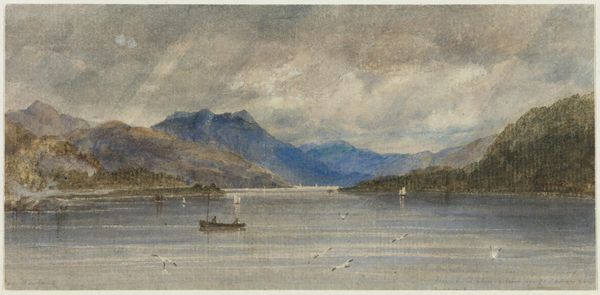

plein-air, watercolor

#

tree

#

plein-air

#

landscape

#

river

#

impressionist landscape

#

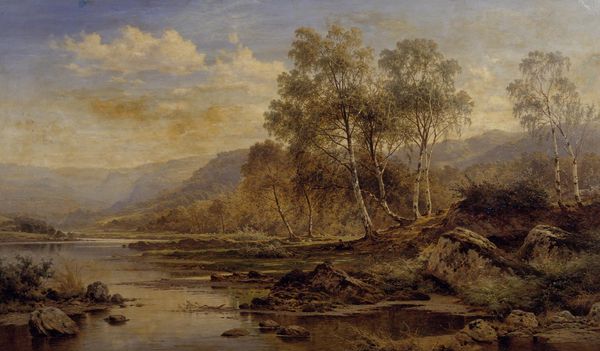

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

natural-landscape

#

water

#

watercolor

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

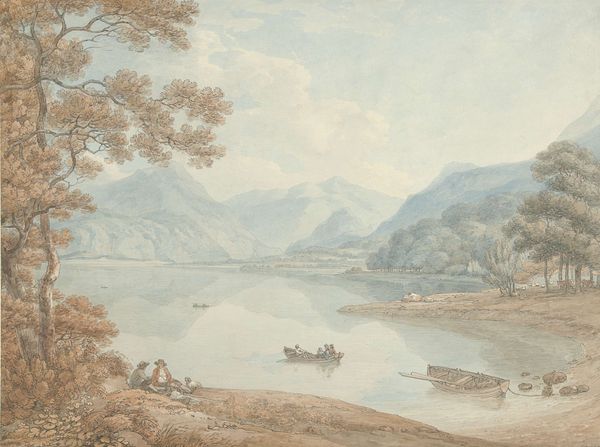

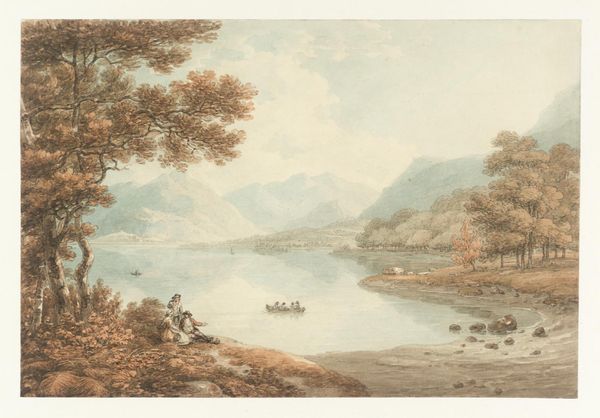

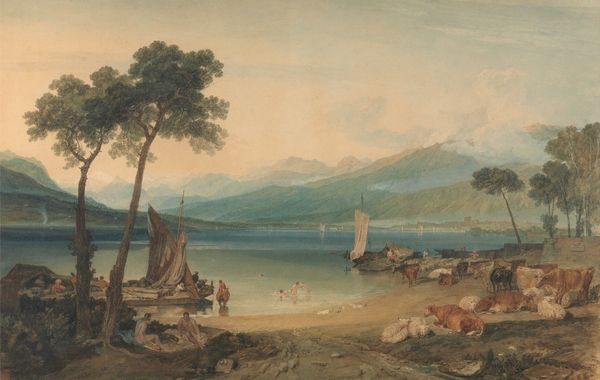

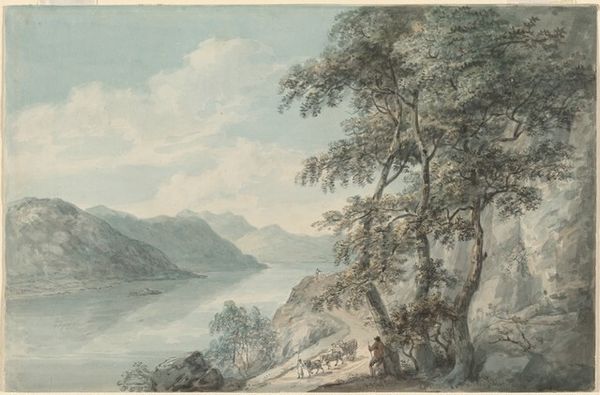

Curator: At first glance, I sense a palpable stillness and quiet observation—a window into another time and place. Editor: Indeed. We are looking at a watercolor titled "Copy of A. V. Copley Fielding's Loch Achray" made in 1835, originally attributed to the esteemed art critic John Ruskin. Its charm certainly lies in that sense of bygone peace. Curator: Right. Watercolor was a medium prized for its portability and the speed at which artists could work *en plein air*, especially by someone like Ruskin who would have valued sketching in the open air and making studies for his written work. What strikes me is the evident and immediate attention to natural form. How it is more of an act of studying the tonal contrasts on a rock rather than an assertion of landscape dominance. Editor: Absolutely, and there’s so much tied into that tradition. Ruskin, like other Romantic artists of this period, connects nature to ideas of freedom, perhaps even resistance to growing industrialisation. Here, the worker guides livestock near calm waters—he is a witness to nature. His labor in caring for animals creates his lived experience in a natural setting, outside the manufactured constraints of the city. Curator: Considering the labor of it brings in other contexts as well; who prepared the artist’s paints, who manufactured his brushes, or provided him with water, all materials that are drawn from the environment itself? How far back to we extend the notion of natural context and at which point do these details begin to impact our perception of Romanticism? Editor: These are important details because so much of landscape painting also had to do with land ownership. Visuals often left out elements of poverty. In Britain, there are a great number of landscapes commissioned by owners of enslaved plantations, where the great homes act as both signs of aesthetic appreciation for nature and active reminders of power, oppression, and control. Here though we see something different - rather than the ownership over the natural landscape being conveyed through the pastoral image, we are reminded about human interactions and responsibilities with the non-human world, but how do we perceive the ethics behind that sentiment given all we’ve uncovered about its art historical lineage? Curator: Right. While on the surface we see a harmonious scene, understanding it is really crucial to acknowledging its limitations, how its materiality, the paint on the paper, connects back to the socioeconomic factors that underpin that image's possibility, and even the ideology embedded within. Editor: Indeed, it compels us to ask tougher questions and resist simple interpretations. Curator: A constant excavation... and always unfinished!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.