Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

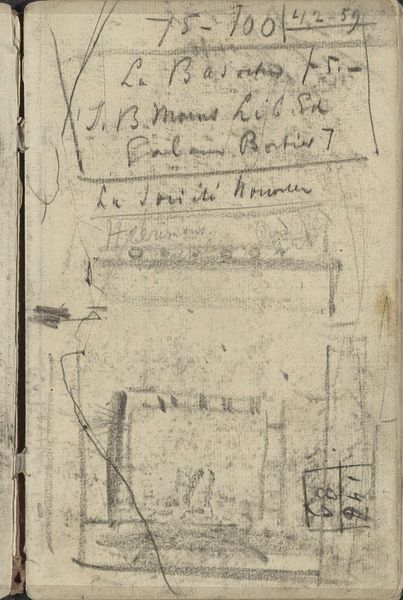

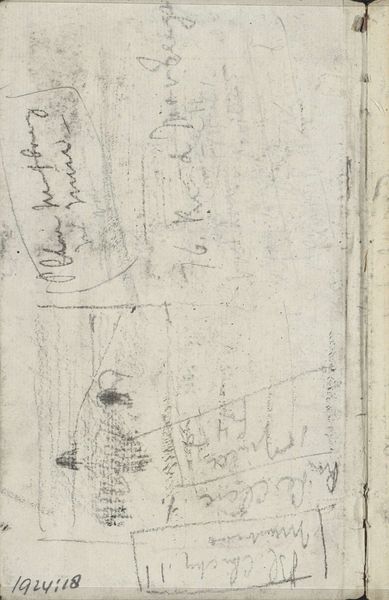

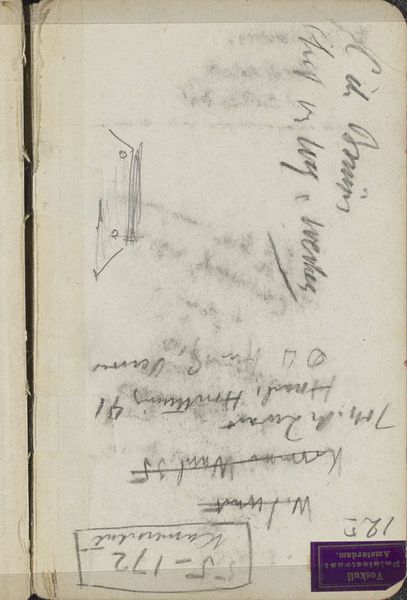

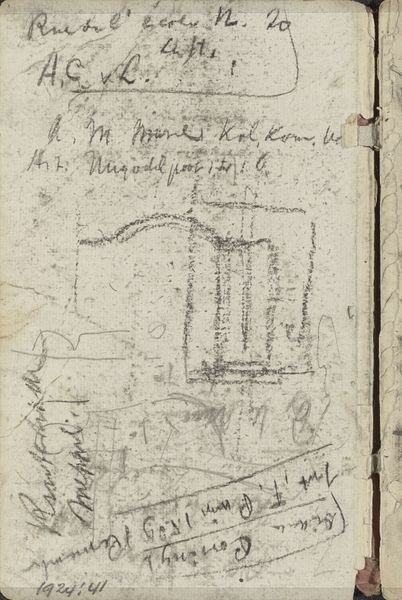

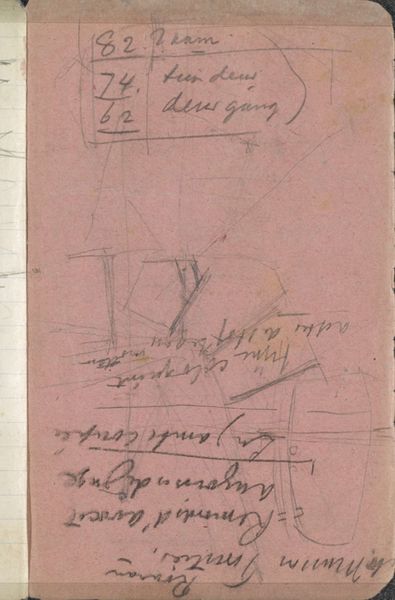

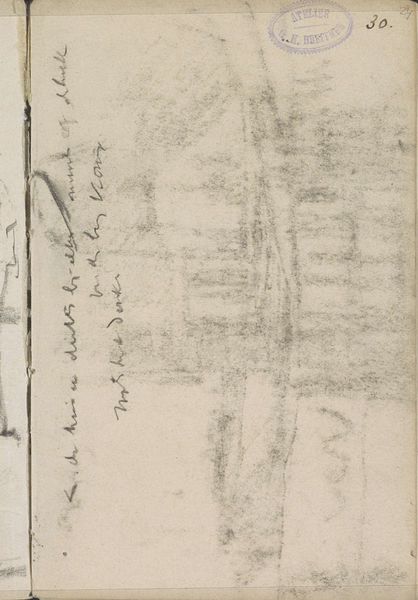

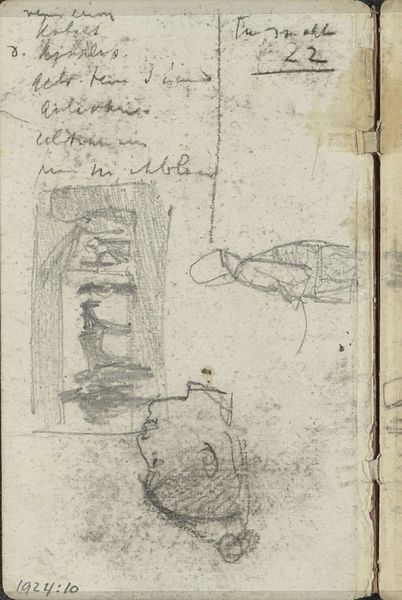

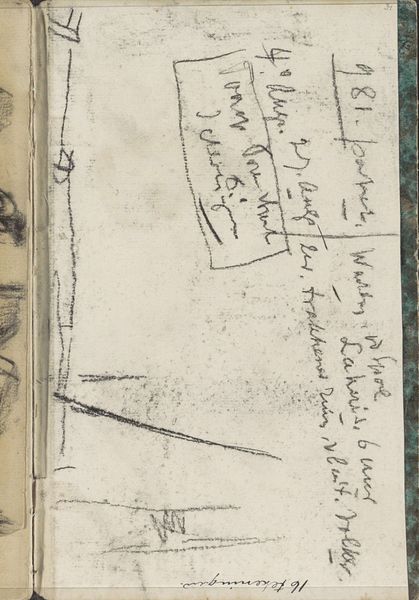

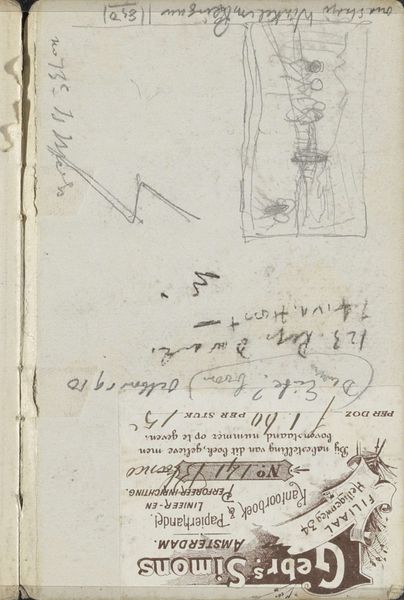

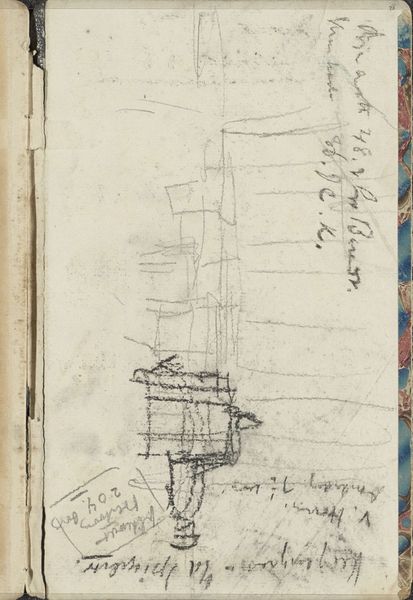

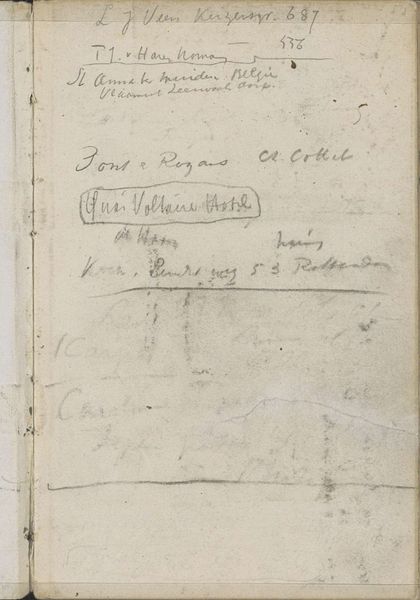

Editor: Here we have a sketchbook page by George Hendrik Breitner, titled "Studie," from around 1886 to 1903. It's rendered in pencil and pen on paper. It feels intimate, like a private glimpse into the artist’s thoughts. What jumps out at you when you look at this piece? Curator: I'm drawn to the juxtaposition of the textual and visual elements. Consider the time it was created: Breitner, working in this Impressionist era, engaged with rapid urbanization and societal shifts. Sketchbooks became sites for capturing fleeting moments but also for recording reflections on those changes. Does the handwriting above suggest a potential narrative he intended to accompany these sketches? And how might these architectural forms reflect the reconstruction of Amsterdam’s urban landscape at the time? Editor: That's interesting – I hadn’t thought about the text as an intentional part of the composition. So, you're suggesting it’s not just preliminary note-taking, but an integral layer? Curator: Precisely. It invites us to consider the act of witnessing itself. Whose stories were being told—or erased—during this rapid reshaping of Amsterdam? Breitner often focused on working-class life. Might these sketches represent sites relevant to those narratives? How might their voices, perspectives, be inscribed – or perhaps inscribed—within the city itself? Think of it as Breitner recording how urban policies influenced individual experiences in an era that struggled with social inequalities. Editor: I see it now. It makes me think about how public spaces are contested, even in sketches like these. It makes me see a kind of statement. Thank you. Curator: And thank you; reflecting on art through such dialogues keeps historical analysis alive. It’s essential to view art as a historical document shaped by social power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.