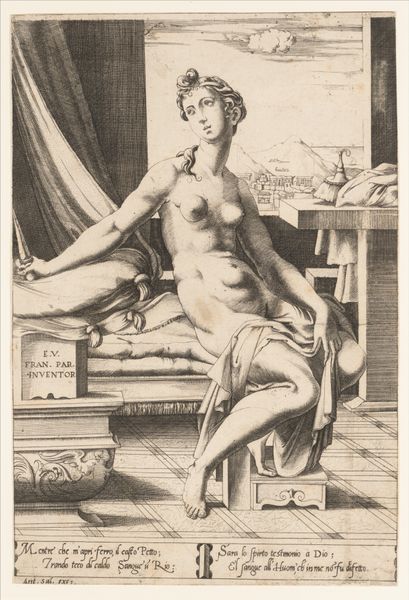

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

men

#

line

#

musical-instrument

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 in. × 6 5/16 in. (22.8 × 16.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have "Euterpe, from 'Twelve Muses and Goddesses'," an engraving by Léon Davent, dating from around 1535 to 1550. I'm struck by the figure's relaxed pose, almost reclining, while holding what looks like a long flute. What do you see in this piece? Curator: What immediately strikes me is how this image encapsulates the Renaissance fascination with classical antiquity, but through a distinct 16th-century lens. Davent appropriates the figure of Euterpe, the muse of music, to legitimize the social function of artistic pursuit. Who has the power to interpret cultural narratives and shape taste in a patriarchal society? What do you make of the subject's passivity versus their active engagement with the instrument? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way, about power structures being embedded here. Her passivity is interesting, almost as if she is waiting to be activated. How does this relate to the visual style? Curator: Notice the stylized lines, the emphasis on the nude form. It idealizes the human body based on classical Greek aesthetics, but also places that body in the service of an allegorical message about art, civilization, and gendered roles. The male gaze, as a sociohistorical construct, shapes our very understanding of beauty, power, and knowledge, particularly during the Renaissance. Where might one find similar allegories to gendered labor in art and culture from that period? Editor: Perhaps in portraits of powerful women of the time. The Renaissance seems ripe for deconstruction! Curator: Exactly. Analyzing the Renaissance through this lens reveals critical discussions on how art reflects, reinforces, or subverts the values of its time. Editor: I now see beyond the surface beauty. This lens provides fresh and much-needed insight into the art's intended meaning and unintended implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.