drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

quirky sketch

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

caricature

#

sketch book

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

initial sketch

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

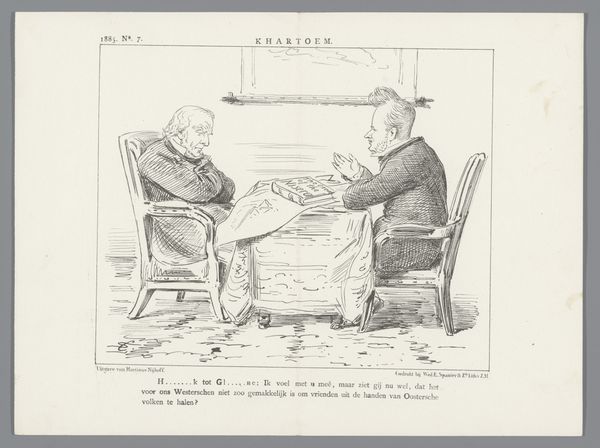

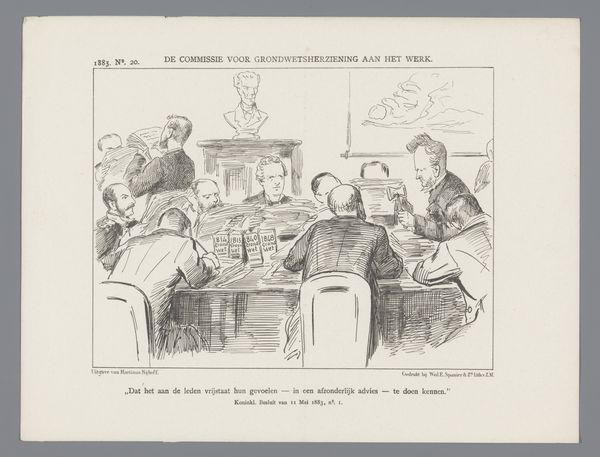

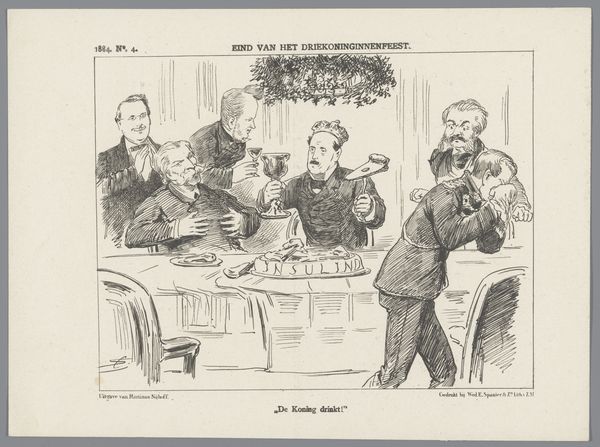

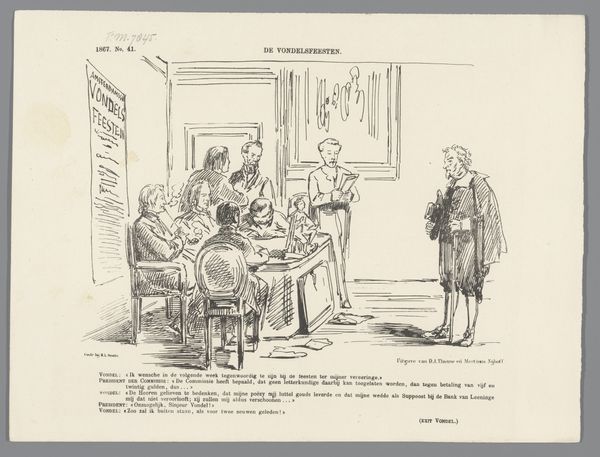

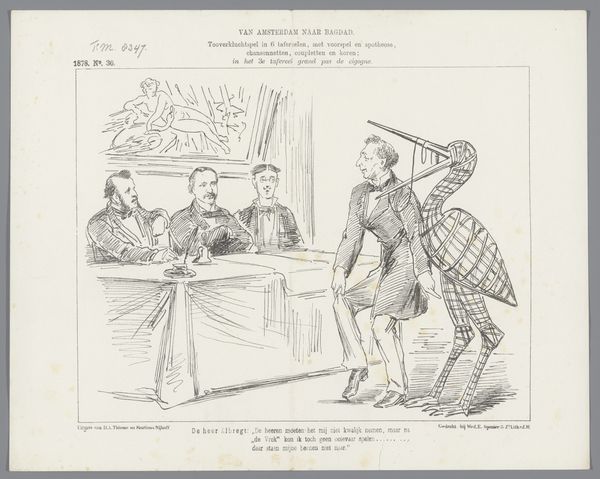

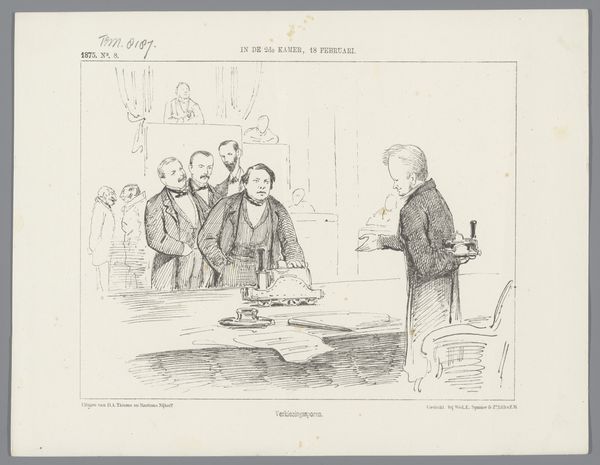

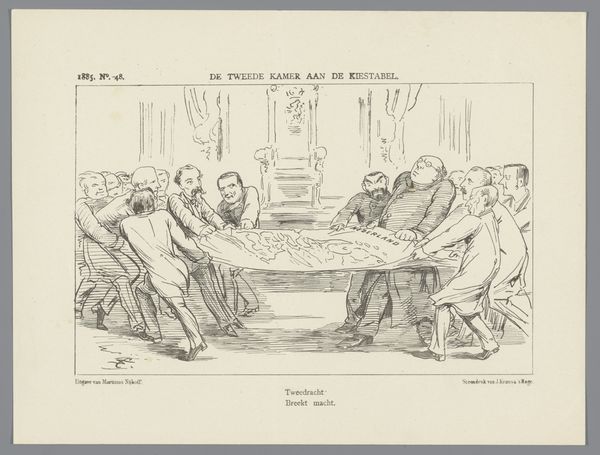

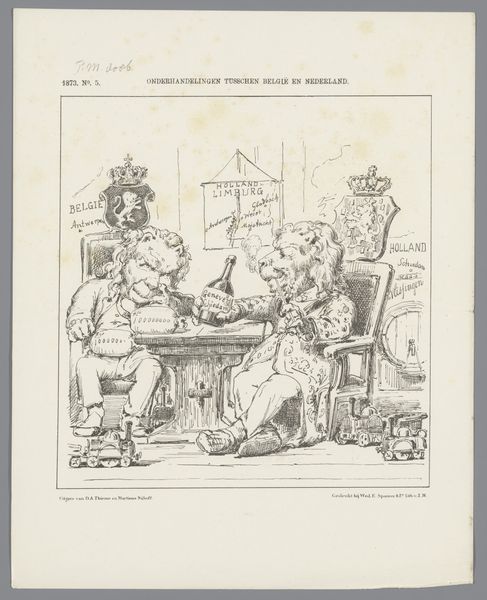

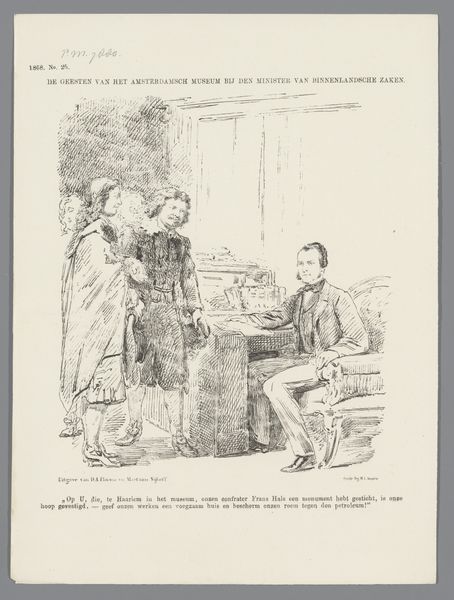

Curator: Here we have an intriguing engraving, “‘s Gravenhage in Juny 1853,” created by Carel Christiaan Antony Last. It resides in the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: My first impression is that it's delightfully absurd. There's this rather stark, almost austere quality to the engraving itself, but the scene… it’s quite humorous. I find the exaggerated lines and the almost caricature-like quality immediately striking. It reminds me a little of Honoré Daumier's satirical lithographs. Curator: The exaggerated features immediately point to caricature, a favored approach for commenting on society. Consider that both figures are clearly delineated to reflect certain social and political standpoints during the period it represents. I see the weight of leadership. Editor: Absolutely, there's definitely social commentary bubbling under the surface. I find the heavy lines in the men's clothing contrast against the stark simplicity of the backdrop and setting a very economic commentary on their relationship to labor and industrial production. Everything down to the detail of the engraved mark feels deliberately functional. Curator: Indeed. Consider, too, the symbols here. The text, while initially distracting, gives us some clear clues. But I am drawn, of course, to the oversized crown dominating the table. Is it symbolic of a peace accord, a proposed consolidation, or something far more complex? The placement—between the two figures but unclaimed—infuses this rather basic scene with multiple meanings. The composition places this piece right in the center of this power struggle, highlighting cultural tension and ambition in ways both cutting and playful. Editor: This engraving style lends itself so well to disseminating political ideas widely through affordable means of reproduction, making potentially seditious ideas accessible to a broader population than painting ever could. So here's Last, in 1853, making not just a picture but an argument with these simple strokes of metal on paper, challenging existing social structures by creating something everyone can access. Curator: It’s remarkable how many narratives an image can carry. The work’s continued relevance showcases how lasting, even subconscious, some archetypes can remain. Editor: In the end, we are left with questions on power and negotiation – something even the humblest medium can stir with incredible sophistication.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.