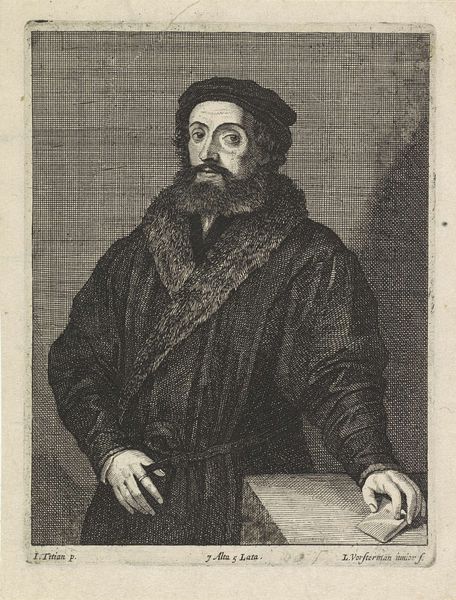

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait drawing

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 156 mm, width 122 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Philips Galle’s "Portret van Pietro Andrea Mattioli," an engraving created in 1572. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The stark contrasts in the print, created by thin, deliberate lines, gives it an almost austere feeling. It's certainly not a flattering image, and yet, it demands attention. Curator: Galle, working during the Italian Renaissance, often made prints after the work of other artists, circulating images widely. This portrait serves a didactic function, cementing Mattioli's status and scholarly influence. Mattioli was, after all, a very well-known physician and botanist of his time. Editor: Absolutely, but I’m more drawn to the depiction of the material itself – the luxurious fur draped around Mattioli’s shoulders. You can almost feel the weight and texture, suggesting affluence, position and power. This piece screams of craftsmanship, I can imagine how difficult it must be to get all of those nuances through an engraving process. Curator: Yes, those details signify Mattioli’s elevated place within the 16th century courtly society. This portrait also reflects the period's growing interest in representing individuals and celebrating human achievement. It makes me wonder about the patrons involved. What was Galle's role, exactly? Who was funding his studio? Editor: From my perspective, what strikes me most is the labor inherent in printmaking. The precise hand needed to translate those details of fur, clothing, and the individual's features... it is an intriguing tension between high art and laborious reproduction. Consider the copper plate; someone had to make it, prepare it, care for it... it is worth further exploration. Curator: It makes you consider how these images circulated – almost as an early form of visual networking among scholars. The circulation was tightly connected to political power in Italian Renaissance society, something we often overlook. Editor: Ultimately, this portrait really captures the tangible presence and social value tied to labor, materiality and status in 16th-century Italy. Curator: Indeed, it also invites a deep inquiry into how images shape historical memory and uphold the established social order.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.