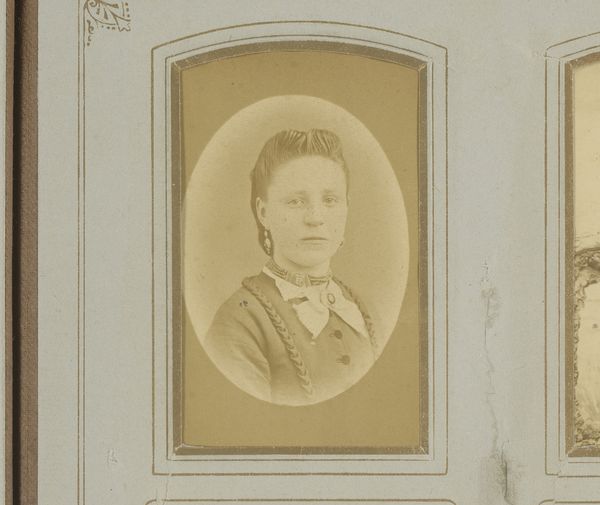

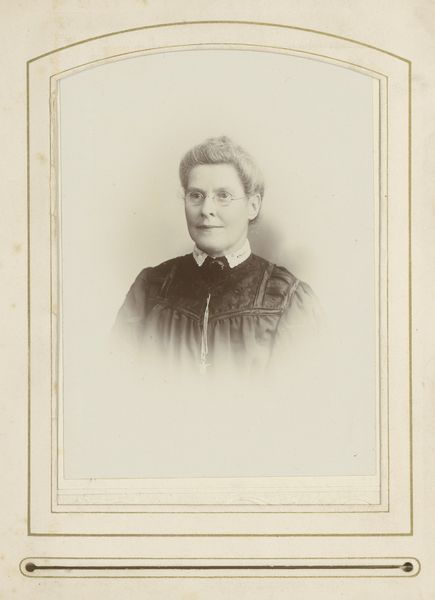

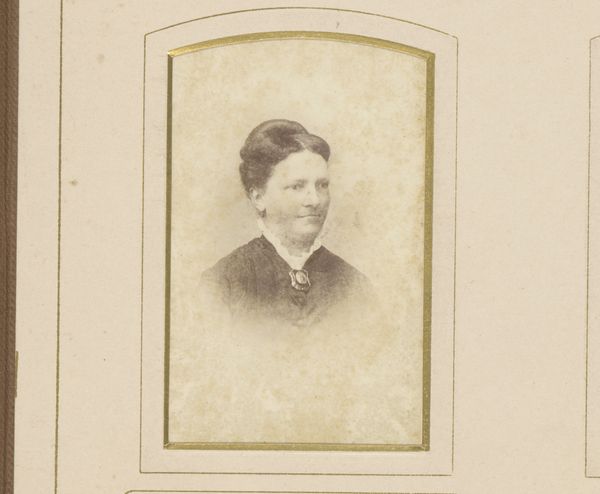

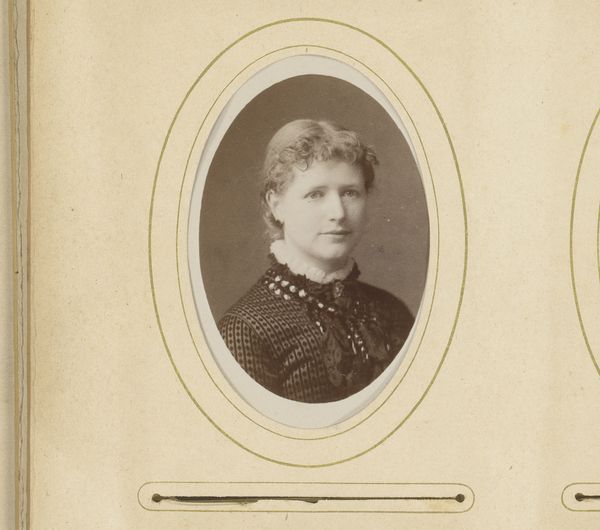

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, we're looking at "Portret van een vrouw," a gelatin-silver print from somewhere between 1860 and 1890, attributed to Ch. Brandebourg fils. It feels very formal, but also strangely intimate. What catches your eye about it? Curator: For me, it’s the photograph’s status as a material object that intrigues. Consider the labor involved. Not just the photographer's, but also the industrial processes necessary to create the gelatin-silver print itself, from mining the silver to manufacturing the photographic paper. Who had access to this new technology and how does that reflect social inequalities of the period? Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't fully considered. Thinking about the process and materials definitely shifts my understanding. But how does that understanding affect our appreciation of the portrait itself? Curator: The subject's clothing provides insight, doesn’t it? The materials, likely machine-made lace and embellished fabrics, point to a level of affluence afforded by the rise of industrial production, affecting fashion and its consumption during this period. Don’t you find it all too neat that her material self speaks volumes about socioeconomic circumstances of women back then? Editor: Definitely! Now I'm looking at this portrait as less about just one woman and more about this specific moment in the industrial revolution and the means that allowed for this portrait to be conceived, produced and even consumed as commodity by her, the subject. It also feels kind of unsettling because this type of photography made painting a thing of the past, like as if the materials consumed traditional practices. Thank you for this. Curator: Exactly, we're seeing a whole shift in art driven by material conditions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.