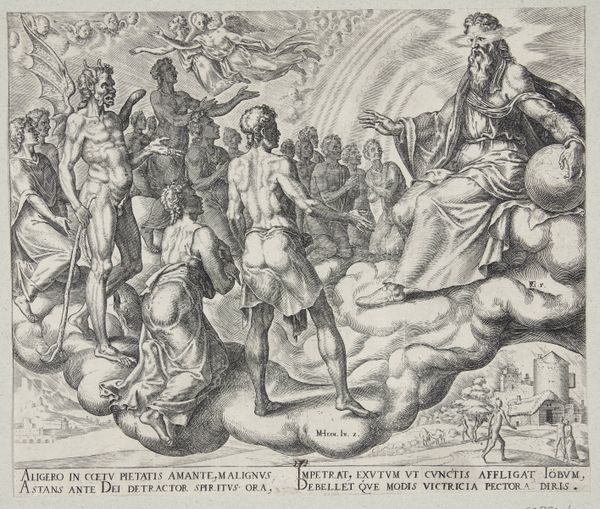

print, engraving

#

allegory

# print

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 194 mm (height) x 265 mm (width) (plademaal)

Curator: Philips Galle created this engraving, "The Triumph of Chastity," between 1563 and 1566. It's currently held at the Statens Museum for Kunst. What's your first reaction? Editor: It strikes me as strangely...restrained. For a "triumph," the overall feeling is surprisingly formal, almost cold. The composition, while intricate, seems meticulously planned and lacking in spontaneity. Curator: Well, let's consider the context. Galle was working within a well-established printmaking industry, one deeply shaped by commercial demands and workshop practices. This wasn't about pure artistic expression; it was a carefully produced object meant for a specific market. The engraving itself reflects a highly skilled labor process, turning design into reproducible image. Editor: Agreed, technically masterful, no question. Look at the precision of the lines, the detailed rendering of textures and drapery. But the allegorical subject matter feels very distant. Chastity personified on her elaborate chariot, unicorns pulling her, figures labeled "Scipio" and "Joseph"—it's all very contrived and artificial, based around symbols rather than emotions. Curator: Indeed. The choice of materials matters, though. The relative affordability of prints allowed these complex allegories to circulate widely. Disseminating concepts of morality and virtue through printmaking became a form of cultural production, one readily consumed by a rising merchant class keen on demonstrating its social sophistication and good taste. The production method dictated the reception. Editor: And I would add, examine the formal organization. Notice the dominance of vertical and horizontal lines. The temple on the left echoes the one further back; and each group of figures is framed in isolation, reducing overall energy. I'd say this enforces a hierarchical reading of power, not some celebration. Curator: It also reflects the influence of Mannerism, doesn’t it? The exaggerated poses, the artificiality, and complexity were popular among educated elite buyers. These elements signalled refinement and erudition, further reinforcing social distinctions through art ownership. Editor: So, in considering the formal properties alongside its production and reception, one can better understand that beyond simply seeing chastity triumph, that this composition acted as a mirror that reflected, confirmed, and celebrated a certain type of cultural refinement of the upper classes during the 16th century. Curator: Exactly, by examining both materiality and representation, we understand so much more.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.