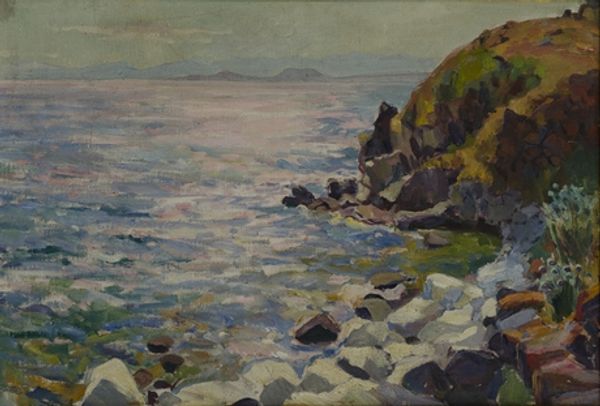

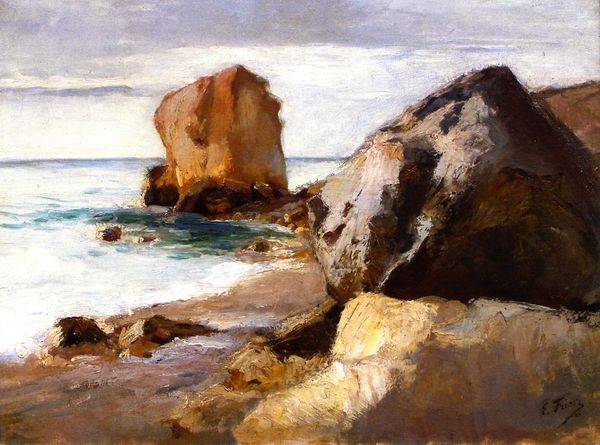

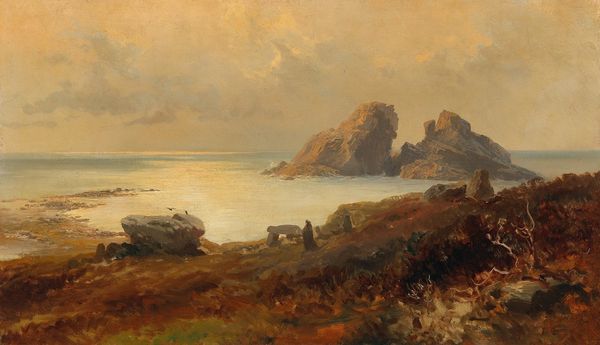

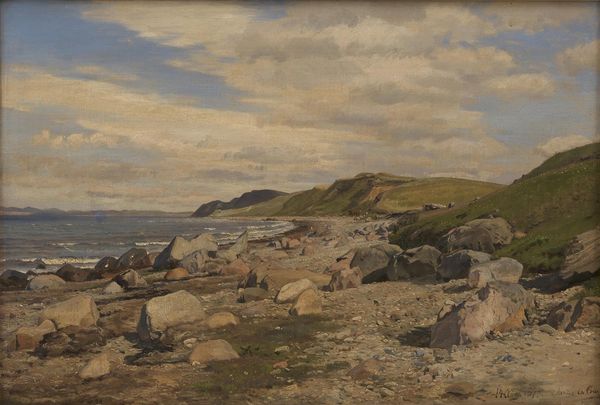

plein-air, oil-paint

#

impressionism

#

plein-air

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

impressionist landscape

#

oil painting

#

seascape

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

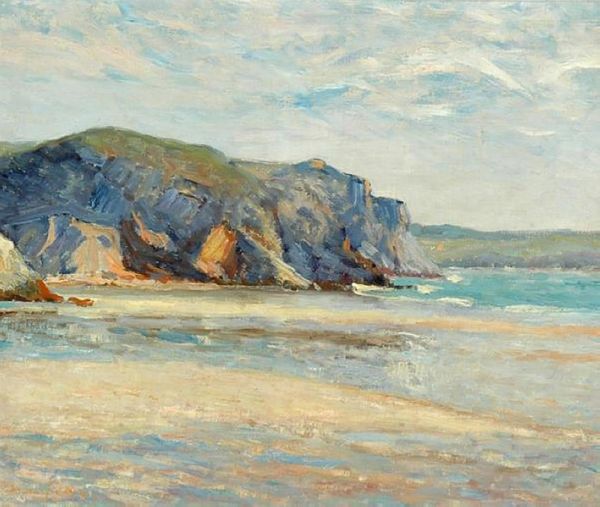

Editor: Here we have Edward Mitchell Bannister’s “Rocks at Newport,” believed to have been painted sometime between 1877 and 1885. It's an oil painting that evokes a really tranquil feeling for me. What strikes me most is how the texture of the rocks in the foreground contrasts with the smoother, almost blurred background. What do you see in this piece? Curator: For me, it is a beautiful encapsulation of labor, materiality, and consumption. Look at how Bannister, working plein-air, grappled with the materiality of oil paint itself to render the scene before him. The visible brushstrokes remind us of the physical act of painting; of Bannister's own labor. He's not just representing nature, but showing us the work *of* representing nature through a specific, valued commodity—oil paint. Editor: That's a really interesting point, looking at it as labor embedded in the materials. I hadn't considered that. So, the paint itself, its texture and application, speaks to the effort involved. But where does "consumption" come in? Curator: Think about the social context: Bannister was an African-American artist in a predominantly white art world. His success allowed him access to materials – those very oils and canvas. Owning and using those materials was, in itself, a form of consumption that pushed against societal barriers that would limit access based on race. Newport, then as now, was associated with wealth and leisure, painting en plein air was linked to that consumer culture. Editor: I see, it connects his access and means of production to his place in society at large. Do you think choosing such a scene--a landscape of Newport--was a deliberate comment on his participation in that world? Curator: Absolutely. The choice of Newport as a subject can be interpreted as Bannister asserting his right to participate in, and represent, a landscape often associated with wealth and privilege. His labor gives us a beautiful object and a challenge to art world conventions. Editor: That definitely changes how I see it. It's not just a landscape, it's a statement of presence and a record of his engagement with both the artistic and social landscape of the time. Thank you! Curator: It shows us that what we call “landscape” itself has never been a neutral thing to depict, because how land is perceived is inevitably linked to how people interact with that place materially, or are kept from it. It’s an honour to think more deeply with you on this, today!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.