Dimensions: 425 × 356 mm (image); 505 × 355 mm (plate); 527 × 379 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

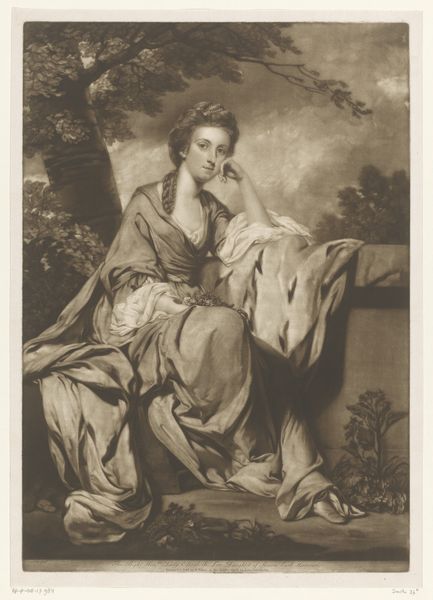

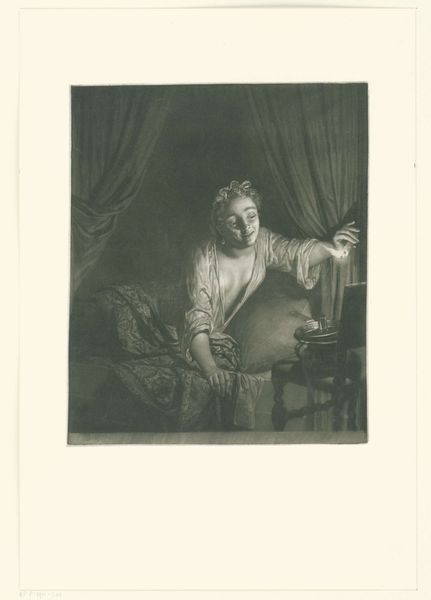

Curator: Welcome! We are standing before the print of "Lady Charles Spencer," crafted by William Dickinson in 1776. It resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: This is a powerful image. There’s a striking stillness; a woman pauses on horseback, perhaps after a long ride through a vast forest. The etching captures a moment of contemplation, don't you think? Curator: Precisely! The Rococo period was heavily dictated by societal conventions. What I find compelling here is Dickinson’s capture of aristocracy engaging with landscape. In reality, leisure pursuits like hunting or riding reinforced social standing and privilege. The very act of Dickinson creating such artwork shows its value to society. Editor: I wonder how Lady Spencer, in that moment, positioned herself in relation to the picturesque aesthetic, especially with Dickinson focusing on portraiture? Did she truly feel free, or was this simply another performance of her social role, with nature as a backdrop? Her identity certainly becomes interesting when gender enters into the discussion. Curator: I think it’s both, actually. The artistic production of her portrait provides insight to the complex dynamic. We see the engraver, the artist and then ultimately Lady Spencer as subject of scrutiny. Editor: Right, and Dickinson uses the engraving and etching techniques here to convey class and luxury, yet simultaneously making her somehow vulnerable. This is more apparent to modern-day viewers. Curator: The choice of medium adds another layer. Printmaking allowed for wider dissemination of aristocratic imagery; Lady Spencer’s image was meant to circulate, reinforcing a certain standard. Editor: It's difficult to look past that, for sure, but I find this print fascinating because it compels me to ask what freedom really looked like for women, historically, and who benefited from those representations. Curator: Absolutely. This artwork serves as a wonderful intersection to study 18th-century society through both gendered and political lens. Editor: It invites contemplation and reminds us that even leisure is not devoid of the intricacies of gender and power. Curator: And the production and accessibility of prints makes one wonder who truly owns her story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.