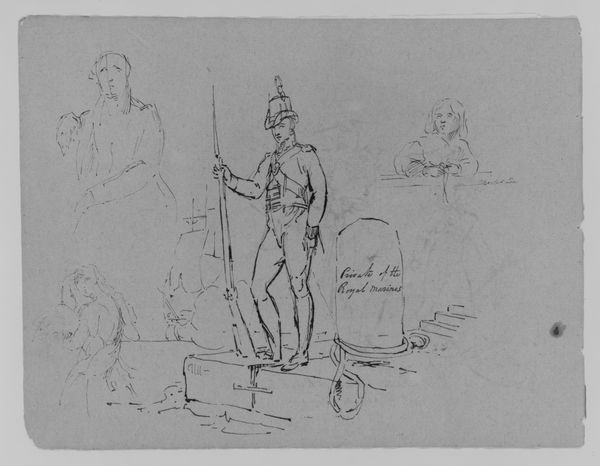

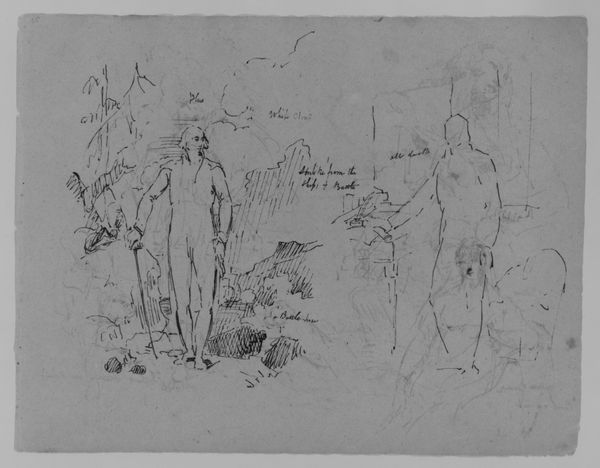

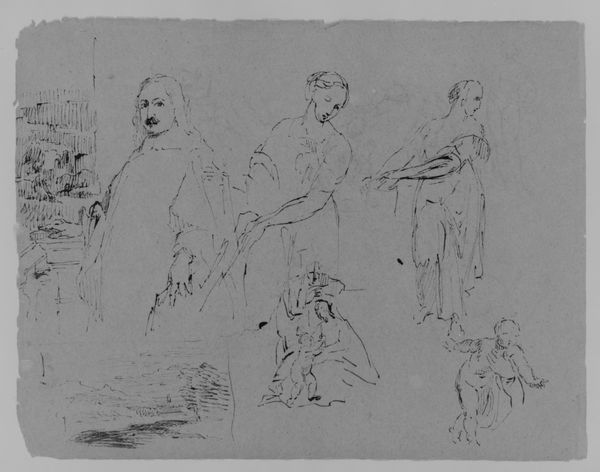

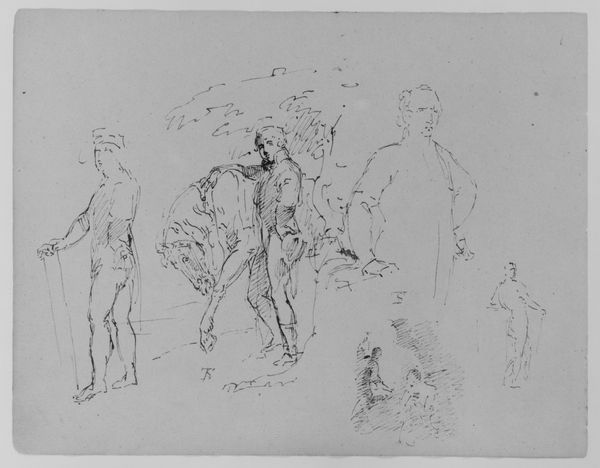

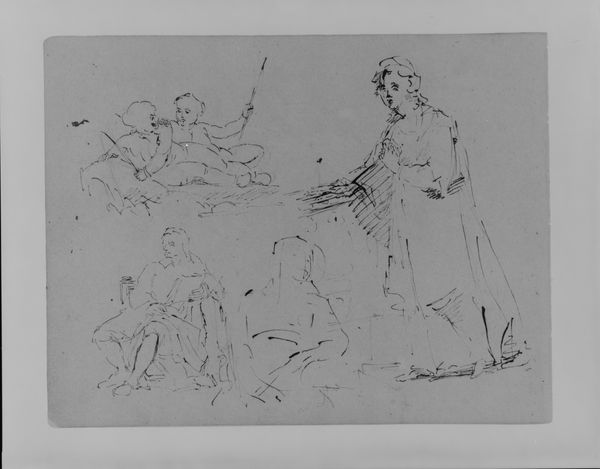

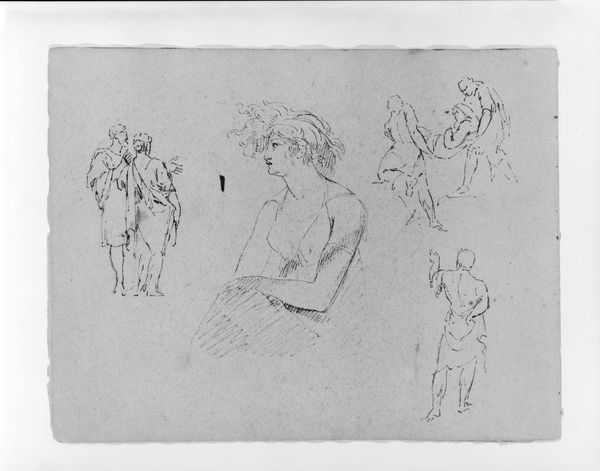

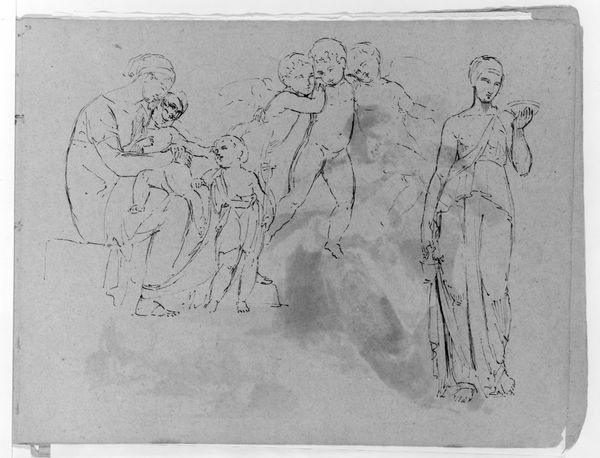

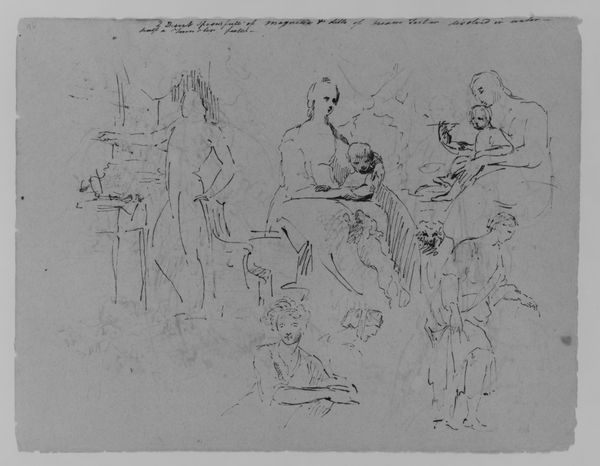

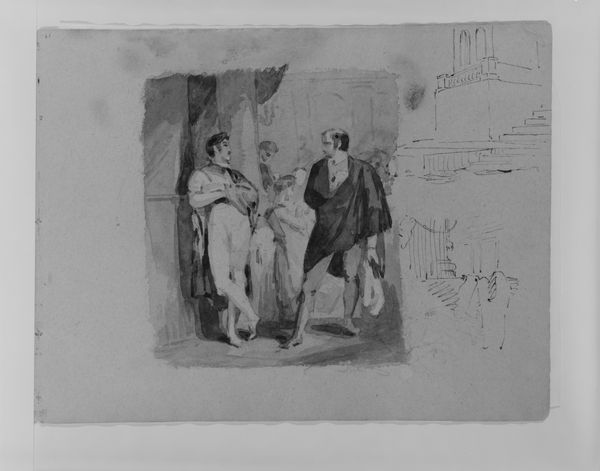

Portrait of a Cleric; Standing Man in Animal Skins; Portrait of a Woman; Man's Head (from Sketchbook) 1810 - 1820

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

#

pencil sketch

#

paper

#

ink

#

child

#

sketch

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

sword

Dimensions: 9 x 11 1/2 in. (22.9 x 29.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a page titled "Portrait of a Cleric; Standing Man in Animal Skins; Portrait of a Woman; Man's Head (from Sketchbook)," created by Thomas Sully sometime between 1810 and 1820. It’s a medley of sketches in ink and pencil on paper. Editor: My first impression is of immediacy—these disparate sketches, sharing space on one page, possess a raw energy, a kind of visual note-taking. I’m particularly struck by the contrast between the carefully rendered figures of what appears to be officers and the softer rendering of the portrait. Curator: Yes, the juxtaposition is key. Let's start with what draws the eye, the detailed study of military figures. Sully was fascinated by military dress and ceremony—an interest stemming from the War of 1812—and you can discern an almost obsessive attention to the textures of their uniforms, the gleaming weaponry... It tells of the socio-political currents swirling around him. Editor: And observe how Sully’s rendering emphasizes their confident posture and gestures. Consider also the opposing sketches and portraits. Note how the composition creates separate visual worlds, almost