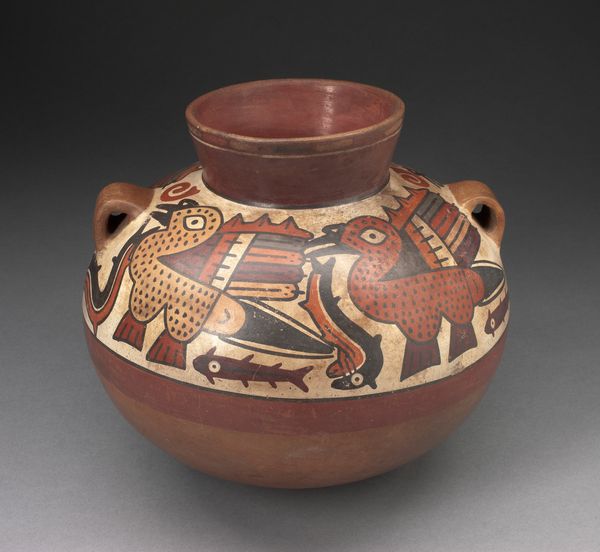

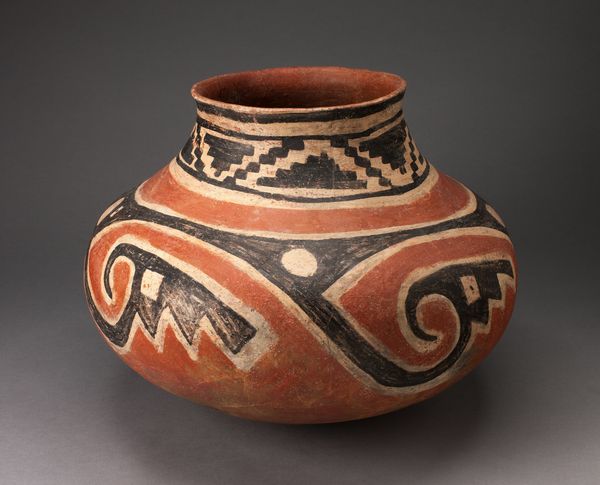

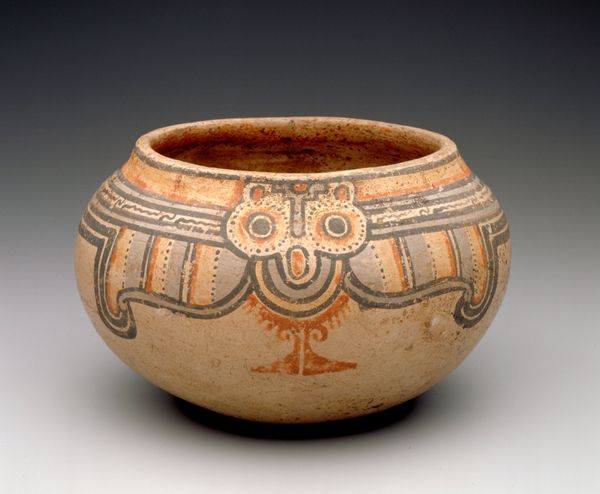

ceramic, earthenware

#

ceramic

#

earthenware

#

geometric

#

ceramic

#

earthenware

#

decorative-art

#

indigenous-americas

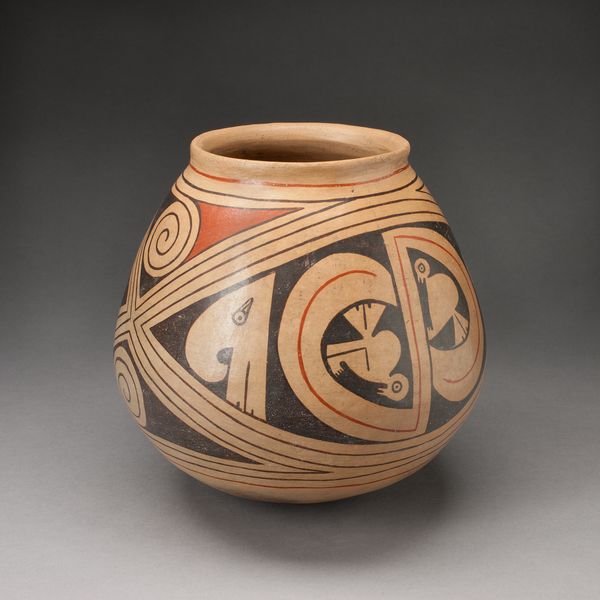

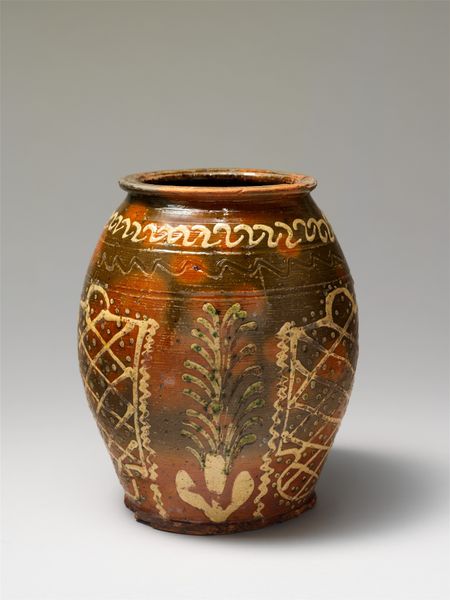

Dimensions: 10 1/2 x 13 1/2 in. (26.67 x 34.29 cm)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

Curator: Ah, the "Olla"! Isn’t it marvelous? Crafted around 1900-1910 by the talented Martina Vigil Montoya. Editor: My first impression? It feels very grounded, earthy... like holding the world in my hands. And the decoration seems to capture a playful dance with natural elements. Curator: It’s so wonderful you picked up on that interplay. Montoya utilizes earthenware—an ancient, humble medium, yet the geometric designs she's painted elevate it. She seems to breathe stories onto its surface. Editor: Those geometric forms almost pulse with symbolic potential, don't they? Notice how the repeated shapes create an engaging rhythm. Triangles, stars, abstracted flora... A real language in their arrangement. Curator: Absolutely! And if we consider the context, these ollas—vessels—were not just functional; they were ceremonial. Consider the hand that shaped this pot and the traditions which it emerged from. The patterns likely encode lineage, cosmology... Editor: It makes you consider how such functional forms carry profound conceptual weight. In some ways, that makes the pot itself a very interesting paradox; a utilitarian object, but its aesthetic intent complicates how we classify its purpose. I appreciate how the colors enhance this; those muted tones evoke the dry landscape, that burnt orange. Curator: You nailed it. Montoya likely gathered her pigments