print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

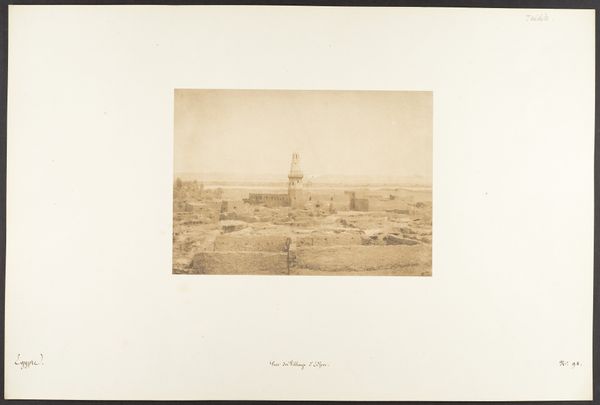

Dimensions: Image: 6 in. × 8 3/8 in. (15.3 × 21.3 cm) Mount: 12 5/16 × 18 11/16 in. (31.2 × 47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

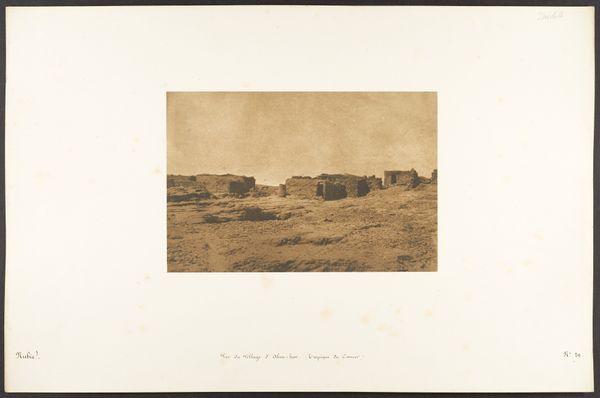

Curator: Sobering, isn't it? A gelatin-silver print from around 1850 by Maxime Du Camp entitled, "Vue du Village d'Herment" – a view of a village, taken in Egypt, a piece held here at The Met. What impressions do you have of this image? Editor: My first thought is, how desolate! A ruined settlement baking under a relentless sun. You can almost feel the heat radiating from the sepia tones. There’s a stillness, almost a mournfulness about it. Curator: And that’s interesting because this image appears amidst significant colonial ventures, an attempt to portray and document the region of Egypt for a Western audience, and to bring back to France, a tangible and palatable perspective. This intersects of course, with France's imperial goals. Editor: The image is a window into another time and a story about ruins, both in the sense of a place fallen to time but maybe too about dreams of empires past. That lone tree, like a weary sentinel, stands defiant. The composition—that wide, empty space—amplifies the feeling of solitude, abandonment. But, despite that melancholy, it’s incredibly striking! Curator: Absolutely, and beyond its aesthetic or emotional impact, we can't ignore the sociopolitical context. Photography, as a relatively new medium then, was being used to codify knowledge and exercise power. These early images helped shape Western perceptions, not always in ways that respected local culture or autonomy. They become records but also agents in complex historical processes. Editor: It's hard to separate that duality, isn't it? The artistic impulse to capture something real versus the machinery of power behind that capture. The ruins represent loss, but they are also now viewed through a very mediated perspective. That palm in the background suddenly becomes this quiet metaphor. Curator: It highlights photography's entangled relationship with progress and preservation, even its latent, unintended, role in shaping historical narratives. Editor: Yes, so it offers layers upon layers. I keep thinking about what's not shown... it begs us to imagine the people who lived here, their daily lives... their joys and sorrows. It is after all more than just a ruin to ponder and study. Curator: Indeed. Perhaps by acknowledging photography’s double edge, we find the potential to better contextualize the past with honesty. Editor: Here's to remembering that what’s pictured and what’s *not* can be equally illuminating!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.