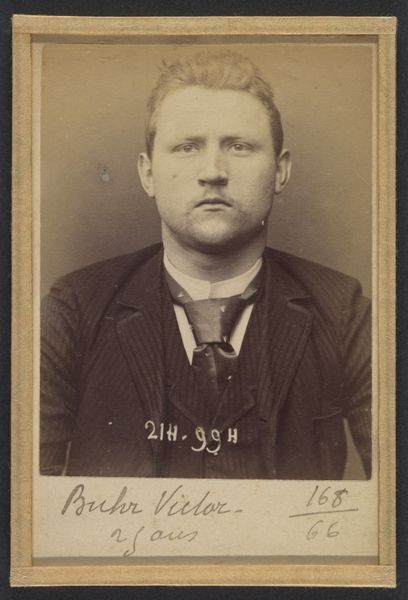

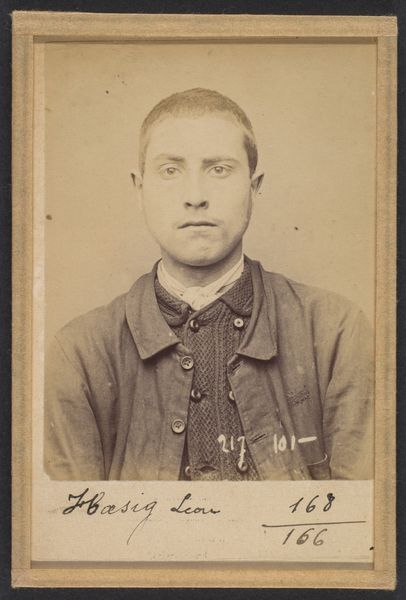

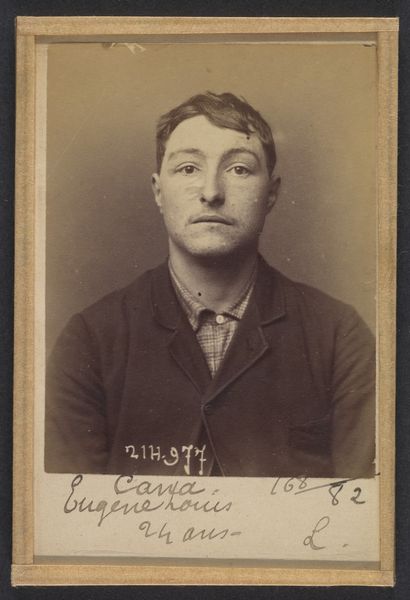

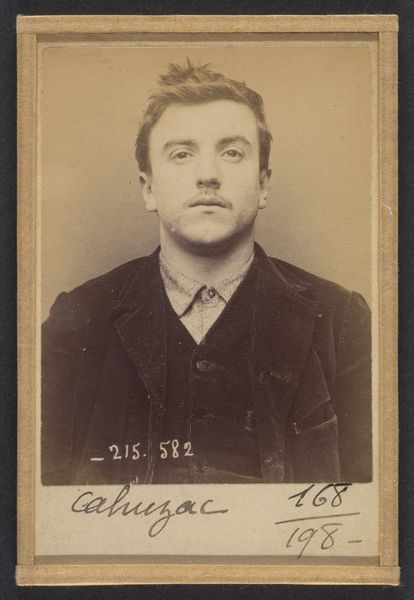

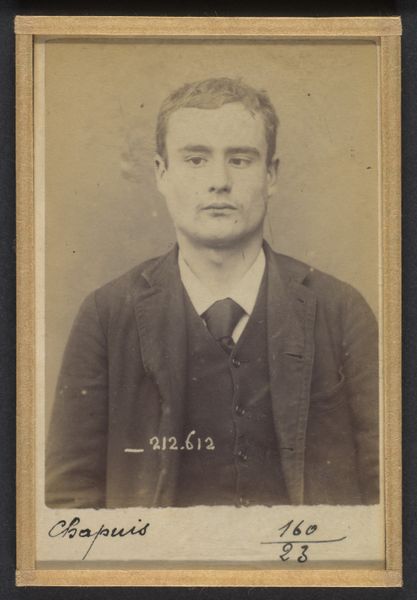

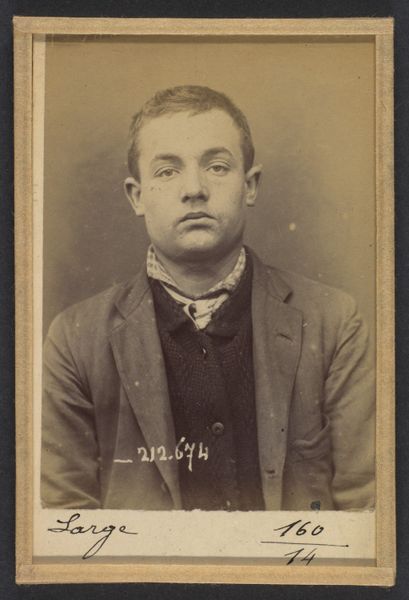

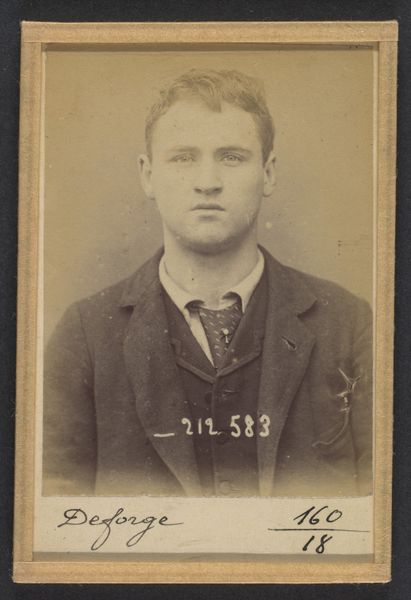

