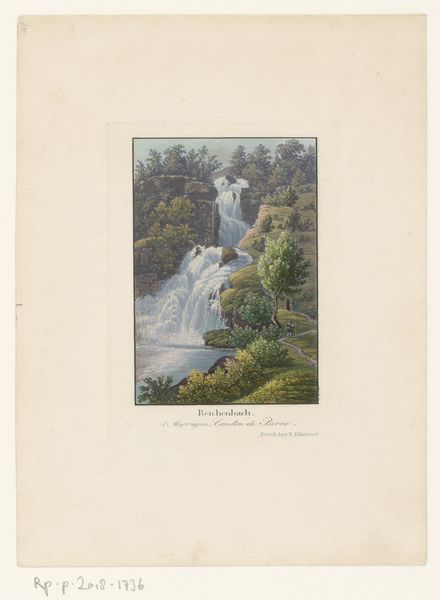

The Laughing Waters Three Miles Below the Falls of St. Anthony 1849 - 1855

0:00

0:00

painting

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

indigenous-americas

Dimensions: 7 3/4 × 6 in. (19.7 × 15.2 cm) (image)12 3/4 × 9 5/8 in. (32.4 × 24.4 cm) (sheet)21 1/2 × 17 9/16 × 1 1/8 in. (54.6 × 44.6 × 2.9 cm) (outer frame)

Copyright: Public Domain

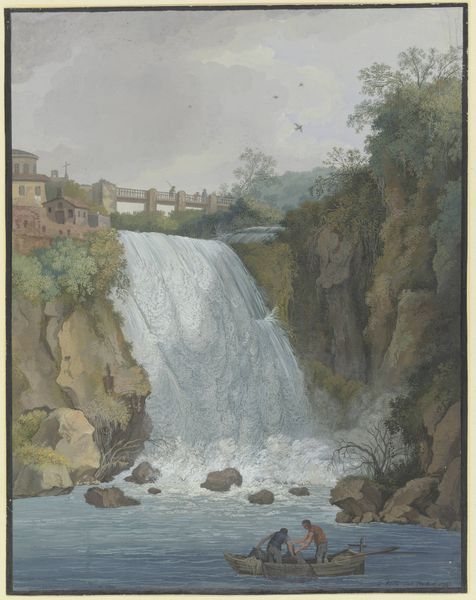

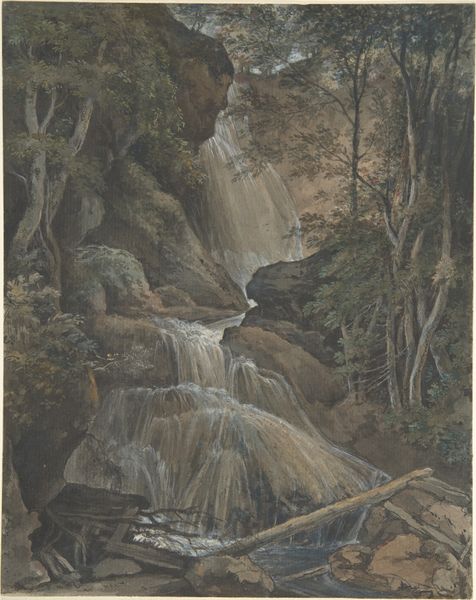

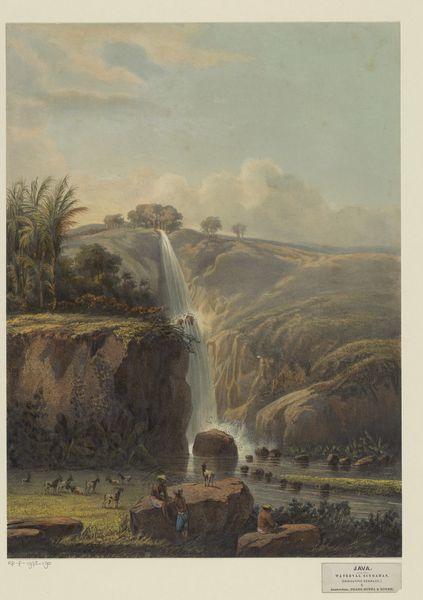

Curator: Seth Eastman’s watercolor, "The Laughing Waters Three Miles Below the Falls of St. Anthony," painted between 1849 and 1855, captures a fleeting moment of life near a powerful waterfall. It's a really interesting mix of observation and perhaps… a touch of something else. Editor: My first impression is… well, idyllic, almost deceptively so. The light, airy washes of color and the little vignettes – a hunter, a leaping deer – they soften what I imagine must have been a pretty overwhelming landscape. Curator: I think you hit on something there. Eastman, who was also a military officer, had unique access and a mandate to document Indigenous life. What we see, I believe, is nature perceived through that specific historical lens. Editor: Yes, the strategic act of framing nature itself. The waterfall becomes a romantic backdrop for the figure of the Native American hunter – his presence staged within a larger narrative of the "untamed" wilderness, as if placed there for a painting, forever pursuing. Curator: Absolutely, and consider the scale. That single figure drawing his bow at the cliff’s edge becomes the fulcrum point of wilderness versus civilization, rendered by very deliberate brushstrokes. Look at the loose flow in rendering that vigorous falls and compare with that solitary archer and bounding deer. It’s a story of conquest, maybe a subtle form of visual rhetoric of Manifest Destiny? Editor: The tension is in the romanticization of nature and also the potential for conflict embedded in that very staging. While Eastman seeks to portray harmony, there is that inevitable tension you identified arising from what we know to be the fate of America’s Indigenous population. That sense of impending sorrow tinges the bright beauty for me. Curator: Eastman's artistic project raises an interesting historical consideration on artistic production of his time. He, along with many artists like him, shaped not just representations but also, through their renderings, justified expansionist ideas and social dynamics, even without intending such an agenda. His choice of medium here creates an incredible intimacy while rendering a distant time and place. Editor: Right, “The Laughing Waters”… A name promising joy and lightness. But what kind of laughter is it, really? Is it the gleeful gurgle of undisturbed nature or something far more ambivalent – a last chuckle on the edge of transformation? Something to ponder on… Curator: Indeed. An artwork full of depth both intended and captured for the moment.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

This view of Minnehaha Falls illustrated the poem “The Laughing Waters” by Seth Eastman’s second wife, Mary Henderson Eastman. In a picturesque touch, a windblown hunter juts over the water. There was a market for sentimental verse and romantic adventure in the mid-19th century -- think Longfellow’s 1855 tale of star-crossed lovers Hiawatha and Minnehaha by the shores of Gitche Gumee. Mary capitalized on the seeming exoticism of Native life, having collected Dakota stories “during her sojourn in the wilderness,” as one critic put it. This picture was reproduced along with Mary’s writings in an 1852 book called "The Iris: An Illuminated Souvenir."

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.