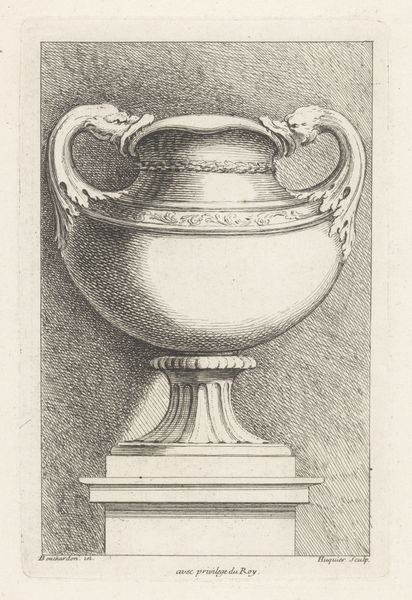

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

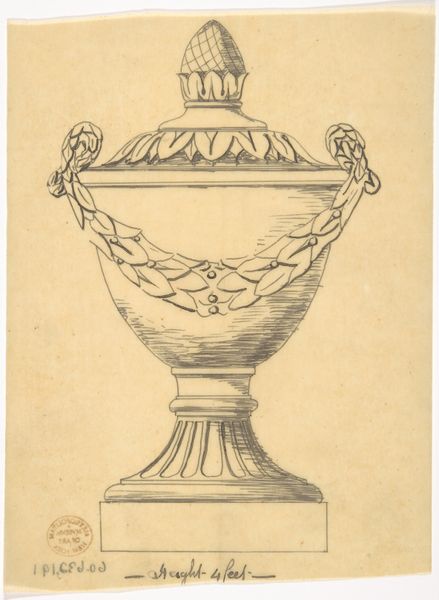

Curator: Standing before us is "Vaas met saterkoppen," or "Vase with Satyr Heads," an engraving from sometime between 1729 and 1737, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Gabriel Huquier made the print after a design by Edmé Bouchardon. Editor: It gives a palpable sense of density, doesn't it? The stark contrast and complex interplay of line work is almost dizzying in its ornamental flourishes. What I mean is, wow! So Baroque! Curator: Indeed. Look at the strategic placement of these stark, thin, consistent lines. Consider the vase's spiraling flutes and twisting rope-like base, which emphasize form and create dynamic visual tension. Even the satyr heads are geometrically perfect! The artist uses line weight variations to construct three-dimensional objects in just two dimensions. Editor: Let's not forget those satyr heads, a pretty common symbol throughout art history. Why incorporate them into this Rococo piece, besides decorative purposes? Could they reference ancient rites? Maybe they critique courtly values, presenting raw human passions—intoxication, sexuality—as they stand alongside refinement. This was a moment of immense wealth disparity, what statement is the artist trying to convey about indulgence? Curator: The function of satyrs here must be considered alongside the vase form. Huquier wasn't advocating some raucous subversion of aristocratic social norms, or decrying wealth disparity; he was crafting a desirable object. By focusing on beauty, harmony, balance and the mathematical properties of proportion, the viewer apprehends an ideal. I feel these ornate embellishments serve to elevate the vase as an object of refined beauty. Editor: Sure, but perhaps these contrasting themes underscore art’s simultaneous potential for the sacred and profane, reminding the aristocratic class, if that’s the intended consumer, of society's inherent contradictions at the very moment that class is acquiring, appreciating, consuming. It becomes an unspoken acknowledgment, etched into metal through intaglio, that these aesthetics and comforts exist within a larger ecosystem. It adds layers, and is anything BUT “just pretty.” Curator: Perhaps it's best to acknowledge that art can encompass a multifaceted appreciation, acknowledging form while reflecting a work’s possible socio-historic contexts. Editor: Precisely, it challenges us to consider how aesthetic sensibilities mirror and mold historical currents.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.