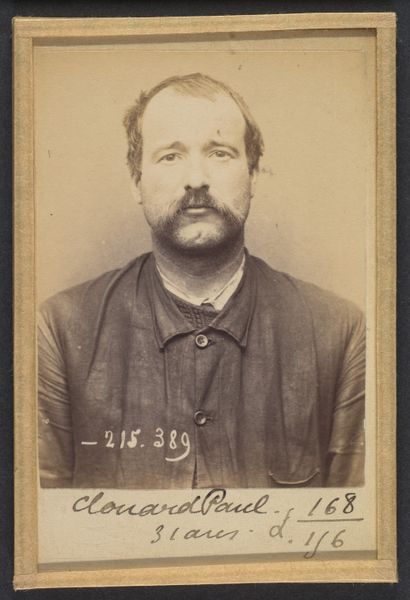

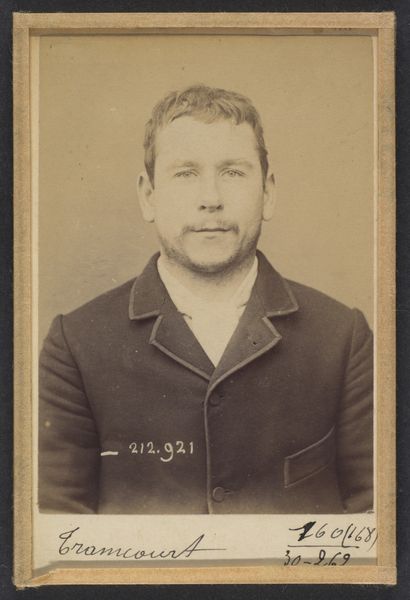

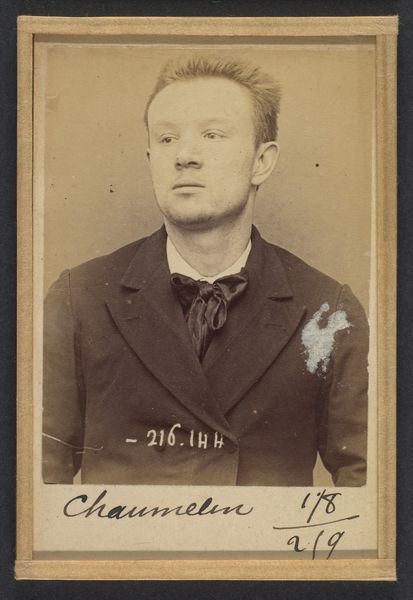

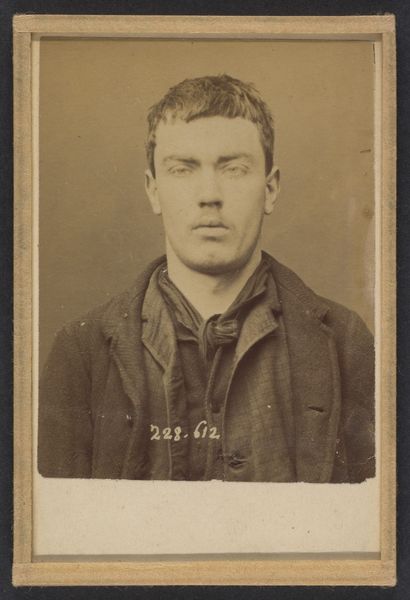

310. Olivier. Philippe, Octave. 25 ans, né le 29/6/68 à Paris XVIIle. Plombier. Anarchiste. 16/3/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

