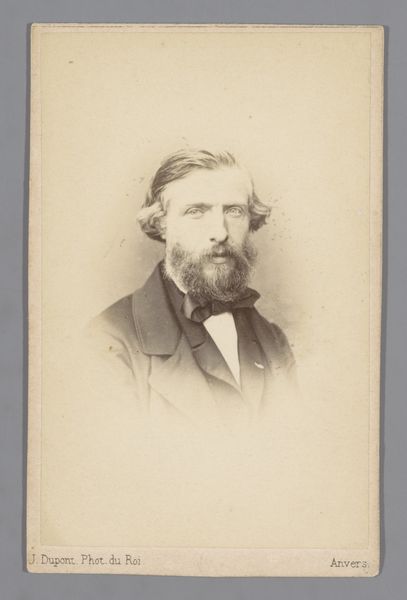

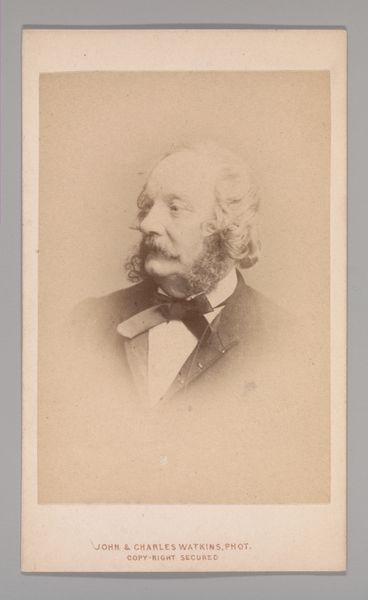

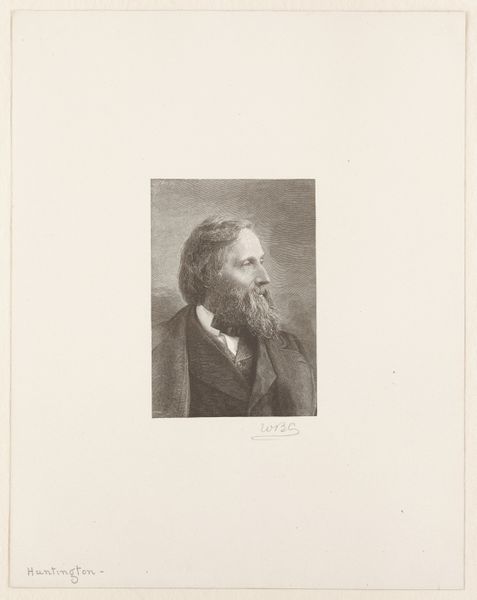

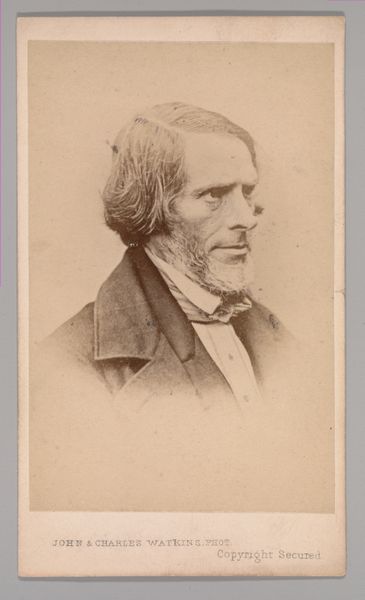

Dimensions: 6.7 × 4.2 cm (image); 9.1 × 5.8 cm (paper); 10.3 × 6.3 cm (mount); 11.4 × 7.6 cm (hanged paper)

