drawing, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

ink

#

group-portraits

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

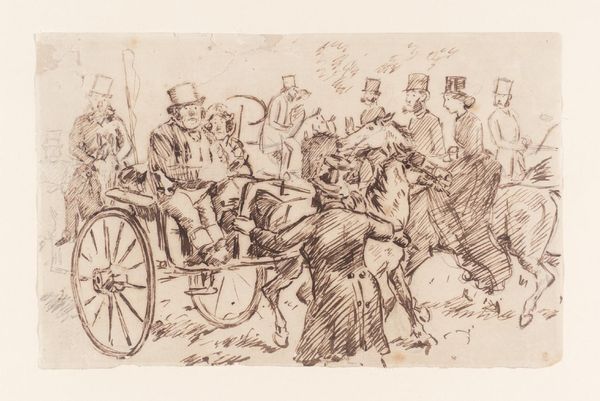

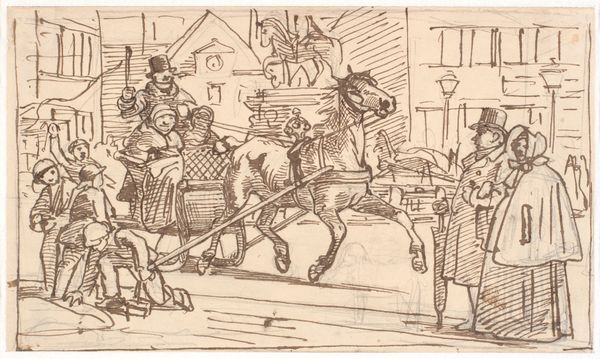

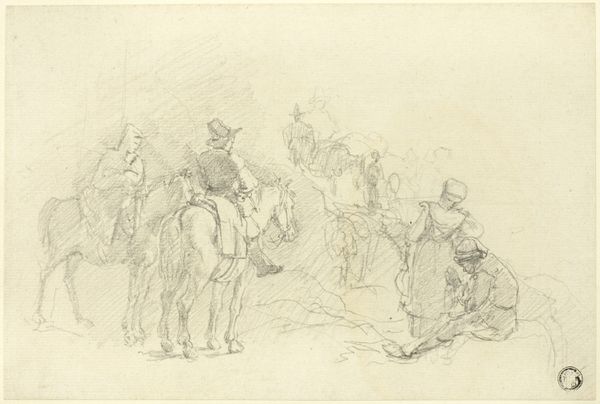

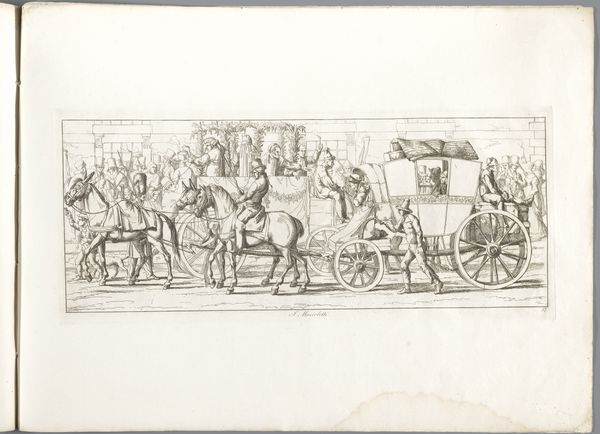

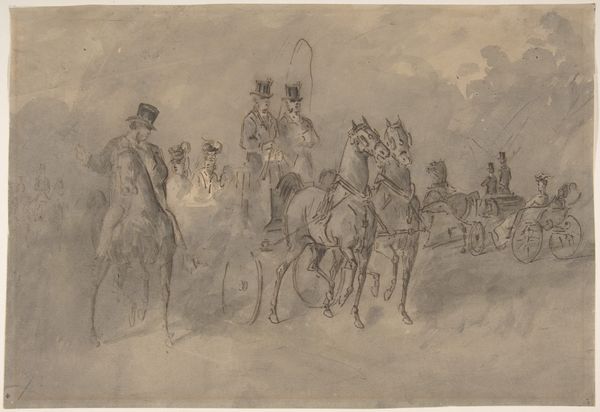

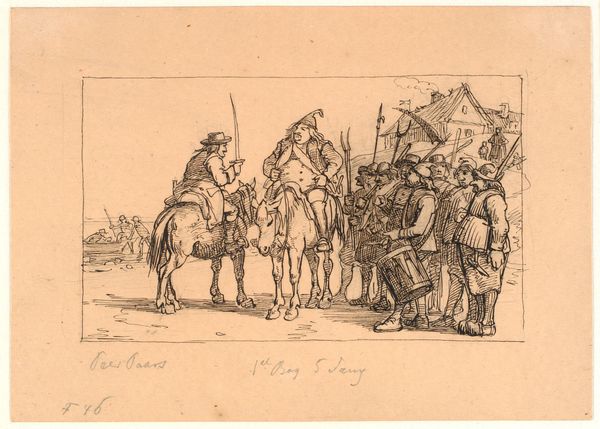

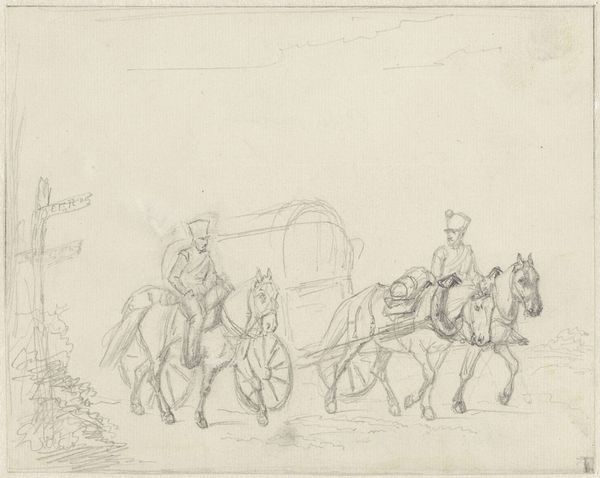

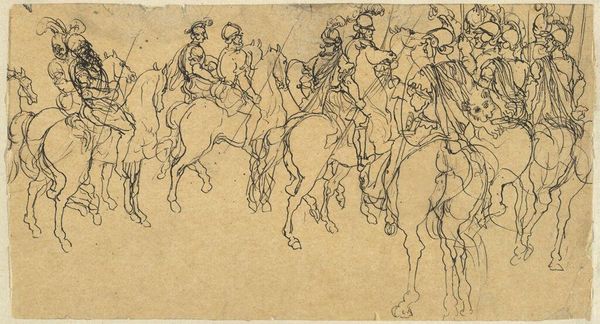

Curator: This pen and ink drawing by Sir John Everett Millais is titled "The Funeral of the Duke of Wellington," created in 1852. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Utter chaos, but a dignified chaos, if that makes sense. Like a controlled explosion of grief and respect rendered in frantic lines. You can almost hear the muffled drums and the somber clatter of hooves. Curator: Millais captured the sheer scale of the event. Wellington's funeral was a massive state affair, a public spectacle designed to solidify national identity and commemorate a military hero. The rapid sketches, one imagines, suggest it may have been executed *in situ*. Editor: There's such freedom in these lines! Not striving for perfect representation, but capturing movement and atmosphere. Those horses practically breathe on the page. Curator: It's fascinating how Millais balances this immediacy with the rigid hierarchies represented by the military procession. Look at how he delineates rank through variations in posture and dress. He uses these formal elements to emphasize the social order of Victorian society, solidifying Wellington's image. Editor: Order in visual anarchy... I also noticed the groupings in the lower part of the work, they appear like afterthoughts and seem a much less detailed summary of the event. Do you think this a personal study for a larger painting never fully realised, it feels fragmented, not complete? Curator: Possibly. Or perhaps it was meant to stand alone, an artist’s impression, rather than an official record. It reflects a shift away from purely academic history painting. He has included the details and impressions that grabbed his attention from what he saw that day in the street, details, a particular movement, an angle on the day’s event. Editor: A fascinating glimpse into a historical event filtered through an artist’s sensibility. You see both the weight of history and the artist’s fleeting encounter with it. Curator: Indeed. The drawing encapsulates both public mourning and personal observation in mid-nineteenth-century London. Editor: It makes one contemplate how much better historical insights we get through this kind of raw reaction than through posed portraits or pompous proclamations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.