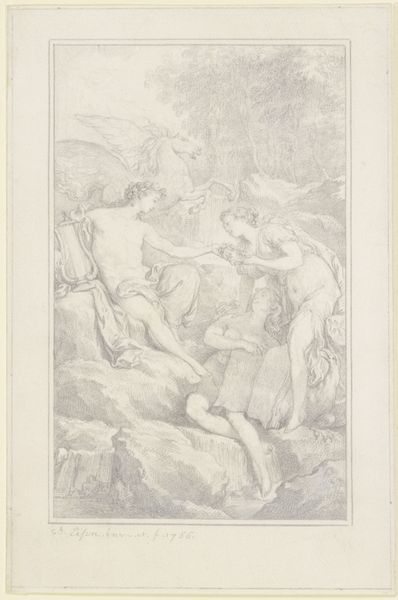

Heavenly Ganymede, plate XV from the second issue of Specimens of Polyautography Possibly 1804 - 1807

0:00

0:00

drawing, lithograph, print, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

allegory

#

lithograph

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

nude

Dimensions: 312 × 243 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is Henry Fuseli's lithograph, "Heavenly Ganymede," created sometime between 1804 and 1807. Part of a series titled "Specimens of Polyautography", it captures a moment of divine intervention. Editor: The scene is striking, almost violently dramatic. The stark contrasts immediately draw the eye. The looming figure seems less like a gentle abduction and more like a forceful overtaking. Curator: Fuseli was known for his engagement with the sublime and the emotional intensity of Romanticism. This work would have been quite radical considering the era and its obsession with idealized beauty. Consider how his choice of lithography, relatively new at the time, democratized printmaking and made such arresting images more widely accessible. Editor: Right. Ganymede has been interpreted so many ways through history—as embodying youthful beauty, male love, divine favor. The upraised arm, the angle of the head, the youth with the jar—these resonate deeply with cultural memory and established notions surrounding this scene. Curator: Yes, and I wonder if Fuseli was consciously playing with those layered meanings. The image was circulated, distributed and, above all, consumed in specific socio-political contexts. The nude male body carried implications within the artistic establishment and among its viewers. What visual narratives did his contemporary audiences construct around this Ganymede? Editor: Precisely. There's such rawness conveyed through Fuseli's lines and form, which gives it lasting emotional weight. Curator: By choosing lithography, Fuseli circumvented the Royal Academy’s gatekeeping apparatus, which promoted some narratives, approaches, and voices at the expense of others. So much of art history hinges on those questions of access. Editor: Well, seeing this work certainly provides some fuel for thinking. It goes beyond simply illustrating myth, and makes one confront something about our own history with iconography. Curator: It’s a provocative and powerful image that speaks volumes about both artistic intention and the context in which it was produced and distributed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.