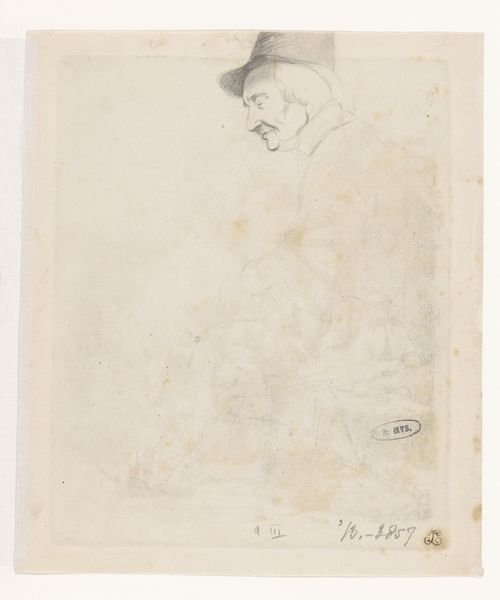

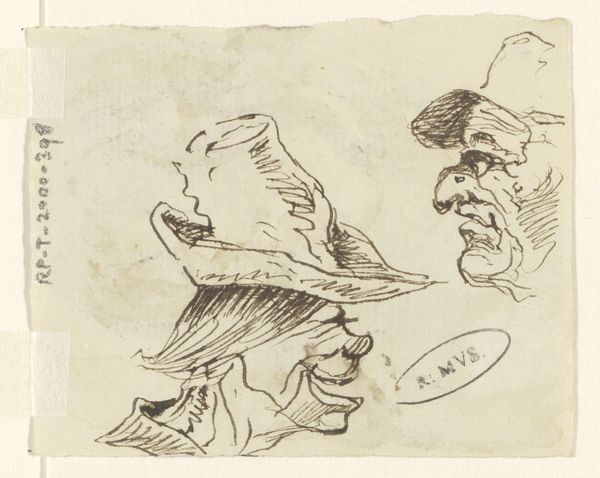

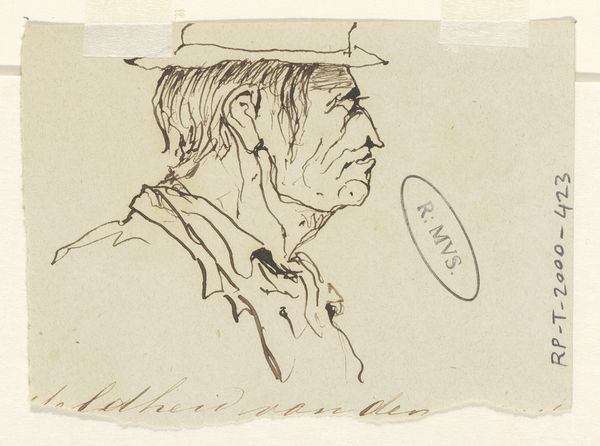

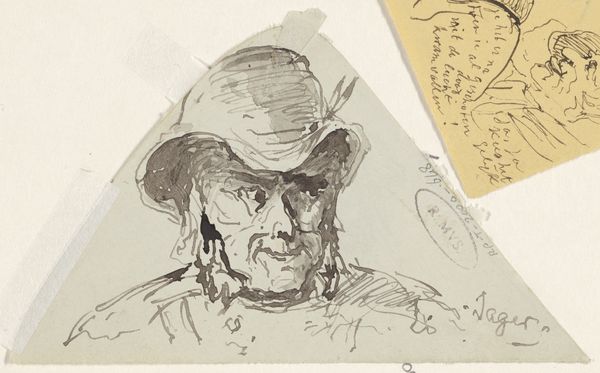

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 98 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

