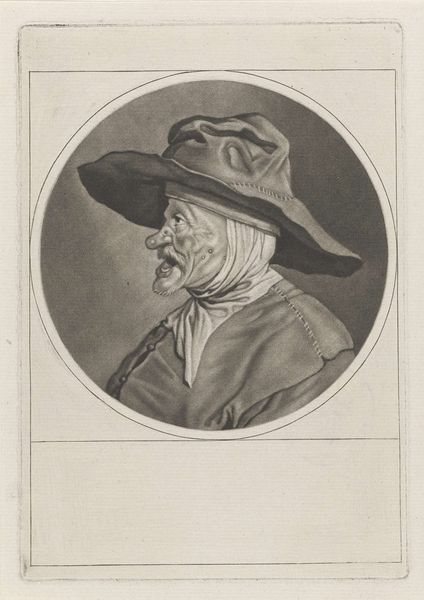

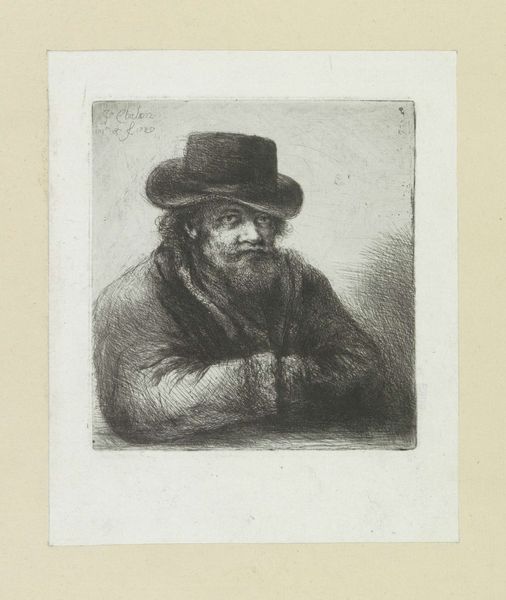

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, "Boerenkop," dating from between 1768 and 1796 and attributed to Pieter de Mare, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. The medium is engraving. What strikes you initially about it? Editor: Immediately, it feels incredibly intimate, almost a snapshot of a weathered character caught in a quiet moment. There's a kind of melancholic dignity to the subject, don’t you think? Curator: Absolutely. When considering prints like this, particularly engravings, I find it important to consider the labor involved in creating these images. Think about the skill required to render such detail, the artisan painstakingly incising lines into a metal plate, carefully building up tones to evoke depth and form. It makes the "Boerenkop," literally translated to 'Farmer's Head,' not merely an image, but a testament to human craft. Editor: And the very notion of "farmer’s head," elevates a specific social class, giving a voice, or at least a visual presence, to a group that was often marginalized or overlooked in traditional portraiture of the time. The choice of portraying a commoner like this is quite radical, positioning this subject within a broader discourse of representation. It prompts us to examine how ideas around identity were being explored through art in the 18th century. Curator: Precisely. The realism—although it's filtered through the engraver's artistic hand—allows a kind of visual connection to a particular social class. Prints had a social purpose. These weren't paintings, made for wealthy elites. Instead they are items mass produced for dissemination and sale to a broader segment of the population. We have to acknowledge printmaking’s democratizing role in art at the time. Editor: Yes, thinking about distribution is crucial. Who was seeing this image and how did it impact their perceptions of class and rural life? What preconceived notions did viewers bring to this representation? I'd even push this further by wondering how gender might be playing into this image. Is it the image of the patriach rural life that's represented here, for example? These are questions that should be raised and further examined. Curator: Indeed, food for thought. Seeing the engraving not just as a representation but a cog in the great machine of 18th century social thought, it enriches our viewing of it, don't you think? Editor: Absolutely. Placing "Boerenkop" within this expanded sociopolitical sphere, it becomes more resonant with ideas of representation, material labour, and the construction of identity. It is exciting to peel back the surface and view this image and time from many intersecting, meaningful vantage points.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.