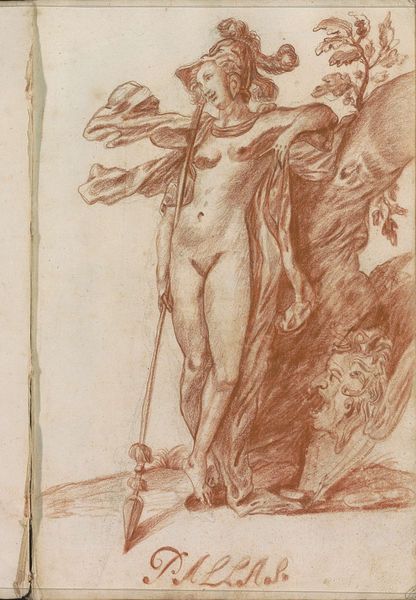

Dimensions: height 257 mm, width 150 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We are standing before "Hermaphroditus as Caryatid," a pencil drawing created by Giulio Romano circa 1510-1521. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: The figure feels... unfinished. The pose is so theatrical, almost defiant, yet rendered with delicate pencil lines that seem to soften the androgyny. It evokes a strange mix of power and vulnerability. Curator: Precisely. Romano was a master of Mannerism. Notice how the elongated proportions and contorted pose distort classical ideals of beauty. The figure, based on the mythological Hermaphroditus, son of Hermes and Aphrodite, is not simply standing, but seems to strain under the weight it ostensibly supports. This violates the traditional understanding of a caryatid as both structural and idealized. Editor: The ambiguity of the figure's gender immediately struck me. Hermaphroditus embodies a transgression of binary gender roles, reflecting the societal tensions and anxieties of the time. By placing this figure in the architectural role typically assigned to female figures, Romano is challenging classical ideas. But I'm troubled, given its historical context; is this progressive, or merely a fetishized representation that ultimately reinforces power imbalances? Curator: A provocative question. Structurally, the artist uses hatching to create volume, but he also leaves many areas of the paper untouched, emphasizing line and form over realistic modeling. It’s not meant to be purely representational. He seems to play with surface and depth, using only tonal contrast for emphasis. The draping fabric is sketched lightly, giving the impression of movement frozen in time. Editor: Right. The fabric hints at a certain concealment. But given our historical distance, how can we ensure we’re not imposing contemporary ideals onto a piece made in a radically different culture? We need to also address our current trans and gender-nonconforming audiences who might view this imagery differently than scholars. What does it mean for them, and how does the museum become a safe space for these important dialogues? Curator: Museums do evolve. I see how my traditional assessment may need a broader lens. Editor: Exactly. So how does the museum, in its architecture and its collection, reflect the evolving ideas about identity? Curator: The figure itself refuses any one easy classification, which speaks volumes about fluidity and the constructed nature of all such definitions. A challenging, dynamic artwork. Editor: Indeed, and a challenging, dynamic responsibility for us as interpreters.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.