tempera, painting

#

medieval

#

tempera

#

painting

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

early-renaissance

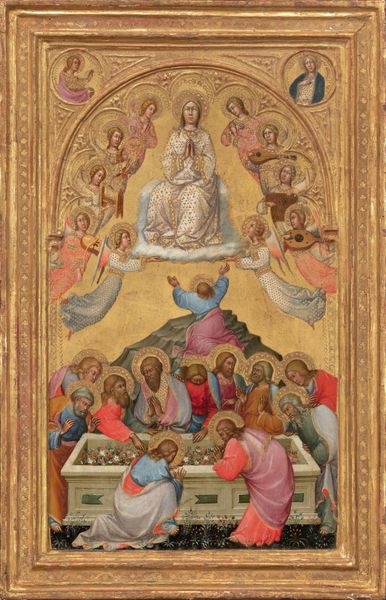

Dimensions: 43.5 x 32.4 x 0.4 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is "Pentecost," a tempera painting from around 1420-1430 by an anonymous artist, currently held at the Städel Museum. It’s striking how everyone's gaze is directed upward, and there’s this somber mood despite the supposed miracle. What do you see in this piece, beyond the obvious biblical scene? Curator: Beyond the surface, I see a deeply coded representation of power dynamics. The gathering of apostles around the Virgin Mary isn't simply a depiction of religious communion, but an assertion of patriarchal authority legitimized through divine mandate. Note how the figures around her almost act like framing devices, which creates a fascinating gendered composition. Editor: Framing devices? That's interesting. Are you suggesting the composition reinforces existing societal structures? Curator: Precisely. This isn’t merely about portraying a historical event; it’s about encoding a message that reinforces social hierarchies. Consider also that Mary occupies the very centre and bottom-centre positions, a potent, complicated intersection of power and subjection within the composition itself. How might we read that? Editor: So, you're viewing the positioning as both a focal point, but also indicative of her prescribed role? Curator: Absolutely. Early Renaissance art, particularly religious works, was a powerful tool for social engineering, subtly dictating gender roles and solidifying the church’s authority. It's about deciphering those visual cues to understand the painting’s intended influence. Editor: It makes me think about who the intended audience of that would be, and whose power structures this is reflecting. Curator: Indeed. It’s essential to consider who this artwork served and whose narratives it prioritized and, inevitably, whose narratives it erased. Editor: Wow, I hadn't thought about it that deeply before. Thank you. Curator: Of course. And isn't that the most exciting part of art history, continuously questioning what we thought we already knew?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.