Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

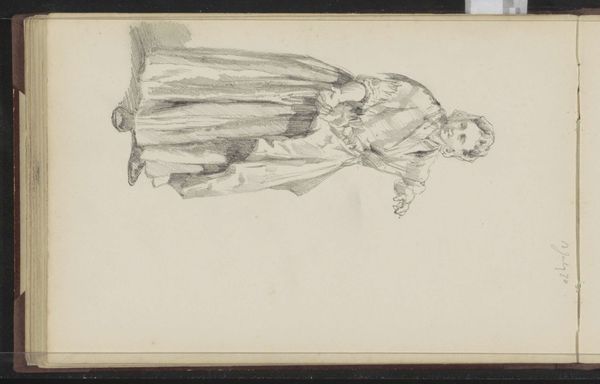

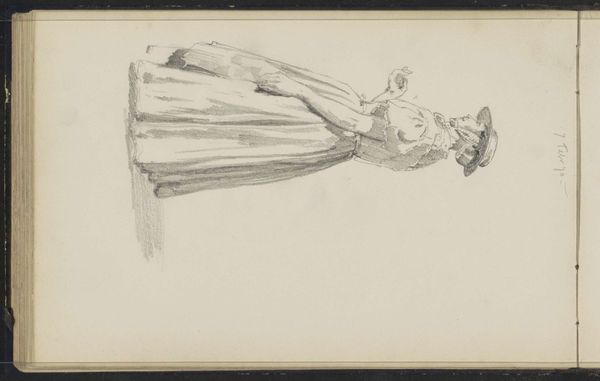

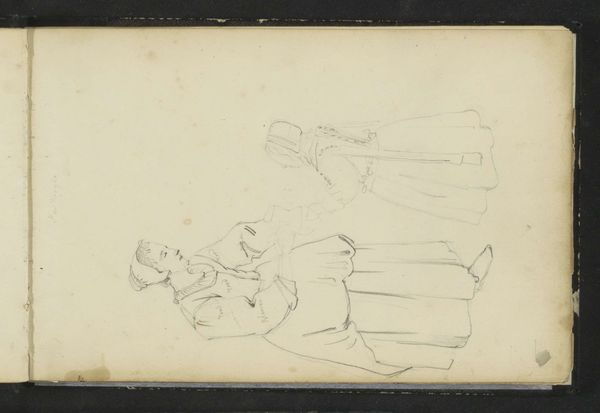

Editor: Here we have Cornelis Springer's "Women in Walcheren Costumes," dating from the late 1850s or early 1860s. It's a pencil drawing on paper. I'm struck by how immediate and almost ethnographic it feels. What can you tell me about this work? Curator: Well, consider the context. These pencil lines weren’t made in a vacuum. Springer, situated within the burgeoning Romanticism movement, would have been deeply concerned with portraying “authentic” Dutch life. What materials do we see being emphasized through rendering? The costumes, of course. These fabrics, the way they drape, the sheer volume, indicate skilled labor, production processes. The clothing isn't simply aesthetic; it’s a signifier of Walcheren's specific economy and social structure. Editor: So, you're saying that these costumes speak to something beyond just visual appeal? Curator: Precisely. Think about the means of acquiring, producing, and maintaining these garments. It signifies resources, skilled labor, and trade routes extending beyond this little island. We’re seeing, potentially, the beginning of an awareness about cultural preservation amid industrial change. Are we viewing a romanticized past that never actually existed? Editor: That’s fascinating. It’s no longer a simple sketch; it’s about labor and identity intertwined with material goods. Curator: Exactly. And by using simple pencil on paper – inexpensive and easily transportable – Springer democratizes the artistic process. Anyone can pick up a pencil and engage with their surroundings, document their own observations about the social fabric. How does that change our understanding of art itself? Editor: I see what you mean. I never would have thought to interpret a simple drawing in this way, examining not just what's represented, but how and why. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.