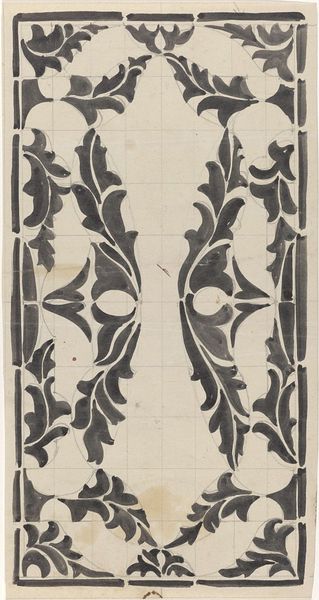

Dimensions: height 280 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

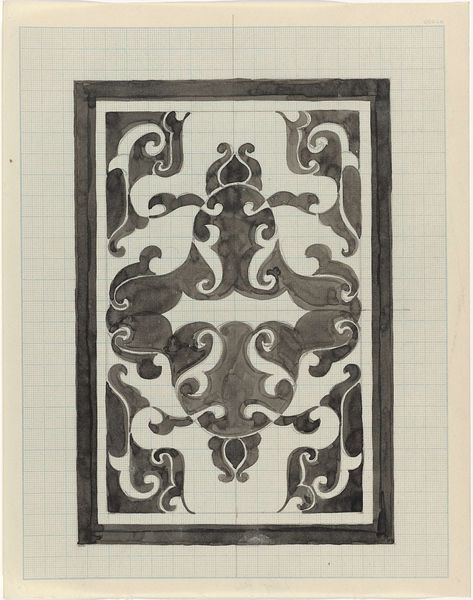

Editor: This is “Decoratief ontwerp met vissen” - or “Decorative design with fish” - a drawing in ink on paper, potentially from 1942, by Carel Adolph Lion Cachet. The composition has a rather symmetrical and balanced quality. It's striking how the fishes and shell motifs create a sort of all-over pattern. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It’s fascinating how Cachet uses these naturalistic motifs—the fish and shells—within a highly structured, geometric framework. Given the likely date of 1942, it's hard not to see this work through the lens of World War II and the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. Do you notice how the repetitive, almost militaristic, arrangement of these traditionally free-flowing organic forms creates a sense of constraint? Editor: That’s an interesting perspective. I hadn't considered the historical context. I was focusing more on the Art Nouveau aspects, the flowing lines… But I see what you mean. Curator: Consider that decorative arts during wartime often served purposes beyond mere aesthetics. In a time of immense social upheaval and oppression, artists frequently embed coded messages, acts of resistance, and symbolic hope within their work. Does knowing this influence your understanding of the image? Editor: It does! I can see the potential tension between the beauty of the individual motifs and the rigid structure they’re forced into. Maybe the artist is hinting at a struggle for freedom, a yearning for the natural world, in a time of confinement. Curator: Exactly! And thinking about the socio-political role of art invites these critical perspectives into conversation with traditional art-historical readings of the period, hopefully creating new forms of engagement with our collective histories. Editor: I now appreciate the work’s layers of meaning. It’s a beautiful decorative piece, yes, but it’s also a reflection of the artist’s lived experience and response to the climate of oppression. Curator: Absolutely. Seeing art as enmeshed in its cultural moment, rather than separate from it, allows us to interpret it as a historical text, and, I think, ultimately brings us closer to a shared sense of understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.