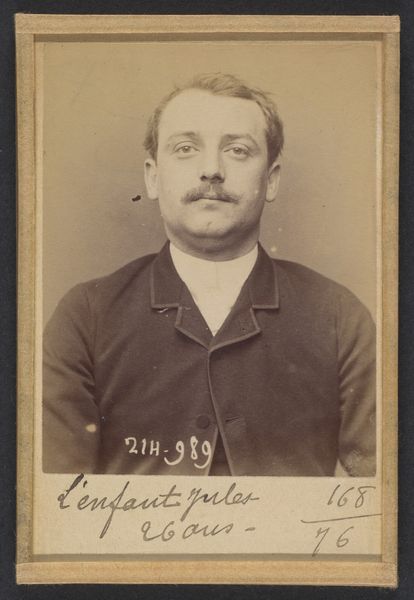

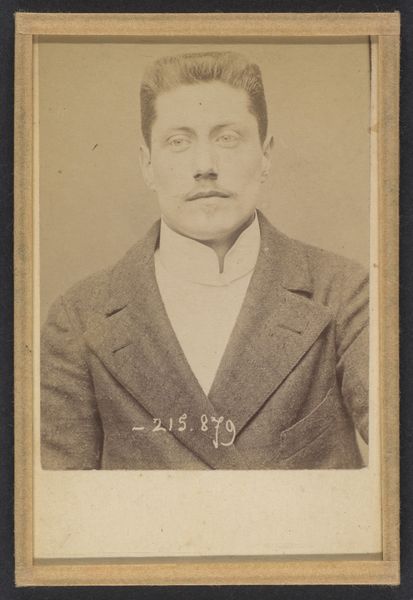

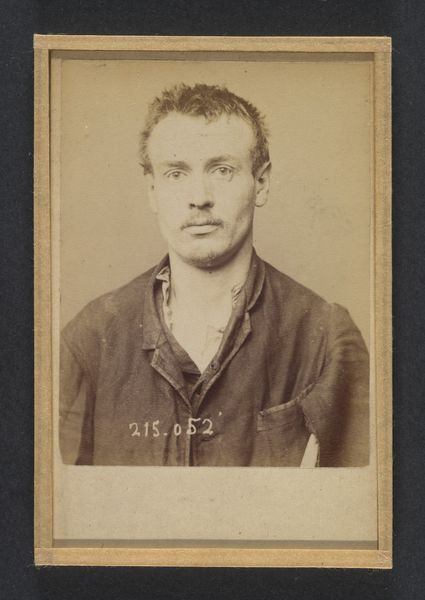

Curator: Standing before us is an albumen silver print produced in 1894 by Alphonse Bertillon. Its full title is quite a mouthful: "310. Olivier. Philippe, Octave. 25 ans, né le 29/6/68 à Paris XVIIle. Plombier. Anarchiste. 16/3/94." It's currently part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My initial impression is of bleakness – a sort of industrial-era resignation seems etched on the subject’s face. Editor: My immediate response is discomfort. It’s impossible to ignore the clinical nature, this dispassionate stare directly confronting the viewer, forcing us to question our own positions relative to power and systems of control. Curator: Absolutely. Bertillon's work centered on photographic and anthropometric identification for the French police. This particular image exemplifies his systematic approach, combining physical measurements with visual records—a kind of early forensic craft, if you will. You see, there’s careful documentation visible, measurements written right onto the image, essentially turning the man into a set of data points. Editor: Yes, and this photo encapsulates a period rife with anxieties about social upheaval. This portrait’s subject, clearly identified as an anarchist, links directly to the era’s fears of dissent, labor movements, and the perceived threat to social order. Consider what it meant to brand someone "anarchist" at the time; it stripped individuals of their complexities. The very materials and techniques of photography were co-opted as tools for state surveillance and control. Curator: Exactly! And the gelatin-silver printing process, while capable of capturing incredible detail, also lent itself to mass production of these identification cards. Bertillon created a material system. The repetitive nature, the standardization of the mugshot... These photographs become both records of a person, and indictments by association, crafted through a network of labor and material resources. Editor: The seemingly mundane surface—the gelatin-silver print—becomes a charged artifact, pregnant with socio-political context. We’re left to reckon with questions of personhood, resistance, and the pervasive nature of institutional power, even today. Curator: I’d add that considering Bertillon’s context helps us examine how artistic materials get caught up in structures of power, fundamentally changing the meaning of “making.” Editor: This portrait is a stark reminder that the creation and consumption of images are never neutral acts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.