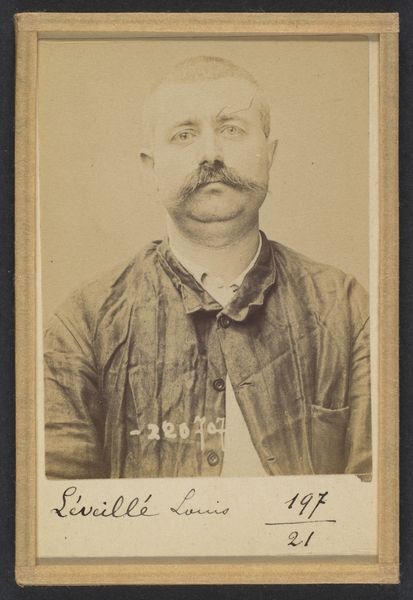

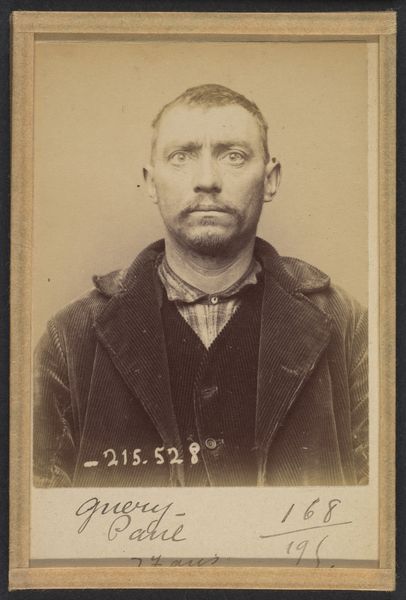

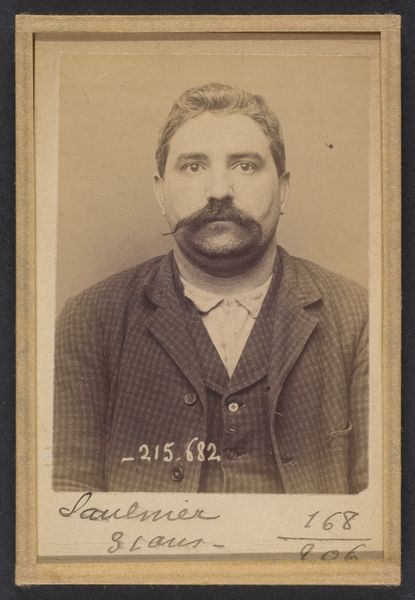

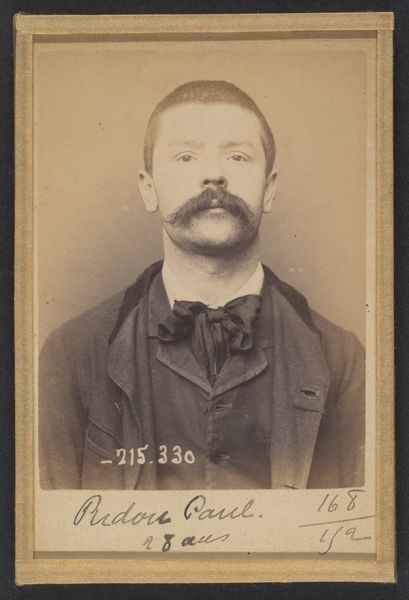

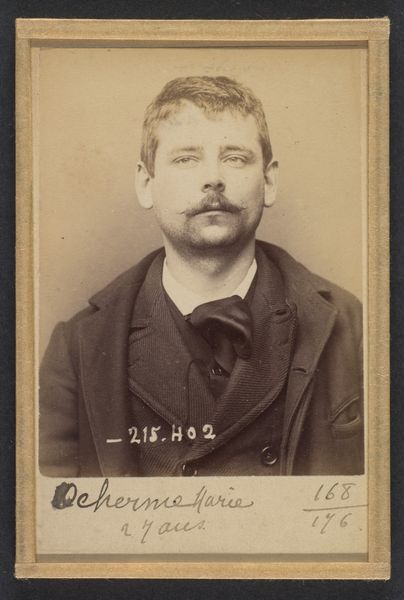

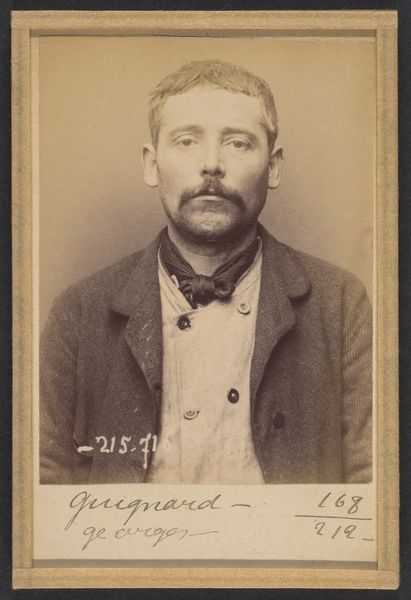

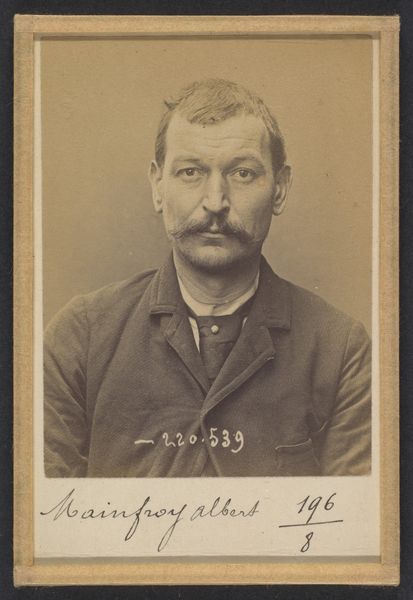

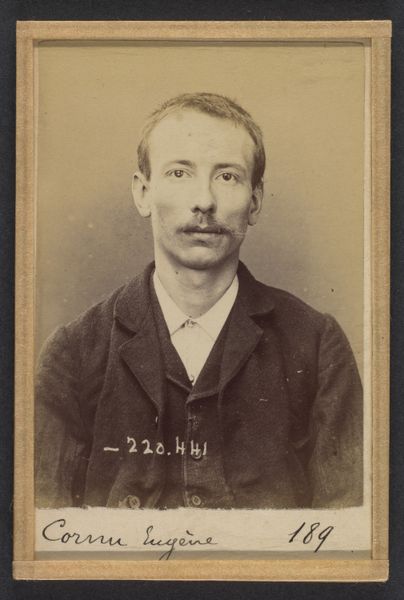

Reytinat. Jacques, François. 48 ans, né à Mouy (Oise). Colporteur. Anarchiste. 9/3/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a gelatin silver print from 1894 by Alphonse Bertillon, entitled "Reytinat. Jacques, François. 48 ans, né à Mouy (Oise). Colporteur. Anarchiste. 9/3/94." It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately, it feels stark. The sepia tone, the direct gaze. It's intimate, yet there's this sense of… alienation? It's like staring into a historical record of human fate. Curator: Indeed. Bertillon was a French police officer and biometrics researcher. He pioneered the use of photography for criminal identification. This is a mugshot, essentially. Editor: So it's an object lesson in the power of images. Think of all the artistic portraits meant to immortalize; this portrait is meant to categorize, control...yet there is a vulnerable human captured by it all. It brings forth strong emotions in its lack of ceremony. Curator: Precisely. Bertillon's method, "Bertillonage," involved detailed measurements, and photographs like these. It was considered scientific, objective policing. The caption details Jacques's occupation and political affiliation: "colporteur" – a peddler – and "anarchist," both labels carrying significant weight and prejudice in 1890s France. Editor: It is fascinating to contemplate the idea that Bertillon felt science removed biases, but now history reveals the opposite may be closer to the truth. Look how the information serves the image itself to bias the viewer. The sitter has a look of acceptance, though. Does he have something to hide, or nothing at all? It certainly sparks speculation about how this moment might be viewed when removed from the historical context and displayed at The Met. Curator: The photograph became a tool of social control. But your comment touches on the irony. Bertillon aimed for objective truth, but the categories themselves are socially constructed, fraught with assumptions. What is deemed criminal, who is watched? And, how does photographic representation influence public perception and institutional power? Editor: Right. As if fixing an identity, and one’s freedom to act, in silver. In some ways, photographs don't steal souls, as legend would have it, but preserve the moment they were stripped away by circumstance. Curator: Well said. It is these considerations, this intersection of individual, historical context, and representational technology, which makes it such a potent work of historical importance and aesthetic intrigue. Editor: Ultimately, it stands as a reminder that images have power, particularly when deployed as an agent for surveillance. I leave seeing this moment not just a preserved glimpse of a person and a time, but also one that asks, 'Who decides the portrait we get, and what biases may influence the truth of the rendering?'

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.