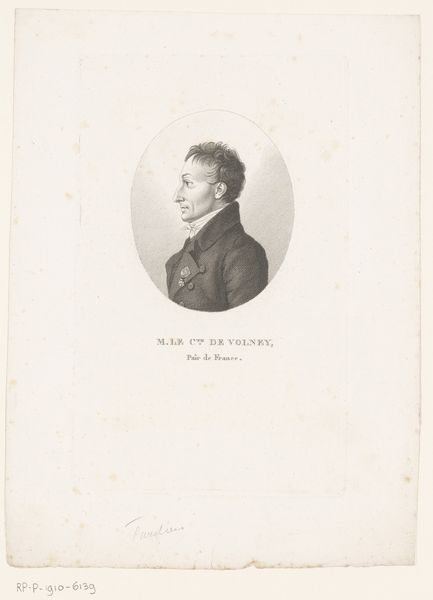

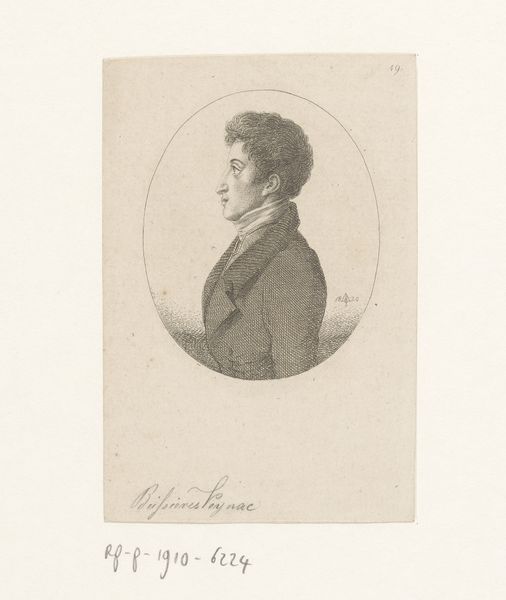

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 163 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

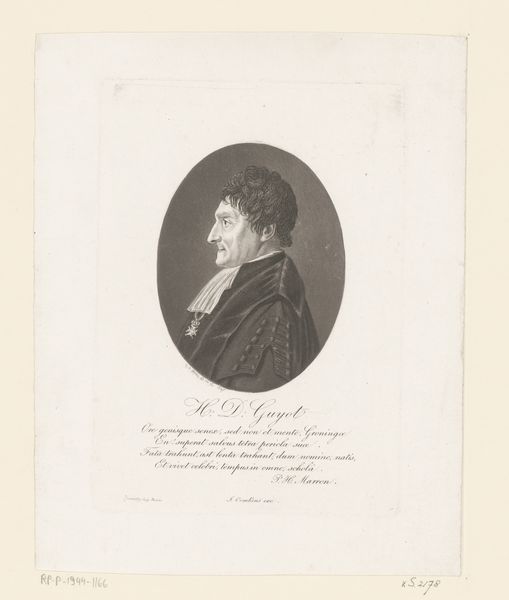

Curator: This is "Portret van Charles Henri Plantade," an engraving by Antoine Achille Bourgeois de la Richardière, created in 1806. Editor: There's a kind of severe elegance here. The precision of the line work coupled with the tight circular frame focuses all the attention on his profile and...well, there's something quite authoritarian about the upward thrust of his chin, isn't there? Curator: It is indeed a classical, almost stoic representation, placing Plantade within a lineage of respected figures of the era. Given the historical context, in the Neoclassical style that drew from ancient models to evoke ideals of order and civic virtue, portraits like these helped establish and maintain social hierarchies. Editor: Which is interesting considering that this isn't an oil painting meant for some palace, but an engraving. So it was a mode of representation that was reproducible and relatively more accessible, wasn't it? The print functions, then, as a way of democratizing portraiture...sort of? Curator: In a limited way, yes. The proliferation of engraved portraits meant likenesses could circulate more broadly than painted portraits allowed. And inscription mentions Plantade was a "Membre de la Réunion des Arts, Sciences, et l’Amitié", linking him to intellectual circles—that adds another layer, suggesting the work was produced for a network of educated, possibly politically engaged individuals. It speaks to an expanding public sphere, although access was still restricted to a particular social class. Editor: So even though the print medium could, potentially, democratize the distribution of images, in practice its use was still framed by these existing structures of privilege. And I’d add, visually, the lack of dynamic light, coupled with a clear, unemotional line speaks to the values of the Enlightenment—emphasizing reason, order and control, all read through the social mores of the time. Curator: A fair assessment. We should not ignore that "Portret van Charles Henri Plantade" served specific societal functions related to class and intellectual networks, solidifying reputations and celebrating certain values. Editor: Precisely. It's in appreciating this complexity that we get to view the portrait beyond just the historical figure and glimpse how systems of power and recognition played out two centuries ago.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.