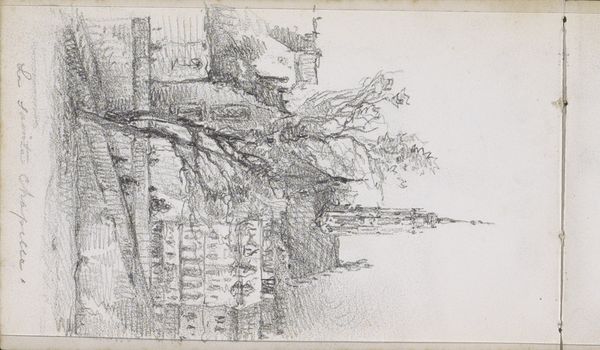

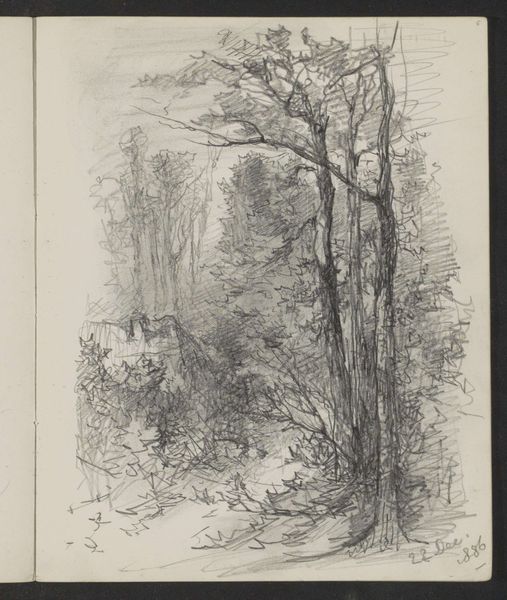

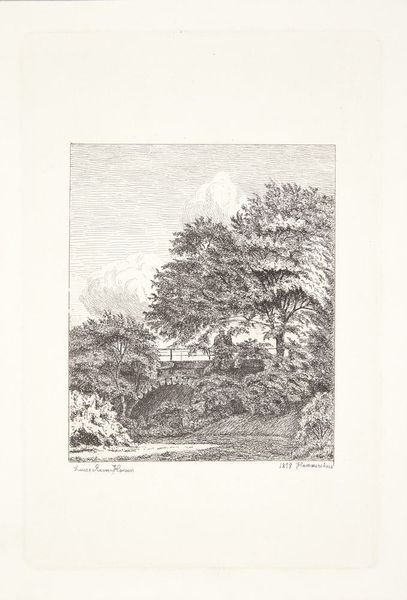

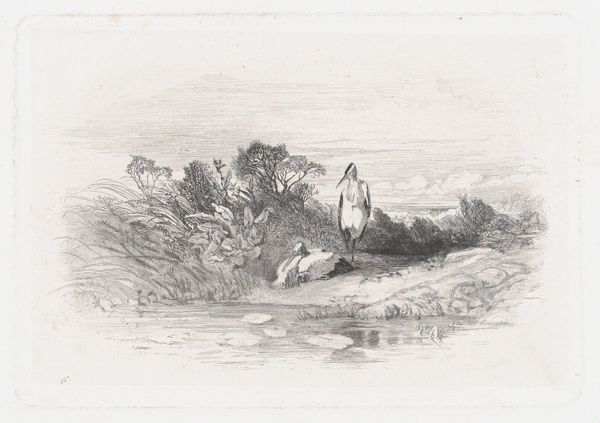

drawing, graphite

#

drawing

#

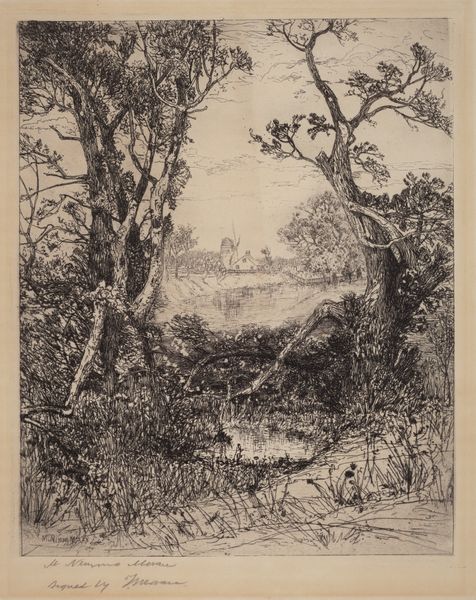

landscape

#

graphite

#

cityscape

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 16 5/8 x 12 1/2 in. (42.2 x 31.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

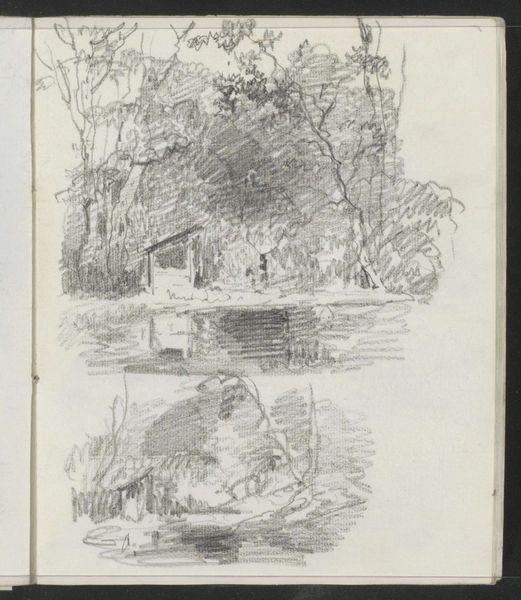

Curator: Looking at this drawing, my immediate feeling is one of slight unease. It's a pastoral scene, but the imposing structure looming behind it makes it feel…threatened? Editor: Indeed. The piece, titled "Central Park South," was created by Chuzo Tamotzu between 1935 and 1943, rendered in graphite. What you’re sensing might be a reflection of Tamotzu's personal and socio-political perspective, placing it within a broader historical context, as it engages with issues of urban development versus natural conservation. Curator: Exactly. It's as if nature is trying to reclaim the land, but the urban encroachment, a symbol of industrial and capitalist progress, overshadows it. Who gets to decide what landscapes are for, and at what cost? The tension he creates through the tonal gradations suggests it's an unstable negotiation. Editor: Right, that kind of struggle for space was palpable as urban planning and ideas around environmentalism were taking off. The politics of imagery come to the fore; Central Park was, after all, meticulously planned and crafted, made to appear 'natural.' What is a natural space, anyway? Curator: Yes, and by representing it like this, Tamotzu isn't just capturing a scene, he's interrogating that very construction of nature itself, particularly relative to whose benefit, and at whose cost. There’s an inherently intersectional perspective, one which layers identity with landscape. Editor: Well, and look where it's currently housed – the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Part of its cultural function then, and arguably still today, is in upholding specific narratives. Consider the impact of context on meaning! The placement further encourages considering our society's ongoing dialogue around progress and nature. Curator: Ultimately, "Central Park South" gives visual expression to tensions alive even now: the power dynamics that underlie decisions about what spaces are meant to be, and how they can be utilized in ways that serve many interests, without erasing others. Editor: Agreed, and that constant balancing act, made visible through a seemingly simple landscape, makes it incredibly impactful even generations later.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.