painting, watercolor

#

painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 47.5 cm (height) x 63 cm (width) (Netto), 62 cm (height) x 78.2 cm (width) x 9.2 cm (depth) (Brutto)

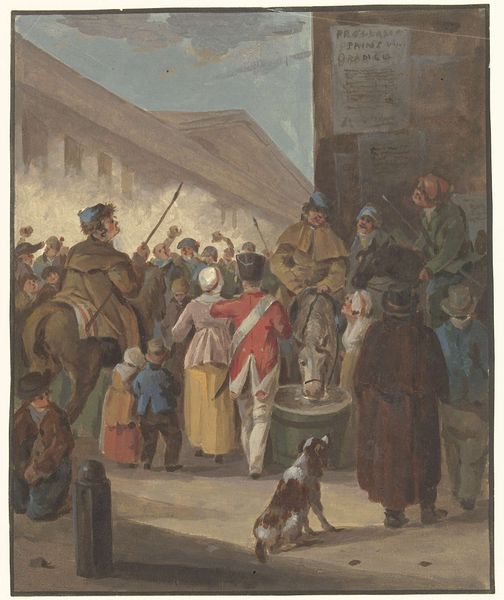

Martinus Rørbye's depiction of The Prison of Copenhagen presents us with a stark archway, a symbol steeped in historical and cultural significance. The arch, a recurrent motif throughout art history, traditionally signifies both passage and confinement. Consider the Roman triumphal arches, gateways to imperial power, or even the arches of religious architecture, promising spiritual passage. Yet, here, in Rørbye's painting, the arch looms over a prison, suggesting not freedom but restriction. This visual paradox carries echoes of Piranesi's architectural fantasies, where vast, oppressive structures evoke a sense of psychological entrapment. The arch becomes a symbol of the complex interplay between exterior realities and interior states, where the promise of passage is subverted by the reality of confinement. The stark contrast between the vibrant street life outside and the somber prison walls generates an emotional tension, engaging the viewer in a subconscious exploration of freedom and constraint. Like a recurring dream, this symbol resurfaces throughout history, evolving, yet always retaining its inherent duality.

Comments

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

During the years where Rørbye concluded his time at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, he did large numbers of drawn landscapes and views of Copenhagen and its environs, as well as paintings showing scenes of street life in the Danish capital.Familiar types from everyday lifeThe works, which proved very popular with buyers, were characterised by their panoply of familiar types drawn from everyday life and by their moralising allusions, making them something other than simple snapshots of life.The architectural surroundingsThe street scene from the Nytorv in Copenhagen strikes an edifying note even with its architectural surroundings. C.F. Hansen’s prison is a principal piece of Golden Age architecture. It is “eloquent” architecture with a stern look intended to instil fear of the consequences of any crime.The painting's figuresIn the background a young man is asking an older moneylender for a loan, while another young man points an admonitory finger to the debtor’s prison behind him. To the left of the arched doorway the transaction between the old and young women refers to the scales of Justice; the young dandy in the middle of the picture, his hand in his bulging pocket, sends lusty glances at the young mother to the right.The small signs of the characters’ less than appealing traits are commented on by the old man in the foreground - a misanthrope who does not even put out his light in broad daylight.?

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

statensmuseumforkunst about 2 years ago

⋮

Rørbye’s moralising depiction of street life in Copenhagen strikes an improving note with its architectural frame alone. With its forbidding aspect, C.F. Hansen’s prison struck fear of the cost of any crime into citizens. In the background a young man is asking an older moneylender for a loan, while another points tellingly to the debtor’s prison behind him. The young dandy in the middle gazes lustily at the young mother to the right. Depictions of life within the town walls were popular at the time. Typical characteristics of the genre included a plethora of types familiar from everyday life and moralising narratives rather than documentary accounts. Such art allowed the affluent to confirm their own moral superiority in images ensconced between family portraits, safely secluded from actual events.