locally. From a formal standpoint, I like to reflect on the fact that indigenous North American pottery like this existed long before Clement Greenberg began pontificating. What can this pottery teach us about seeing? How does form relate to function? I find that this single vessel gives me more questions than answers. Editor: Questions, definitely! The interplay between cultural meaning and formal composition gives it an ineffable quality. There’s something to be said about these earthenware vessels carrying so much story while speaking their own visual language. Curator: Exactly! To really dive into the artistry of these "Ollas" means embarking on an exploration beyond just surface appearance; it opens our ears to listen to histories. Editor: I totally agree. This exploration definitely takes us further than what meets the eye and urges us to dig a little deeper to understand.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Pottery making at Po-woh-ge-oweenge (San Ildefonso Pueblo) was impacted in different ways than at Haaku (Acoma). When the Santa Fe Trail was opened in 1821, enamelware and metal containers became available, causing the production of pottery to decline. Even so, there still remained a few potters who were producing various types of pottery. Two of these potters were a husband and wife team named Martina and Florentino Montoya. Their signature innovation was the extension of the white slip over the entire surface, including the underbody and concave base. The Montoya's had close ties to the Kotyit (Cochiti Pueblo) and are credited with introducing the "Cochiti slip" to Po-woh-ge-oweenge. This slip can be quickly polished with a rag and was preferred over the native slip, which required tedious stone polishing.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.