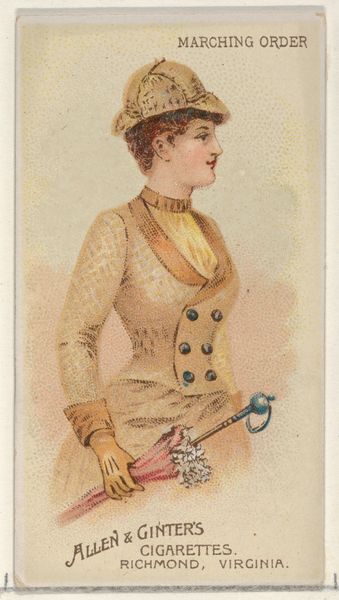

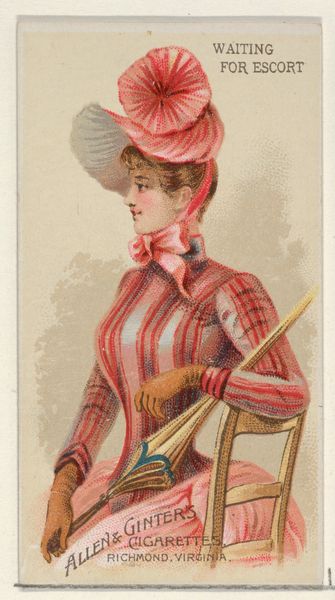

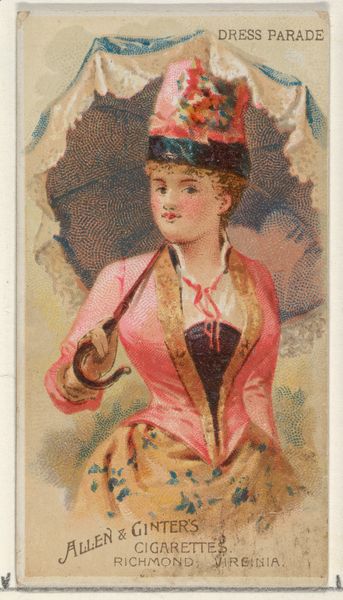

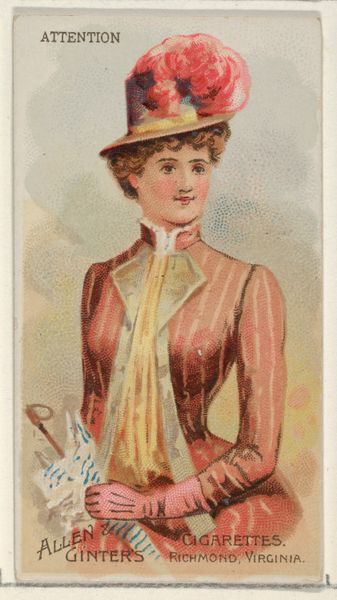

Halt, from the Parasol Drills series (N18) for Allen & Ginter Cigarettes Brands 1888

0:00

0:00

#

portrait

# print

#

caricature

#

coloured pencil

#

19th century

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 3/4 x 1 1/2 in. (7 x 3.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: What a peculiar little image. Editor: Yes, isn't it? The immediate feeling is almost…clinical. Detached. It's striking how much detail is packed into such a small frame. Curator: Indeed. What we're looking at is one of the cards from Allen & Ginter's "Parasol Drills" series of cigarette cards, specifically N18, entitled "Halt". They were produced in 1888, right at the height of cigarette card mania. Editor: Ah, a clue! Halt is such a definitive word. I notice her tightly gloved hands clenching the eponymous parasol, the somewhat stern expression... It feels performative, even constricting, like a woman bound by ritual. Curator: Exactly! Think about the late 19th century, the societal constraints on women, even within acts as simple as leisure. The parasol itself becomes a symbol of that restriction and supposed respectability. The cards often played into Orientalist fantasies, echoing the Western gaze upon appropriated cultural practices and imbuing these exotic images with Western consumerist desire. Editor: It's amazing to see the symbolic weight placed upon something as seemingly innocent as a parasol drill. Tell me, does this intersect at all with Japonisme that the notes mention? Curator: Absolutely. You see the fascination with precise movements, and the slight stylization that resembles some woodblock prints of the period. Allen & Ginter certainly adopted aspects of that visual language. But in doing so, they're commodifying it, packaging it for mass consumption along with tobacco, erasing the deeper cultural significance in exchange for aesthetic appeal and ultimately for profit. Editor: A capitalist reduction. Interesting! That changes my initial reading of clinical detachment into more a form of enforced social choreography, I think. It’s the commercialization of identity—her identity, our perceptions of her—on the front of a cigarette packet. Curator: Precisely. It challenges us to unpack what seemingly benign imagery conceals about gender, cultural appropriation, and capitalist exploitation in 19th-century consumer culture. Editor: It goes to show how even the most apparently trivial objects are, in fact, deeply embedded within larger socio-political and cultural contexts. And the cigarette card acts as an uncomfortable, pocket-sized reminder of these processes at play.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.