print, woodcut, engraving

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

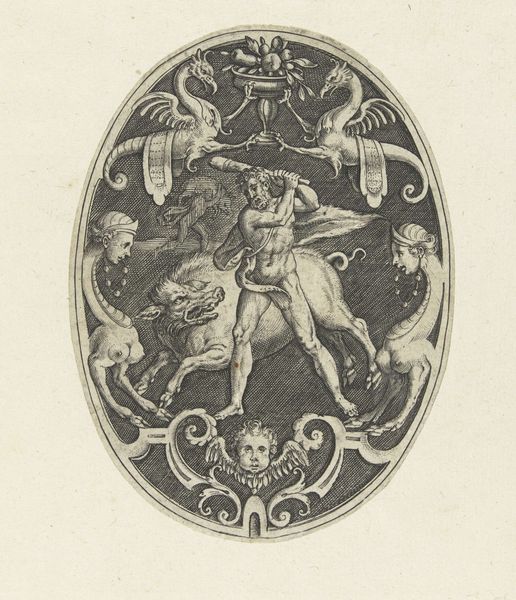

Curator: Here we have Hans Springinklee’s "H. Joris doodt de draak," or Saint George and the Dragon, created after 1515. The print showcases the legendary knight slaying a dragon. Editor: My first thought is, wow, it’s dense. The detail, achieved through what appears to be a woodcut or engraving, creates a lively but somewhat claustrophobic scene within the circular format. It feels almost frantic. Curator: Springinklee, active in Nuremberg, was deeply embedded in the social and religious contexts of the Northern Renaissance. Saint George was a hugely popular figure, embodying chivalry and faith in a time of great religious and social upheaval. The story served as a metaphor for good conquering evil, relevant then, and still resonant now. Editor: Exactly, and consider the labor invested here. Every line carefully etched to build the image— the horse's musculature, the dragon's scales, St. George's armor. Someone spent considerable time transferring design to block to final impression; it reflects values and social structures present when art’s craft met devotional demands. Curator: I see your point; there's an emphasis on meticulous detail. The symbolism, though, can be read on different levels. St. George wasn't just a religious icon; he also stood for social justice and defending the oppressed, perhaps reflecting growing societal anxieties surrounding power. How did such themes become fashionable through crafted objects. Editor: Because images like this, were broadly available, mass producible, in a way a painting could never be! And given this was printmaking, likely reproduced multiple times with different hands printing. We’re talking about social commentary embedded in production, reflecting beliefs within the community itself. I’d also suggest there's interplay here between what the artist creates with their labor vs what audiences were after regarding consumer desire within these mediums which could explain details appearing very crowded at certain sections . Curator: I hadn't thought about it that way. Examining both the historical context alongside its modes of making definitely offers a richer understanding of the work’s complexities. Thanks for spotlighting its material history! Editor: It highlights how we should think about consumption versus intention, especially if social narratives change but images can persist in new situations given access afforded though distribution/ labor behind original production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.