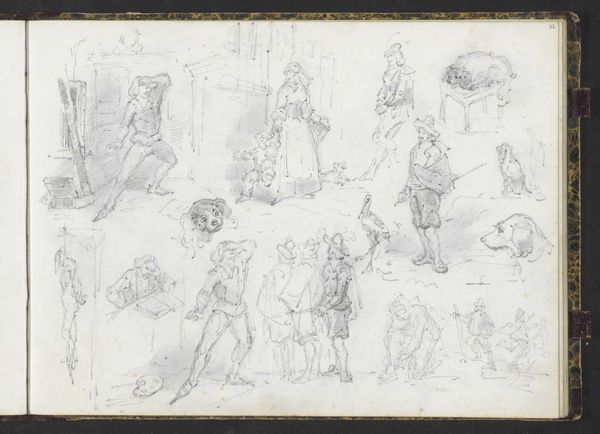

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

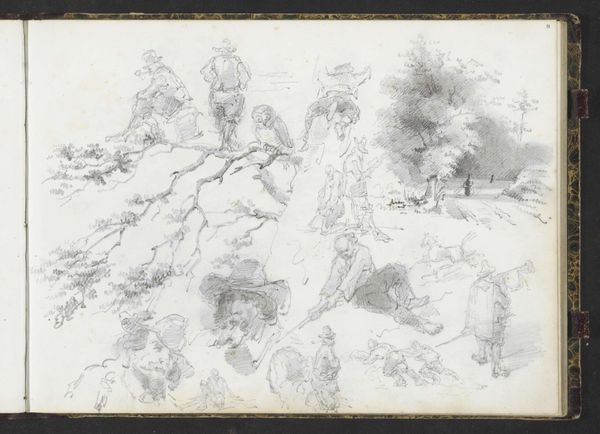

landscape

#

paper

#

pencil

#

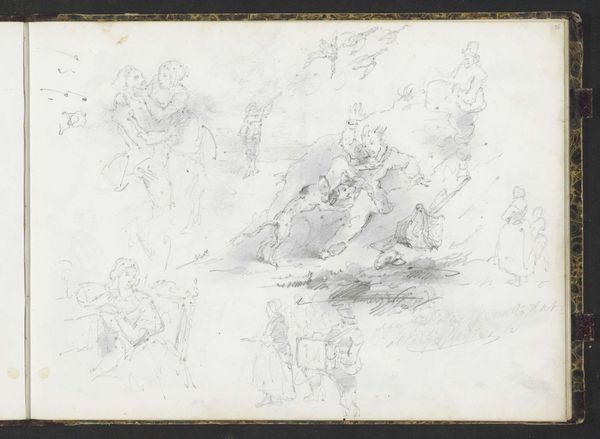

history-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

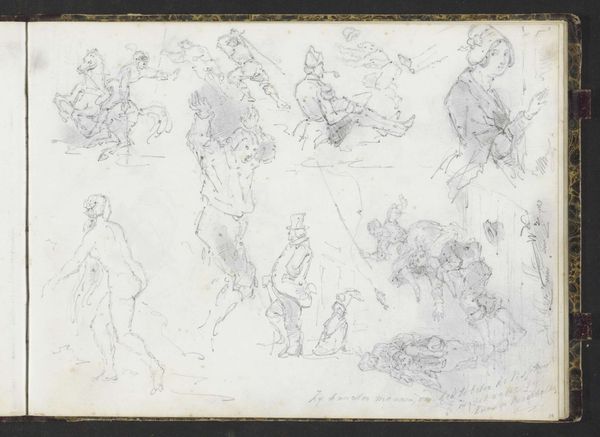

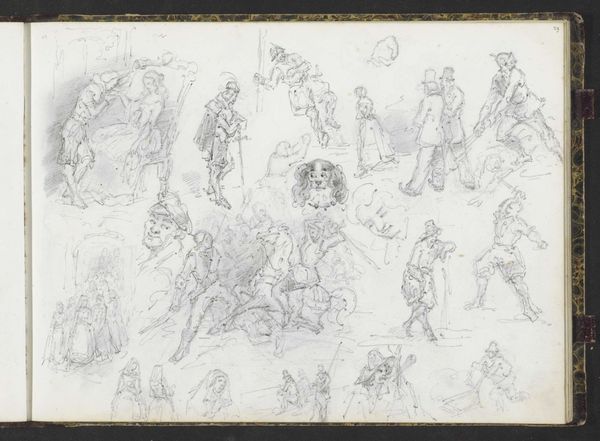

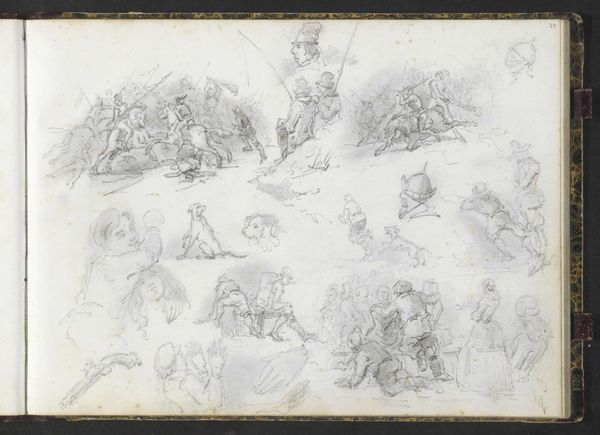

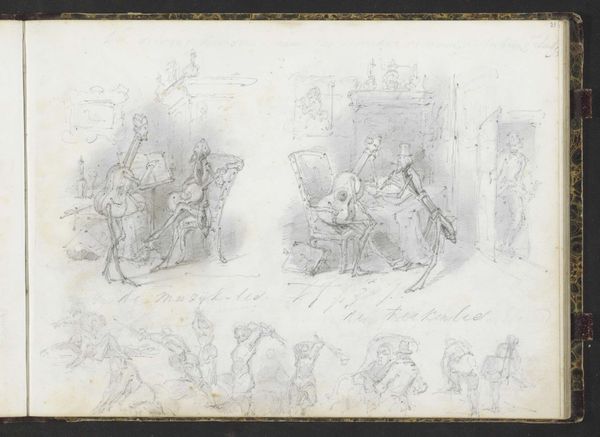

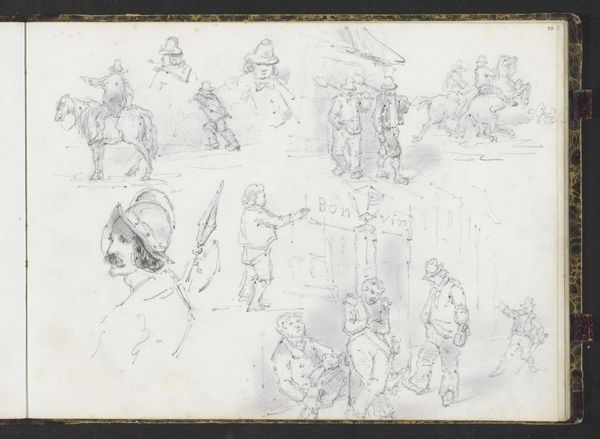

Curator: Let’s discuss this sketch, "Studieblad met ruitergevechten en een boom," which translates to "Study Sheet with Cavalry Battles and a Tree" by Lambertus Lingeman. We estimate it was made sometime between 1839 and 1894, employing pencil on paper. What strikes you immediately? Editor: There's a captivating urgency here, even in its sketch-like form. The battles scenes especially; they're rendered with a frantic energy that communicates a certain…violence, despite being depicted in light pencil strokes. Curator: The immediacy you feel reflects its purpose – a study, not a finished piece. Consider how history paintings of the era often glorified warfare, sometimes obscuring the grim realities. I wonder, looking at this from today's vantage, how it invites us to unpack such glorification? How are notions of heroism and nationhood implicated here? Editor: Precisely. And given the period, we need to view this within a historical framework of empire building and colonial conflict. Lingeman was operating within specific institutional settings; how did these socio-political forces influence what was deemed worthy of artistic attention, even in study form? Who was expected to view it, and with what perspective? Curator: A fascinating point. The relatively humble medium, pencil on paper, counters any potential grandiosity. These sketches perhaps served as preparatory investigations – experiments in composition, movement, and the portrayal of martial subjects. But to whose end? Was Lingeman producing imagery designed to perpetuate or question existing hierarchies? Editor: Furthermore, let's not ignore the lone tree on the page. Its isolation draws attention. Could this serve as commentary—a contrast between the supposed glory of combat and the quiet endurance of nature, a sort of anti-war statement embedded within a martial theme? Curator: The tree could also be an assertion of Dutch identity bound to ideas of landscape—a persistent construction throughout the period that we can decode through this little drawing, perhaps? Thank you for illuminating our perspective with yours. Editor: My pleasure, thinking about how the politics of representation and reception inevitably affect historical artwork is so important.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.