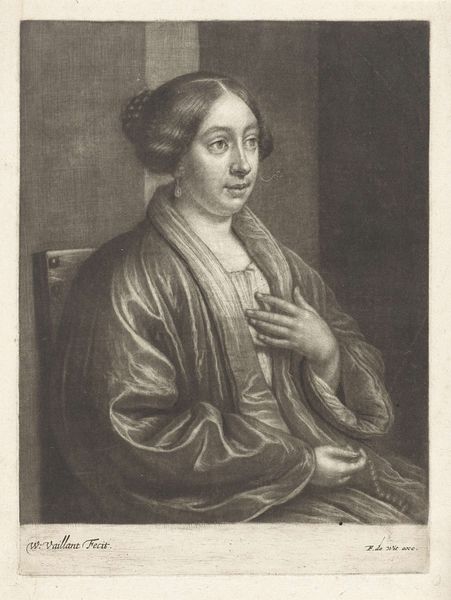

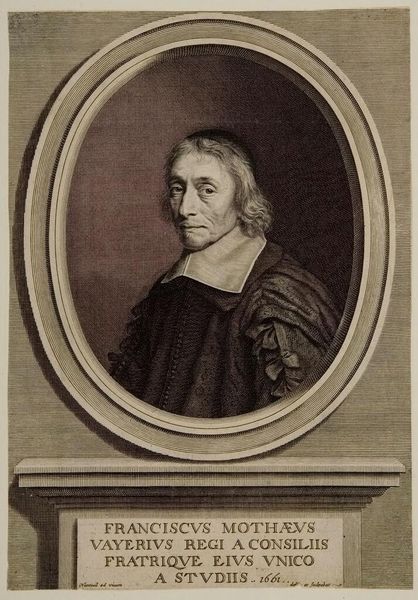

Dimensions: height 237 mm, width 170 mm, height 455 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Theodor Matham’s “Portrait of Girolama Giustiniana," likely engraved sometime between 1640 and 1950. It’s a Baroque-style print, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a certain austerity to the portrait. The oval frame and delicate lines create a feeling of formality, almost constraint. But Girolama's gaze has a captivating depth to it. Curator: It’s important to understand the cultural context. The Baroque period was characterized by displays of power, and in many portraits, nobility signaled prestige and rank through opulent dress. In Matham’s portrayal, Girolama wears dark fabrics and is without adornment. What statements are we making by stripping away such familiar emblems? Editor: Right. Let's unpack the iconography further. The veil, for instance. Does it primarily suggest mourning, or something about religious status? It also introduces an interesting shadow across her face, subtly obscuring her identity even as it purports to reveal it. What purpose did Matham ascribe to that visual rhetoric? Curator: And Matham's choice to position Girolama against a fairly neutral backdrop adds another layer of complexity, right? By minimizing distractions, it brings Girolama herself—her identity as a woman within a highly patriarchal society—into sharp focus. We can then read this work through the lens of gender and power structures of the time. Editor: Perhaps. To me, Matham wanted to represent what can never be depicted. Her spirit, the way her beauty remains as the engraving itself starts to wither with age. I feel like that is what Baroque art always wanted to symbolize: the everlasting spirit that prevails as everything falls to ruins. Curator: Ultimately, I think, the enduring power of Matham’s portrait resides in its ability to pose questions about female identity, both then and now. What does it mean to represent a woman, especially within such rigid cultural boundaries? Editor: Absolutely. It's the image’s timeless quality. Beyond just the Baroque era, we are witnessing how artists have been questioning our perceptions about what and who constitutes womanhood and how they are perceived, since forever.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.