Dimensions: height 33.1 cm, width 41.5 cm, depth 3.3 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

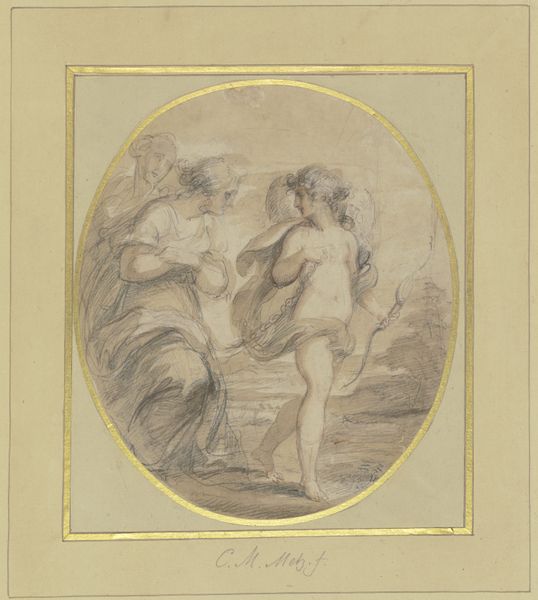

Editor: Here we have "Two Fête Galante Scenes," a painting from around 1795 by an anonymous artist. It has such a dreamlike, romantic quality. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: Immediately, I'm drawn to the materiality of it all. These "fête galante" scenes, popular in the Rococo period, often depict idealized aristocratic leisure. But consider the context of 1795 – the French Revolution was in full swing. Look at the production: Who made the paint? How was the canvas prepared? Was this an aristocrat commissioning escapism, or someone else entirely imagining their life? Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn’t considered the revolution’s impact. I guess I saw it more at face value as a representation of idealized pastoral life. Curator: And it is, superficially. But even in its beauty, it’s speaking to material conditions. The fine details are crafted from labor and materials – who is it ultimately *for*, and who benefits from its consumption? Is it a nostalgic look backwards or a speculative reach forwards, made by the invisible hands who served such scenes? How might we interpret that in terms of social stratification and class dynamics? Editor: That gives the piece a whole new layer of complexity. The leisure depicted isn’t just pleasant; it's produced. Curator: Precisely! Consider also the frames. This decorative flourish consumes more material – gilding, wood – demonstrating access and disposable income of a certain class and how art plays into material expression of that economic position. Editor: So, by analyzing the materials and means of production, we can unpack the social and economic realities of the time. That really changes my perception. Curator: Exactly. Thinking about art this way encourages a critical understanding of the society that birthed it. It moves us away from purely aesthetic appreciation towards something much more historically grounded. Editor: I’ll never look at a "fête galante" scene the same way again! I appreciate the labor, materiality, and consumption associated with creating such works. Thanks for shedding new light!

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In reverse painting on glass, the image is painted on the back –foreground details first (in reverse to normal practice). In the 18th century, Chinese painters, particularly in Canton, specialized in this technique. One such artist copied these two scenes for Van Braam Houckgeest after the work of the renowned French painter François Boucher. They are still in their original 18th-century frames.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.