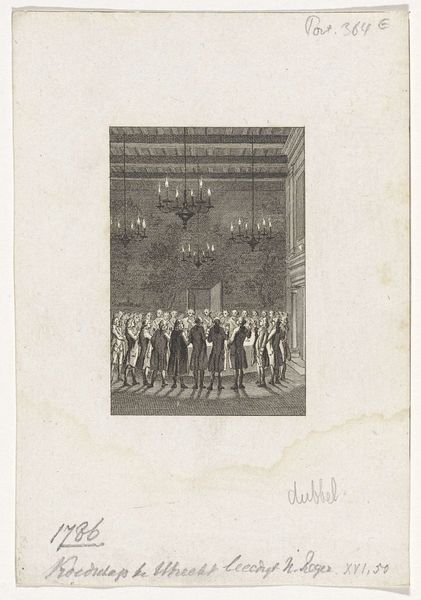

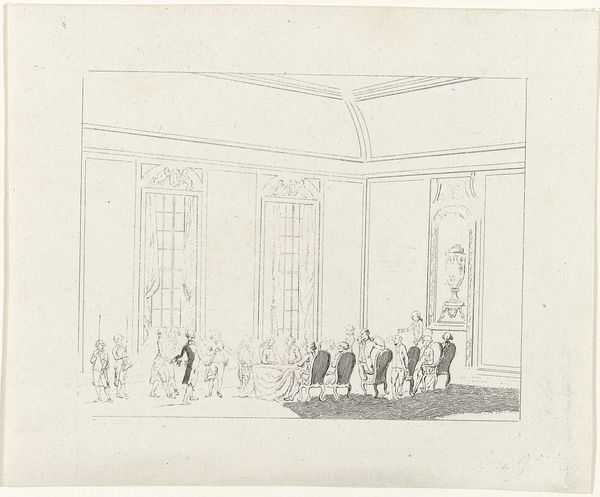

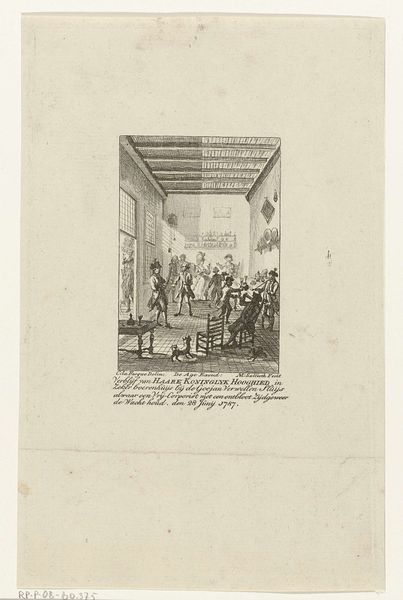

Willem V toegesproken in de vergadering van de Staten van Zeeland, 1786 1786

0:00

0:00

mathiasdesallieth

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

paper

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 225 mm, width 265 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This ink and engraving on paper by Mathias de Sallieth from 1786, titled "Willem V toegesproken in de vergadering van de Staten van Zeeland, 1786" captures a significant moment. The Rijksmuseum holds it now, offering us a peek into late 18th century Dutch politics. What are your initial impressions? Editor: Austere. My first reaction is to the starkness of the image. The fine lines, almost delicate, belie the serious subject matter depicted. The arrangement of figures is regimented but feels somehow detached. Curator: Yes, it reflects the prevailing Neoclassical style—emphasizing order and clarity, fitting for an official representation of a Stadtholder addressing the States of Zeeland. Consider the choice of engraving: a reproducible medium, ideal for disseminating this image widely, shaping public opinion about the House of Orange. Editor: It's fascinating how the artist used such simple materials – ink and paper – to convey such political weight. What strikes me is how this work enters the visual rhetoric around leadership. We see these individuals framed not merely by walls but by explicit images of naval power and mercantile success. These drawings within the drawing, what do they suggest? Curator: A very deliberate construct. The imagery underscores the naval power wielded by Zeeland and, by extension, Willem V, essential for trade and colonial ambitions. This points to a carefully orchestrated visual campaign to project authority amid growing political unrest at the time. Note, too, that the material itself is an agent of power—printmaking facilitated an explosion in the reach of visual rhetoric, changing consumption. Editor: So, beyond being a depiction, the work itself becomes an actor in the very political theater it portrays. Considering its context – growing unrest, shifting power dynamics – how was something like this actually received? Was it persuasive? Did it simply document an event, or was it designed to mold popular sentiment? Curator: Exactly! Understanding reception requires considering socio-political currents—patriot factions challenging the Orangists, demanding democratic reforms. An image like this could serve as Orangist propaganda, but its impact was undoubtedly complex. Perhaps reaffirming faith amongst supporters while stirring discontent among opponents, contributing, potentially, to revolutionary sentiment in its own right. Editor: It's an important reminder that art is never created nor viewed in a vacuum, the materials and display are intertwined. This makes me see past the official narrative; what begins as a record instead reveals fractures in political discourse that speak to much broader societal change. Curator: Agreed. Thinking about the material realities of its production and circulation—the networks it moved through, the hands that reproduced and consumed it—enables a deeper, more critical understanding of its place and purpose within the turbulent landscape of the late 18th century.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.