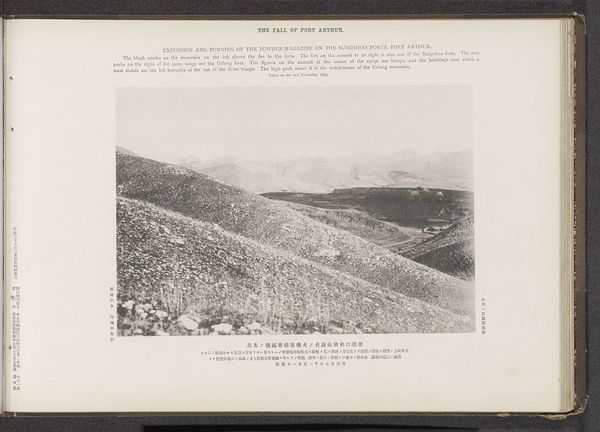

A view of the Chingtow, Mantow, and the Lantse forts and the bodyguards left barracks, Port Arthur Possibly 1894

0:00

0:00

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

homemade paper

#

ink paper printed

#

light coloured

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

paper medium

#

watercolor

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 208 mm, width 277 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

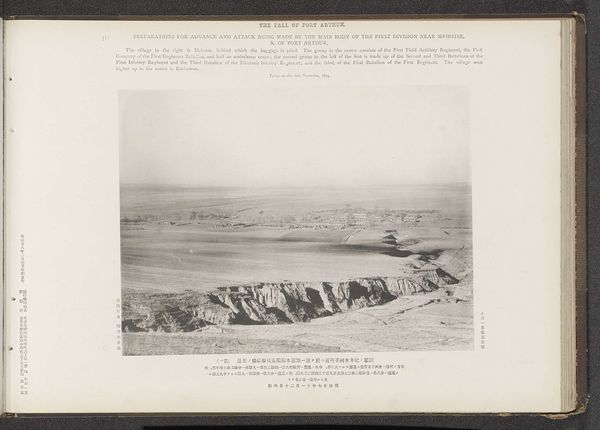

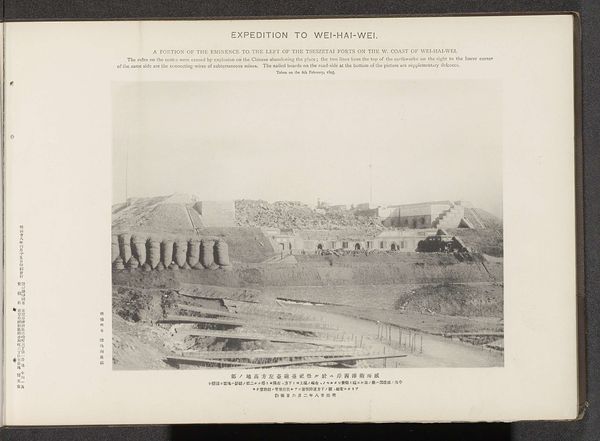

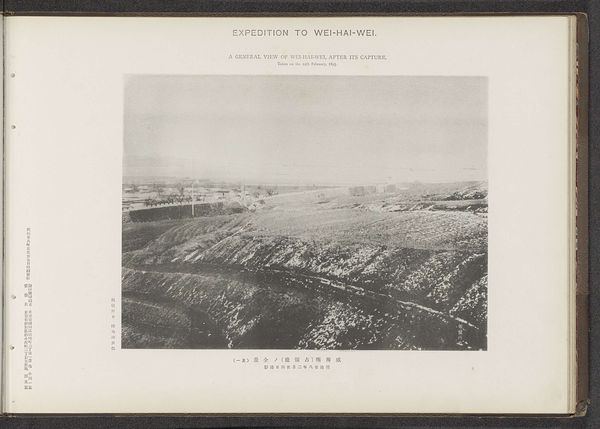

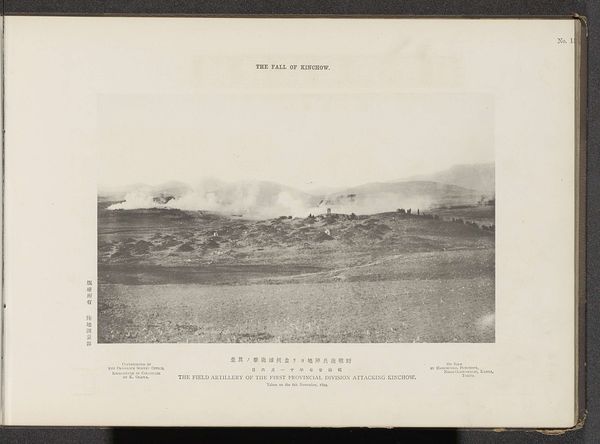

Curator: This work is titled “A view of the Chingtow, Mantow, and the Lantse forts and the bodyguards left barracks, Port Arthur.” It’s possibly dated to 1894 and originates from the Ordnance Survey Office. Looking closely, we see that it's an image presented within a sketchbook—perhaps a personal sketchbook as some tags suggested. Editor: The image is stark. The desaturated palette coupled with that rigid structure evokes such a sense of control and the implied weight of military strategy, wouldn’t you agree? It gives me chills, a cold, detached feeling of observing something powerful and impersonal. Curator: Well, the historical context lends itself to that interpretation. It comes from a time of great geopolitical shifts in that region, with tensions escalating in the lead-up to the First Sino-Japanese War. An image like this wasn’t just a visual record; it was strategic data. Consider how it was employed – by the Ordnance Survey, very possibly intended for use within wider political or military actions. Editor: Absolutely. I can't help but view this image through a critical lens. These meticulous depictions served power. How complicit were the artists in advancing imperial agendas? Also, I'm interested in whose stories are *not* present, whose experiences are rendered invisible within this visual representation. What impact did such representations have on the populations being surveyed, and occupied? Curator: That's crucial. Consider how art schools and surveying offices operated under similar structures of knowledge production, often reinforcing dominant ideologies and class dynamics. Art, even technical drawing, is rarely politically neutral. It’s enmeshed with the structures of power of its day. Editor: Precisely. Thinking about this image alongside more contemporary, indigenous modes of cartography—which often centre communal narratives and place-based knowledge—highlights how maps and similar records can serve as acts of resistance and self-determination. We cannot ignore how these seemingly objective renderings impacted the populations being surveyed, especially indigenous communities dispossessed of their land. Curator: This single image opens up so many layers, doesn't it? It's not just about what's represented, but how and why. It also forces a crucial reflection about our own historical position as we view these older artworks and their complicated past. Editor: Yes. It really urges us to critically engage with these historical records, so as to better interrogate the power dynamics inherent to these sorts of projects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.