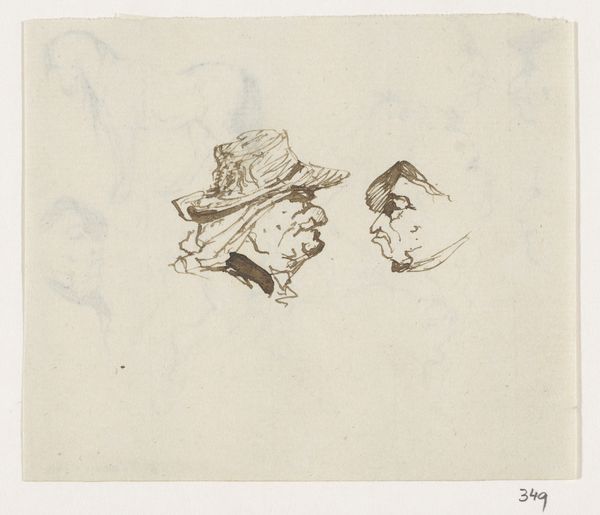

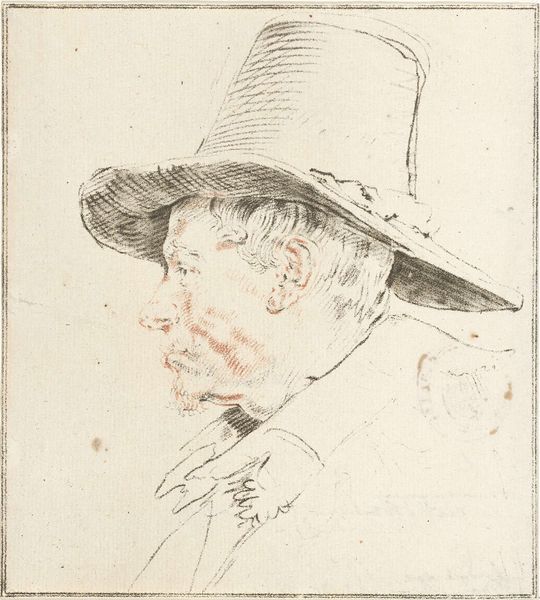

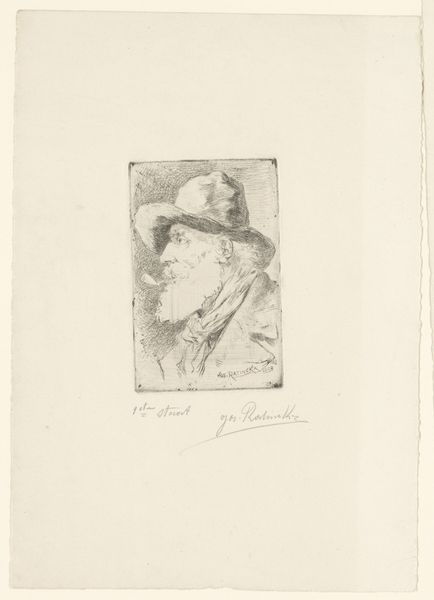

Editor: Here we have Johannes Tavenraat’s “Kop,” a graphite drawing from sometime between 1840 and 1880. There’s a certain vulnerability to this sketchy profile, almost as if we’re catching a glimpse of someone unaware. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a portrait, yes, but also an exercise in power dynamics typical of 19th-century academic art. Consider who was being portrayed and who was doing the portraying. This "Kop," or head study, wasn’t just about capturing a likeness, but about codifying social hierarchies. What might the class and racial identities of both the artist and sitter reveal about this dynamic? Editor: That's a good point! It really places the work within a broader historical context, beyond just aesthetics. Is there something about the style too? I see it's labeled as Romanticism, and I thought the "Romantic" part was only about showing pretty things! Curator: Romanticism wasn't simply about beauty; it also delved into power structures, the exoticized ‘other,’ and the subjugation of marginalized people through aesthetic representation. Tavenraat’s use of line and shadow, while seemingly innocent, contributes to a visual language that either reinforces or challenges existing social narratives. It’s our job to figure out which. Do you think it elevates the person he drew or judges them? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way before, but now I see how much more there is to unpack. It really goes beyond just the surface. Thank you! Curator: My pleasure! Examining art through lenses of power and identity helps us engage critically with the past and understand its continued relevance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.