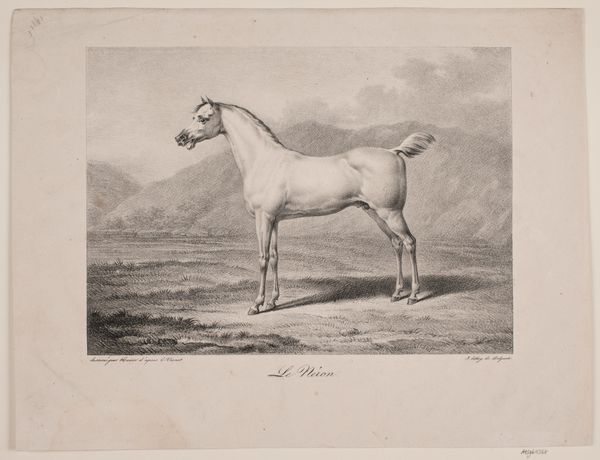

print, engraving

#

animal

# print

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

horse

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 407 mm, width 485 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have “Adonis, Favourite War Horse of King George III,” an engraving dating from 1825 to 1827 by Victor Adam, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's stunning, immediately evoking the Romantic era. There’s such a focus on idealizing the animal—the strong form, that graceful arch of the neck, almost ethereal set against the rough rocks. It speaks to a deep cultural investment in portraying power through animal representation. Curator: Indeed. What's interesting is placing this representation within its historical context. King George III reigned during a period of significant social and political upheaval. Think about the rise of revolutionary sentiments across Europe and how monarchy used symbolic displays, like portraits of esteemed animals, to reinforce their legitimacy. Editor: Absolutely. Consider also how this kind of image perpetuates notions of aristocratic dominance and class structure, literally placing the monarchy ‘above’ in terms of implied social and even, to a certain extent, 'natural' hierarchy. This depiction aestheticizes power in a very calculated way. I can't help but view it through the lens of critical race theory—who had the privilege to commission such portraits, and whose stories were omitted? Curator: Those are vital questions to ask. I'd add that these types of images were specifically made for dissemination to the wider public through print culture. This artwork can also tell us something about changing artistic conventions. Adam blends realism, evident in the horse’s musculature, with Romantic ideals of portraying emotion and drama. Editor: Exactly. And the engraving itself—the very choice of print medium—allowed for wider consumption, reinforcing social constructs, ideals of British Royalty, and its dominance far beyond the aristocratic elite who first saw the original horse, creating a complex narrative around monarchy, celebrity, and image-making. Curator: Looking at it through this critical perspective gives us so much to think about, how artwork functions both aesthetically and politically within its historical moment. Editor: Definitely, it compels me to question, resist, and rethink conventional assumptions about art’s role in reinforcing structures of power. It moves us beyond mere aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.