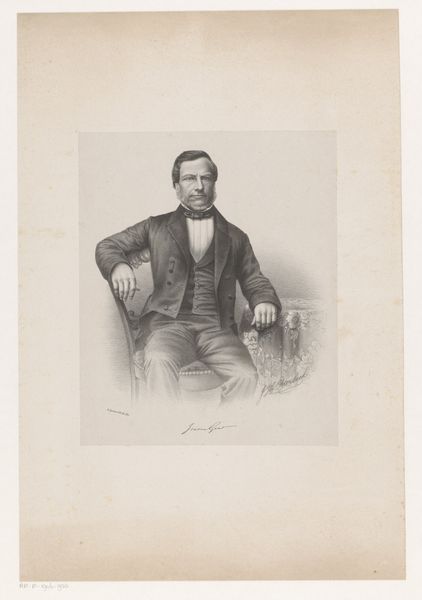

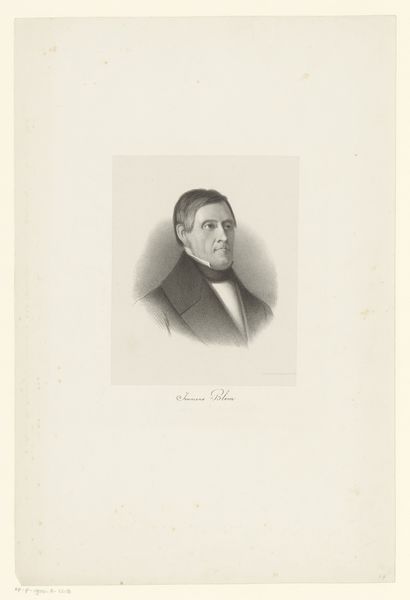

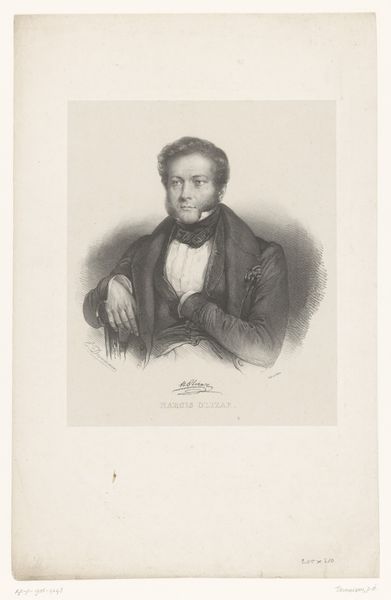

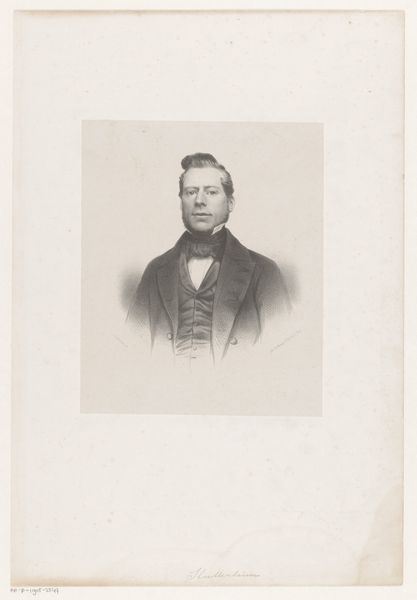

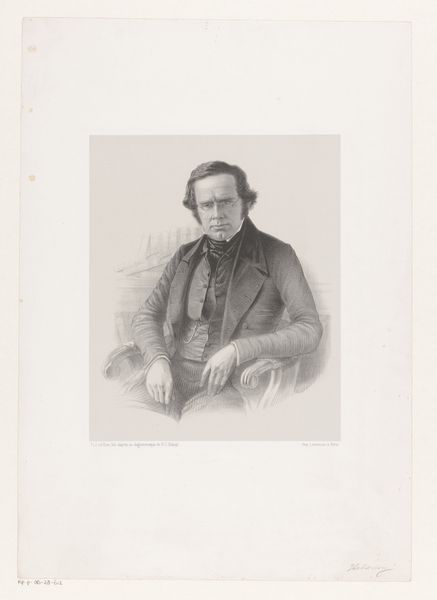

print, paper, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

paper

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 377 mm, width 281 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Isaac Wilhelm Tegner's "Portret van Ludvig Ahlberg," created between 1850 and 1893. It’s an engraving on paper. It's fascinating to consider the time and labor invested in each line. What story does this printmaking process tell us? Curator: A great starting point. The choice of engraving, particularly during this period, signifies a shift in the mass production and distribution of images. Forget the unique artistic "aura"; think instead about accessibility. What class of people had access to these portraits? Were these for general audiences, or a select group? Editor: Given his medals, I would guess that he was of some standing, which suggests that maybe these portraits had some intention of creating reputation and celebrity of him, perhaps circulating it in specific professional and upper class social circles. But isn’t engraving laborious, requiring highly skilled artisans? Curator: Exactly. Think of the socio-economic dynamics at play. An artist like Tegner relies on skilled labor for reproduction, creating a demand within a specific artisanal market. Each print becomes a testament to skilled labor, a material document of a very specific system of production, in some ways akin to the factories emerging in Europe at the time. Editor: So, rather than a focus on aesthetic value, we look at its material production and social function? Was the paper itself a valuable commodity, or perhaps an easily available mass product, that was chosen in function to who it would circulate to? Curator: Precisely! The material, the process, the implied audience – they all become part of the artwork's meaning. Think of the cost of paper, the time spent engraving versus other quicker reproduction methods available at the time. All of those contribute to the artwork's social positioning. It's a powerful way to read beyond the surface. Editor: I never considered portraiture from that angle before. Now, I see a web of connections involving class, labor, and the economics of image production! Thank you. Curator: A materialist lens changes how we value artistic work. It grounds art in reality and brings a lot of these dynamics to light.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.