Copyright: Public Domain

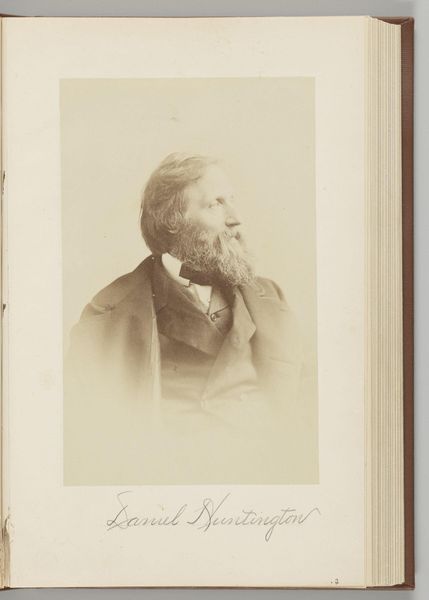

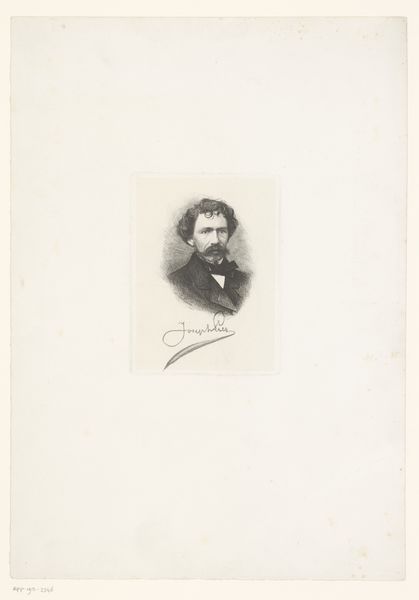

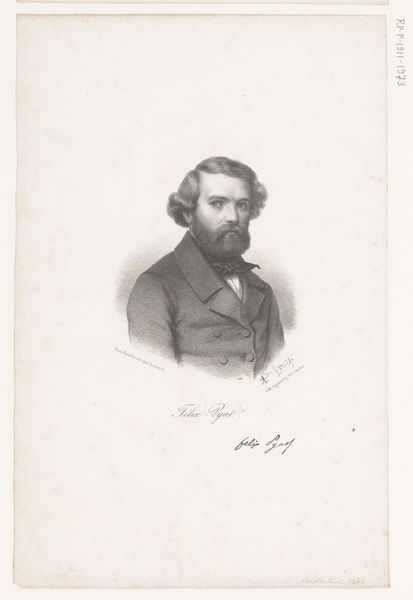

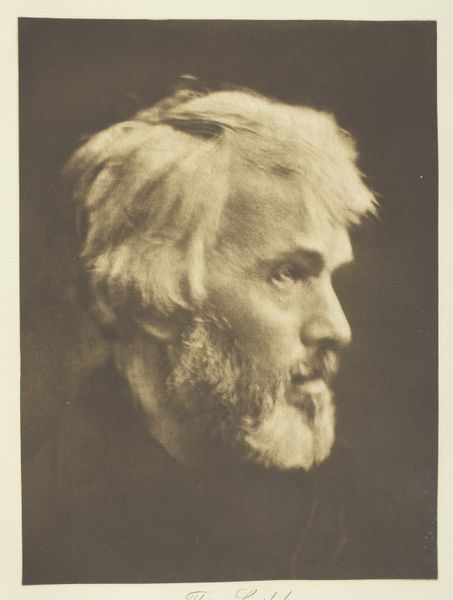

Curator: What a fascinating piece! This is an albumen print portrait of Thomas Carlyle by Elliott & Fry, dating from 1863 to 1869. It now resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s a bit dreamy, isn’t it? All soft edges and muted tones. Makes you feel like you’re peering into the past. A man captured but just barely. The photographic process softens his features. What an intriguing tension, like a memory trying to be grabbed out of thin air. Curator: Yes, the soft focus and delicate tonal range are quite characteristic of pictorialism, even at this relatively early stage in its development. This was very deliberate—a way to elevate photography to the level of art. Think about the labor involved. Preparing the glass plates with the albumen, exposing the image, the darkroom work... Editor: That albumen gives it this incredibly subtle glow. I find myself pondering what it must have been like, being photographed in that era. Not a quick snap, but a dedicated undertaking—like the gentleman certainly presented himself well enough. What would that do to a person's sense of self? What a formal procedure with its class-infused decorum. Curator: I think you've hit on something. Carlyle was a renowned essayist, historian, and philosopher—very much a public figure crafting a persona. He was known for his strong opinions and often critical social commentary. The choice of Elliott & Fry, a very well-known and successful photographic studio specializing in portraits of prominent figures, seems intentional. He understands photography's power to shape and disseminate an image of himself, for public consumption. Editor: Absolutely. Photography isn't just a mirror reflecting reality, is it? There is artifice in everything we see! Each photograph, especially portraiture, must present both sitter and photographer each grappling in different power dynamics. Curator: In closing, considering how photographs and images are consumed so rampantly these days. Seeing images with tactility and that sense of careful consideration—offers an invitation to approach image-making differently, and also more compassionately. Editor: Exactly. What are images beyond surfaces if we fail to unpack its making, production, and dissemination? We’ll never know for sure how much of that is in his choice. What is preserved of history here through medium and its production? Intriguing isn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.