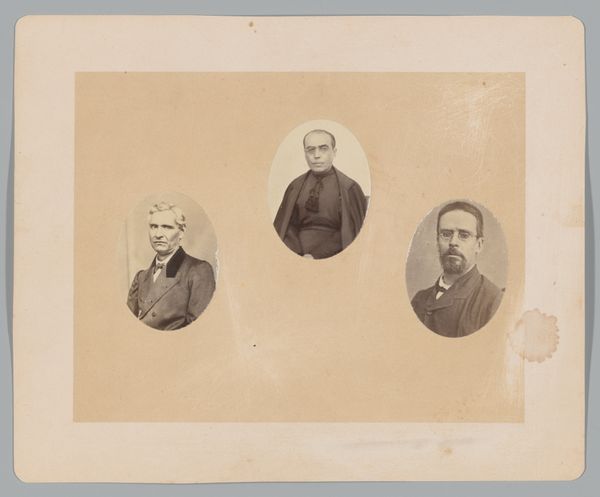

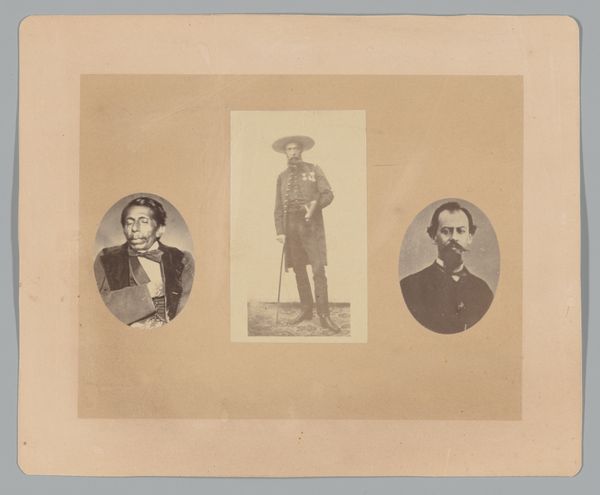

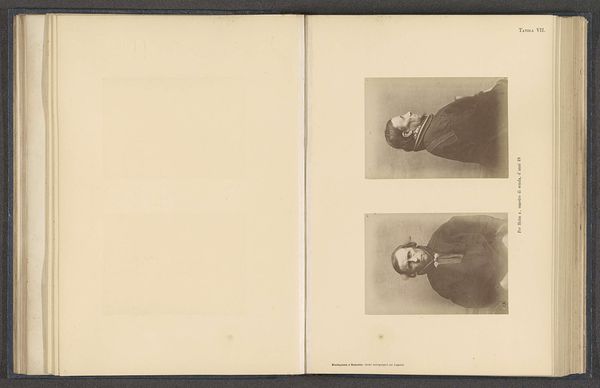

Drie portretten van J. L. C. Schroeder van der Kolk, Alfred de Vigny en Willem Vrolik 1842 - 1898

0:00

0:00

frederikaugustheyman

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

group-portraits

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 142 mm, width 225 mm, height 253 mm, width 340 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

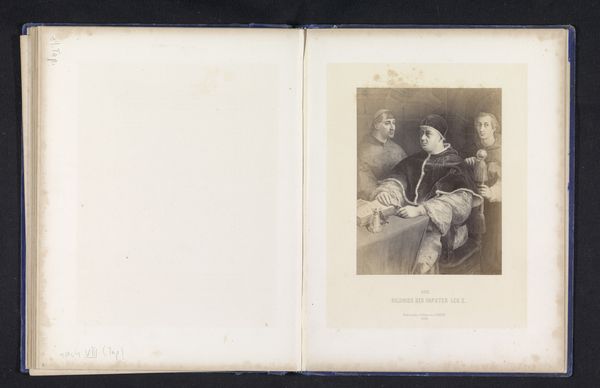

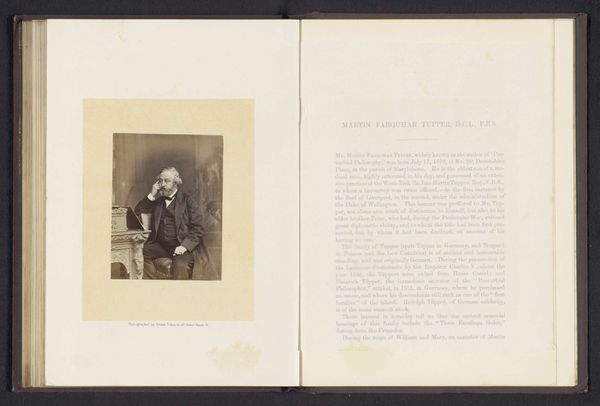

Editor: So, this is *Three Portraits of J. L. C. Schroeder van der Kolk, Alfred de Vigny and Willem Vrolik*, a pencil drawing from somewhere between 1842 and 1898, currently at the Rijksmuseum. It’s…interesting how starkly each portrait is presented, almost like specimens. What strikes you most about this piece? Curator: What interests me is less the aesthetic choice and more what the assembly of *these* specific men tells us. What did they represent that someone wanted to immortalize them together like this, and why in a drawing meant for printmaking and distribution? Van der Kolk was a prominent psychiatrist, Vigny a celebrated Romantic poet, and Vrolik a pioneer in anatomical pathology. How were those achievements intertwined, and for what public audience? Editor: So, you're seeing this as more of a statement about… scientific and artistic achievement? The piece really draws a sharp contrast in dress and pose: the stark, formal presentation of van der Kolk, against de Vigny’s romantic side profile… Curator: Exactly! Think about the context of 19th-century scientific and intellectual life. These were figures operating within specific, powerful institutions – universities, the literary salons, and medical societies. What narratives were circulating about the nature of man, the relationship between mind and body, science and art? A portrait like this helps us see how those ideas were visually constructed and disseminated to the public. Did de Vigny's romantic image reinforce some understanding of the artist figure in comparison to, say, a scholar or medical expert? Editor: So it becomes a sort of… propaganda almost? Illustrating a vision of the ideal intellectual, or professional? Curator: Propaganda may be too strong of a term, but yes, absolutely. It's about shaping public perception, visually defining these roles. I see how portraiture contributes to identity formation during this time. Think of its intended audience. Where might this print have been displayed? And for whom? These questions shed light on the public role of art and its entanglement with socio-political forces. Editor: That’s really changed how I see this. I was initially focused on the starkness of the style, but now I’m more interested in what these men *meant* at the time. Curator: Precisely! And that tension is itself telling: between aesthetic appreciation and critical understanding of art’s public role. It's about expanding how we ‘see’ the image beyond surface impressions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.