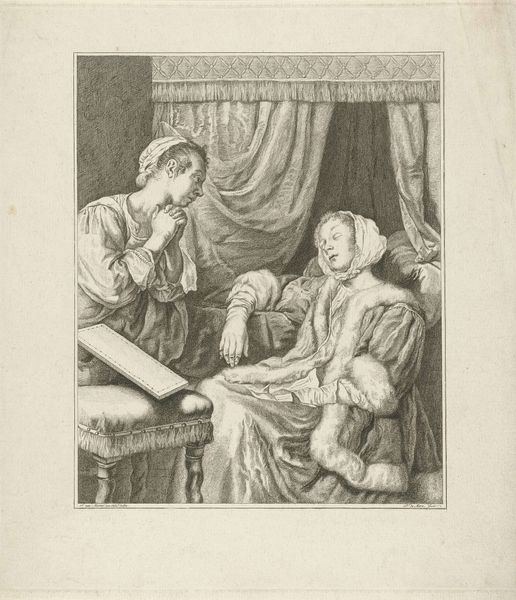

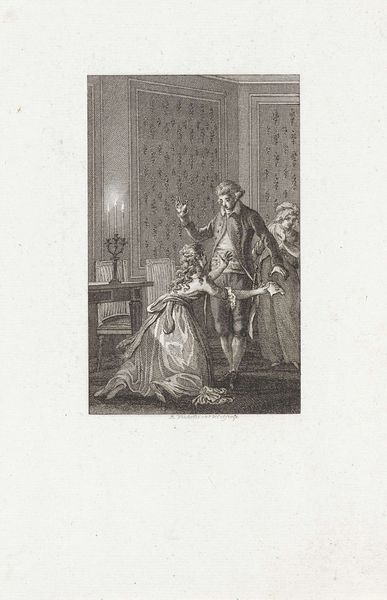

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

figuration

#

19th century

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 95 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: At first glance, the light and shadow at play gives this piece such a sense of interiority and quiet. What’s your take? Editor: It does have that familiar coziness, a certain *intimisme*, wouldn’t you agree? Dirk Jurriaan Sluyter created this engraving, called “Moederzorg”, sometime between 1826 and 1886, currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. What historical narratives does this print evoke for you? Curator: "Moederzorg" translates to "Mother's Care", which is visibly the focal point, literally staged front and center in this domestic scene. The visual echoes resonate with archetypes of motherhood: selfless attention and dedication that transcends specific periods. You almost immediately feel this image holds universal truths. But then there's the context. Editor: Right. You've got a woman meticulously attending to her child's hair, another child mirroring her reflection at a vanity, while a server brings refreshment. The layered social history speaks of affluence and a domestic ideology taking root in the 19th century – separate spheres for men and women, ideas around sentimentality and childhood. Curator: The symbolism! Think of the woman as a guardian. Her meticulous braiding is less about style and more a ceremonial passing down of lineage, protecting through adornment. Even the way the light gently graces her, she's an accessible icon in this intimate chapel of home. Editor: The engraving format is so interesting here as well. Prints made art accessible, disseminating imagery and ideals, reproducing power dynamics and aspirations far beyond the elite. The genre-painting style really underlines that sense of accessible, everyday morality. Curator: Exactly. And the strategic staging only highlights the cultural construction. Each object tells us about this cultural obsession to illustrate family cohesion as some sacred experience. But even in rendering the "sacred", the ordinariness can't be dismissed as merely sweet. Editor: Precisely, which circles us back to considering reception then: who bought it, displayed it, interpreted this representation? Did the rising middle-class internalize the role presented? Curator: Perhaps by displaying "Moederzorg" then, they showcased not merely ownership but investment in constructing self-image that aligned with larger value narratives. A constructed personal brand. Editor: An exercise in what Pierre Bourdieu might describe as "cultural capital", visibly reinforcing social standing and aspirations. In its gentle detail, "Moederzorg" hides a potent declaration of belonging. Thanks for illuminating that point, your perspective really does change how the work speaks today. Curator: The same can be said of your analysis. By layering this piece, "Moederzorg" almost feels less like a picture and more like a historical portal for our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.