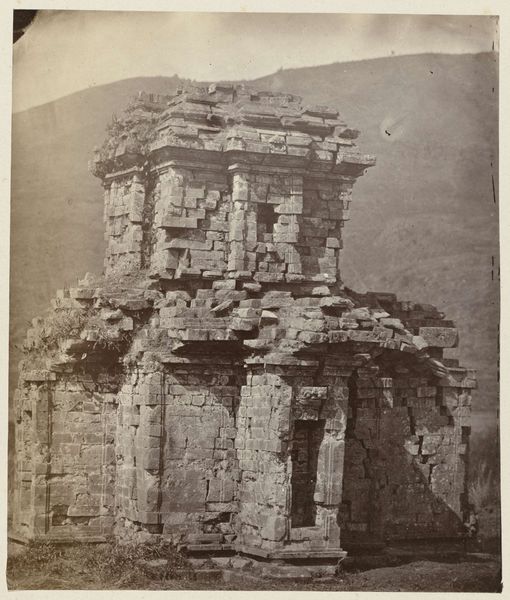

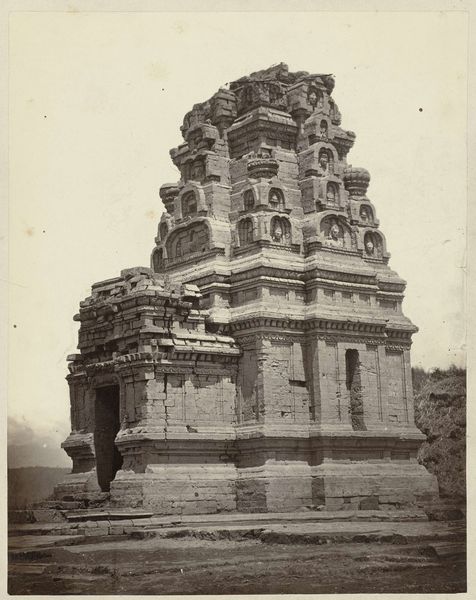

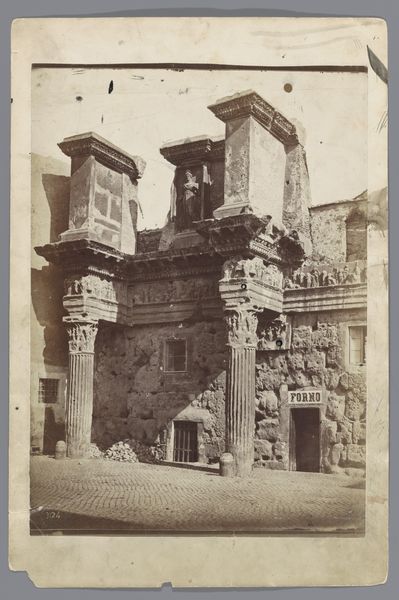

Candi Jabung, brick temple Jjabung, Probolinggo district, East Java province, 14th century. 1866

0:00

0:00

print, photography, architecture

#

excavation photography

#

medieval

# print

#

sculpture

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

photography

#

regionalism

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 340 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This intriguing photograph, taken around 1866 by Isidore Kinsbergen, captures Candi Jabung, a 14th-century brick temple in East Java. What’s your immediate reaction to this image? Editor: It feels incredibly solid, imposing even in its partially ruined state. You can sense the weight of the bricks and the structure's enduring presence despite time and apparent neglect. The ladder, haphazardly leaning against it, also makes me consider the labor required to build this temple and later attempt restoration. Curator: Indeed. The image encapsulates a tension between endurance and decay, prompting questions about how we engage with cultural heritage across vast spans of time and changing power structures. How do we negotiate the impact of colonialism in the excavation, documentation, and preservation of sites like Candi Jabung, and whose voices are prioritized in these narratives? Editor: Precisely. Look at the detail in the brickwork—that kind of craftsmanship speaks to immense skill and specialized labor. And of course, bricks are made of clay: literally of the earth, transformed through firing into something enduring. The process itself tells a story of technological knowledge and human ingenuity. Curator: And I can’t help but consider the original intention behind the temple’s construction. The sculptural details, even in their worn condition, suggest devotion, a specific iconography relating to local beliefs and power structures. This photograph provides valuable material evidence of East Java’s complex religious and political history, but interpreting it requires us to engage with postcolonial discourse that respects Southeast Asian perspectives on cultural identity. Editor: Absolutely. We have this image through a specific lens—Kinsbergen's colonial gaze, recording it at this moment of partial collapse. Now the contemporary work involved in archiving, documenting, and maintaining it requires different labor still. It really layers questions about preservation, commodification and what materials mean for society today. Curator: Ultimately, Kinsbergen’s photograph serves as a potent reminder that understanding art requires sensitivity to historical power dynamics, social contexts, and a nuanced recognition of cultural identity. Editor: And acknowledging the concrete processes—both physical and sociopolitical—involved in preserving our complex histories.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.