drawing, print, etching, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

fantasy-art

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

engraving

Dimensions: 149 mm (height) x 109 mm (width) (plademaal)

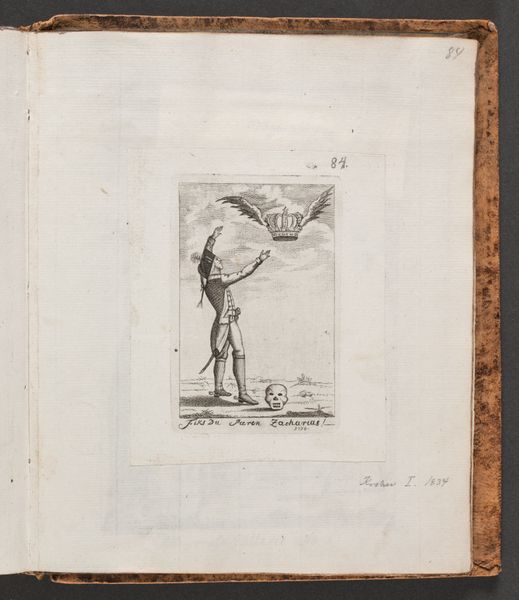

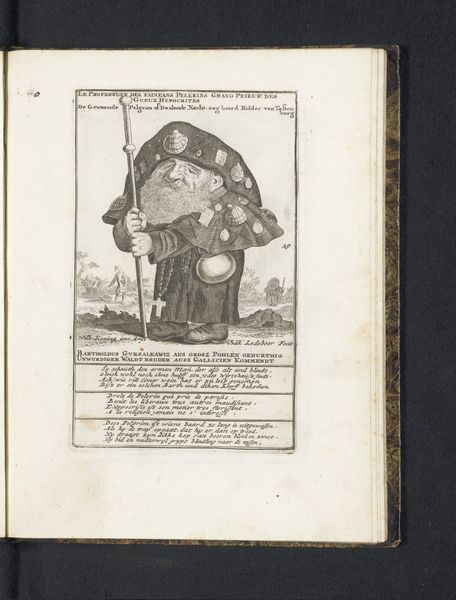

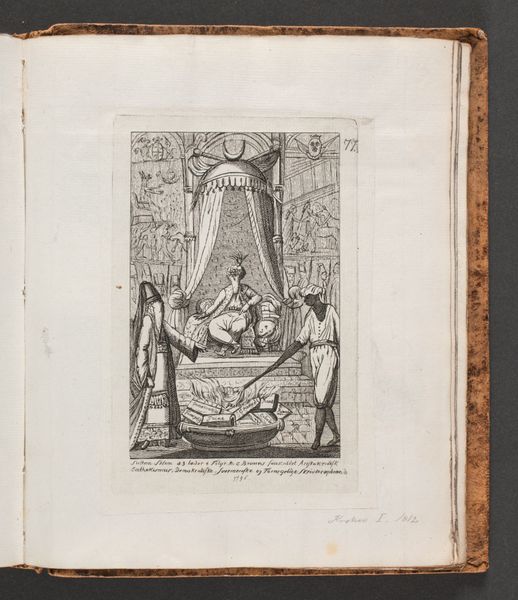

Curator: This unsettling image is an etching, engraving and drawing in ink on paper entitled "Fanden er sluppet ud af sit Castell," dating back to 1796. Editor: The mood strikes me as… spectral. It’s the stark contrast between the black ink and the pale paper, maybe, and the way everything's so meticulously rendered. And look at that gaunt figure; it’s unnerving, deeply uncanny. Curator: Indeed. The title, translated from Danish, means "The Devil is out of his Castell." It's an intriguing commentary, reflecting the socio-political anxieties of the late 18th century, when established orders were being questioned and overthrown throughout Europe and its colonies. What does that say about what the public saw, at the time, of those social movements? Editor: The figure's exaggerated form hints at a distortion of power. Notice the tiny person standing on its palm and controlling both sun and fleur-de-lis symbols – this power dynamic appears as a clear statement on societal hierarchies. It also pushes toward broader themes: colonization, cultural domination… What does it mean that it's coming out of his "Castell", or "castle", as we would say today? Curator: The "Castell" likely represents entrenched authority. By depicting the devil escaping its confines, the image could be seen as questioning the divine right of monarchs and the Church’s authority and, perhaps, pointing towards a break in old European ideals. The style fits squarely into the Romantic period’s focus on the irrational, the sublime, and the darker aspects of the human experience. Editor: The detail is stunning. Given that this is a reproduction in a book of images, the work could also represent democratization; perhaps to criticize social hierarchies in ways not immediately obvious to an authority looking to shut it down. What this image "means", both now and centuries ago, isn't necessarily its author's singular intent, or its popular interpretation, but what this image *does*, right? It can invite us to consider just how much has shifted in that balance of power, but more critically: what remains? Curator: Absolutely. Art is always a reflection of, and an intervention within, a specific historical and social moment. Looking at it allows us to not only engage with a piece of history, but, as you stated, to consider and even engage in some much-needed critical dialogues about our present. Editor: Precisely. There are far more historical reverberations and present connections in this drawing, and with artwork in general, than meet the eye.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.