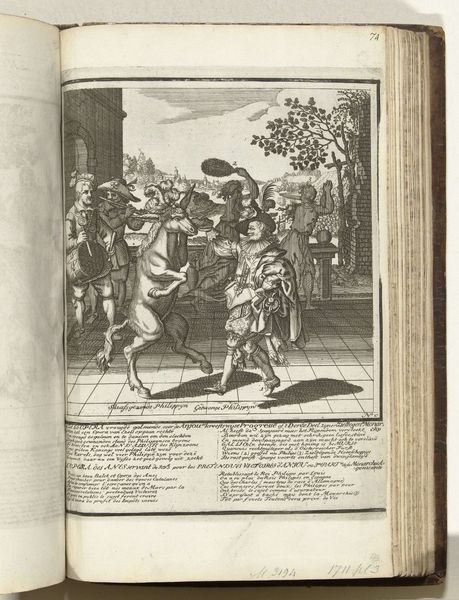

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 180 mm, width 188 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this engraving, "De baljuw probeert de koe van de boer te kopen" by Bartholomeus Willemsz. Dolendo, dating back to 1613. It's currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It’s… well, visually busy. Lots of characters crammed in. The stark contrast and fine lines of the engraving emphasize a kind of raw energy, almost frantic. There’s something unsettling about the scene. Curator: Absolutely. As a print, an engraving, its creation inherently involved a complex network of production. Dolendo, though his name is attached, likely worked within a larger workshop system. This print then circulated, becoming a commodity itself. Think about who had access to these images. What did its widespread availability signify about Dutch society? Editor: So you're placing it within the context of its material conditions. I see it primarily as a stage for a certain drama. Look at the composition. The baljuw, that imposing figure in the feathered hat, occupies the right, with his gesturing hand pulling us in. Then the farmer, on the left, recoils, desperately holding a container over his shoulder. The light focuses sharply on them, staging the moment of confrontation. The cow relegated further back— it is, literally and figuratively, secondary. Curator: Right. And consider how the labor involved in agriculture, in maintaining livestock, gets flattened here. The print highlights the sheriff’s attempt to extract wealth, representing power dynamics and economic realities of the time. Engravings were often moralizing; this speaks to broader discussions of social justice. Editor: I appreciate that contextualization. For me though, it comes down to visual rhetoric. Notice how Dolendo uses cross-hatching to model the figures’ forms. The baljuw and his lackeys contrast sharply against the farmer and his family, in both dress and demeanor. Dolendo employs specific artistic conventions to highlight injustice through form. Curator: It shows how art wasn't this rarefied "creation ex nihilo," but intertwined with craft, social relations, the economics of art. Who produced the paper, the ink? What skills did the engraver need? Editor: Perhaps both. The power lies in the image, its forms capable of sparking debate—visual tools revealing historical dynamics that endure beyond their creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.