drawing, wood

#

drawing

#

furniture

#

wood

#

watercolour illustration

#

academic-art

#

watercolor

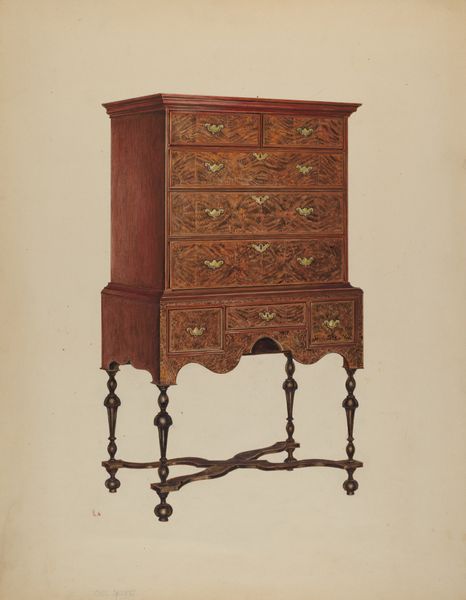

Dimensions: overall: 55.1 x 62.9 cm (21 11/16 x 24 3/4 in.) Original IAD Object: 49" high; 44 1/2" wide

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Let’s discuss Ferdinand Cartier’s rendering of a desk, dating circa 1941, crafted in watercolor and drawing, which emphasizes the material itself as its subject. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It feels very...grounded. Solid. Maybe even a little authoritarian? All that deep wood grain and formal symmetry speaks of a specific power structure, or perhaps aspiration. Curator: Note the draughtsmanship here. The meticulously rendered texture of the wood. The way the light catches the edges of the drawers. Observe also the structural components and how they interact with one another; the subtle shadowing, delineating shape and suggesting three-dimensionality. The artist has skillfully applied academic principles to capture this form. Editor: Yes, but think about who would own a desk like this. In the 1940s, furniture like this, suggests privilege. The design itself—ornate, imposing—reflects ideas about wealth and status, especially when so many didn't have stable housing during or after the war. Also, it evokes a colonial aesthetic that perpetuates historical exploitation and reinforces systems of inequality, no? Curator: You raise important points about potential social implications, however I would like to respond with an observation of Cartier’s deliberate placement of the drawers. The rhythm of the arrangement, repeated in a series across the horizontal plane. What does this geometric sequence represent beyond mere functionality? Could it also convey something fundamental about order, and reason? Editor: Perhaps, but even the idea of "order" itself needs scrutiny! In what ways does such imposed organization reinforce social hierarchies? Those drawers could signify a carefully compartmentalized life that normalizes systems of oppression, for those not allowed to organize themselves similarly. Curator: We might consider, then, the broader concept of display – in which form is presented for consumption, both literal (to organize) and interpretive (for the observer), it provides both a visual and functional component to examine how the maker uses his form and intention. Editor: It encourages me to reconsider whose voices and stories aren’t reflected in such objects or within our dominant interpretations of “art.” This is very much what makes the social and political understanding of such design valuable, because it promotes conversation between art history and contemporary concerns.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.