independent studies brought together solely by the artist's hand. What unites the figures? How is the composition made coherent by medium and line alone? Curator: They were, most likely, preliminary studies for larger, more ambitious projects. We see this compilation was likely for private study. This was typical practice, even within Academic and Romantic artistic circles, but the fact that the study could be considered an artwork points to the changing understanding of art and labor at the time. The means of production were gradually becoming valued. Editor: I see how each separate sketch gains significance, contributing to the whole's semiotic richness. I also find it very Romantic in style and aesthetic—how does it embody that tradition for you? Curator: Very much so. Each sketch becomes more than just a likeness, but a glimpse into an individual. Take, for instance, the standing woman; with that subtle shading, we can easily envision it as a larger canvas, telling a specific, perhaps emotional, narrative. Sully's intention, as was a signature aspect of Romanticism, wasn't merely representation, but expression of deeper truths of the subject, or artist, on paper. Editor: Indeed. What initially seemed like random sketches reveals itself, upon closer inspection, as a dialogue between artist, subject, and history. The composition invites us to piece together stories, to consider the social roles, relationships, and emotions captured on this single sheet. Curator: So, although seemingly disparate, each figure within this collection tells a silent tale, linked not just by their materiality but by the social moment that birthed them. Editor: A single sheet; multiple worlds. What an exquisite reminder of art’s capacity to condense and communicate so much with such deliberate simplicity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.