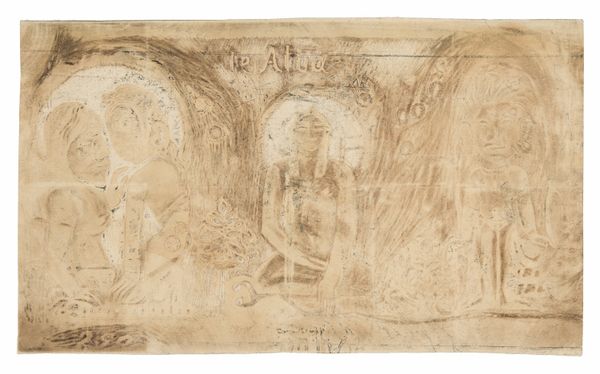

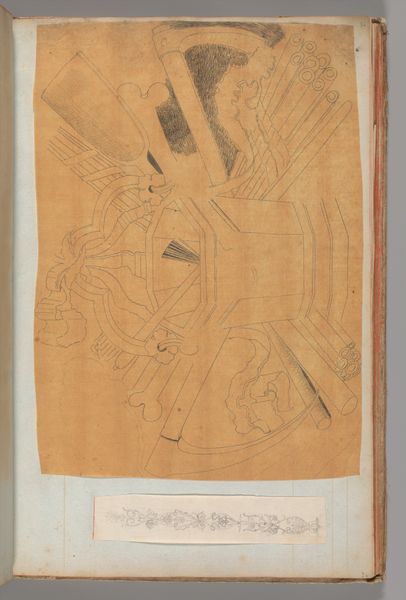

drawing, chalk, architecture

#

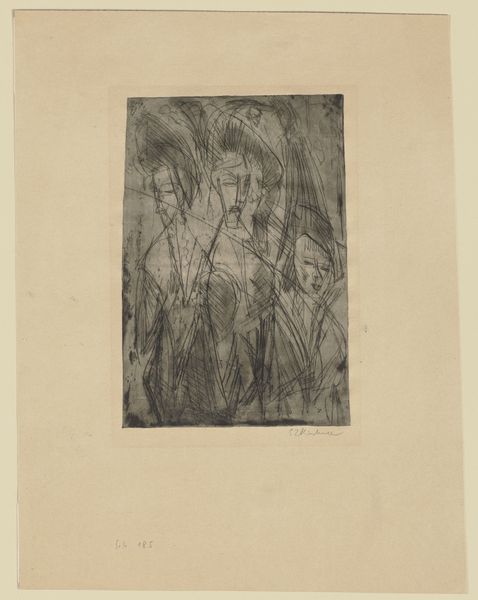

drawing

#

landscape

#

chalk

#

symbolism

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Odilon Redon's "La cloche grave de Sainte-Gudule," a chalk drawing from around 1886-1887. It's quite ghostly. I notice a series of figures, but they almost seem to be fading into the background. What stands out to you in this piece? Curator: I am immediately drawn to the work's linear quality and the restricted palette, qualities that underscore its structure and underlying geometry. Redon here prioritizes line over mass, allowing the eye to perceive the figures through their outlines. Do you observe how the architecture and human subjects seem almost unified by this consistent application of line and tone? Editor: I do. It's as if the people are part of the cathedral itself. But what does that choice signify? Curator: The visual syntax is highly stylized. We might interpret it as a strategy to investigate the essence of form rather than adhering to representational accuracy. Redon is using line and form here as signs, not merely mimetic tools. Semiotically, we can begin to explore the meanings latent in the stark compositions and the relationships between those figures, each of whom represents something from the artist's world. Editor: So, by breaking down these images to almost pure shapes, he is opening it up to more diverse interpretations? Curator: Precisely. In dissolving the figures, Redon makes them—and the architecture of the church itself—more plastic, more available for his exploration of an inner vision. We can look at the work and deconstruct how Redon builds an introspective narrative in shades. The beauty here resides in its intellectual rigor rather than emotional appeal. Editor: I now realize how intentional those stylistic choices were. I initially felt a sense of unease, but that now shifts to awe, witnessing an artistic vision forming right before my eyes. Curator: Indeed. Examining its aesthetic devices lets us look more thoroughly at a landscape of the soul.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.